1. Dishwashers

I don’t have an M.F.A. I considered starting this essay, “I am a published writer, but I don’t have an M.F.A.,” but I thought that sounded more contentious, more chip-on-the-shoulderish than I actually feel about not having an M.F.A. I haven’t even ruled out the possibility of acquiring one, but at age 36, I have not earned a graduate degree.

How did this happen? This is a question I ask myself from time to time, usually when I am approaching a period of uncertainty in my writing career — or when the Internet throws the question in my face, as it tends to do, every few months. (More on that in moment.) Rarely does it come up in conversation. The only people who have ever asked me point blank are literary agents and other people’s parents. My own family has, if anything, discouraged me from going for an M.F.A. They don’t see the necessity of a graduate degree in fine arts. They are not alone in this feeling. I am often assured that “no one really needs an M.F.A.” But there are a lot of things in life that you don’t really need but which are awfully nice to have. Dishwashers, for example. Not having an M.F.A., I’ve decided, is like not having a dishwasher. Your dishes are as clean as anyone else’s, it just takes a lot longer.

When I started writing this essay, I envisioned a straightforward personal account about why I did not get an M.F.A. and what it has been like to learn to write fiction without that particular kind of institutional support. I thought I would give the reasons I avoided graduate school at different periods of my life (lack of confidence, lack of money, lack of time) and describe how I educated myself without it (night classes, writers’ residencies, and my beloved writers’ group). I thought my essay would show aspiring writers what a writing apprenticeship might look like outside of academia. And I thought that it would provide an interesting counterpoint to the narrative we so often hear, the one that seeks to professionalize creative writing by emphasizing credentials and career prospects. I also wanted to speak to the counter-narrative that aims to squash any delusions that an M.F.A. grad might have about the worth of his or her frivolous education.

It’s funny, even though I never applied to any M.F.A. programs, I want to defend them. I want them to exist in the world, and I want them to be sanctuaries of reading and writing and daydreaming. It irritates me when people try to tear down that vision with practical concerns, or by focusing on hierarchies of talent, or worst, by doing a cost-benefit analysis, as if everything can be easily broken down in terms of gain or loss. I suppose I chafe because I feel as if my life is being under-valued, my life in which I have held many jobs but have not climbed any ladders; my life in which my 20s disappeared between stints of writing bad fiction and reading great novels; my life in which I did not pay much attention to practical questions.

But as I began to look back on my 20s and early 30s — prime years for M.F.A.-seeking — I realized that my reasons were not as straightforward as I would like to believe. Beneath my sensible narrative is a deep anxiety around the very idea of getting an M.F.A.

It’s an anxiety with multiple strands. The first has to do with privilege. The second has to do with approval. And the third has to do with freedom.

2. Privilege

Every month or so, the Internet produces hand-wringing articles about the worth of creative writing degrees and/or the realistic job prospects for those seeking literary careers. Money is the measuring stick: Who gets paid to write? Who gets paid to teach? Does writing make money? Does teaching make money? Does publishing make money? Does it make enough money? Are there people who will do it for free? If there are people who will do it for free, doesn’t that devalue the work that others expect to be paid for?

I’ve been writing fiction for next to nothing for over 12 years. I’d like to say that I’m completely over the question of “What is the value of my life’s work within a capitalist framework?” But, you know, I’d also like to say that I’m over the question of “Is my body attractive according to Western beauty standards?” Some questions you can’t escape without becoming a full-time monk.

The Internet often operates as a mirror of one’s anxieties and last fall I had a novel under submission at several publishing houses. I was finding out what my fiction was worth and it was scary. I took a lot of articles personally. I got depressed just reading the subtitle of Cathy Day’s article here on The Millions, “Making Sense of Creative Writing’s Job Problem.” (Creative writing has a job problem? I always thought the thing that made creative writing so appealing was that it had nothing to do with getting a job.) The marketplace was also the frame of my colleague Nick Ripatrazone’s well-reported and sensible, “Practical Art: On Teaching The Business of Writing”. There was a warmth and calm to this essay that I admired, but I disagreed with the premise. Why teach the business of writing? Why emphasize to students something the world is going to force them to learn anyway?

Once I started reading these articles, I noticed they were everywhere. The New York Times Book Review questioned the value of M.F.A. programs by asking Can Writing Be Taught? (Consensus: yes). Over at The Atlantic, an article noted the increasing popularity of M.F.A. degrees, despite their increasing cost and poor job placement. This was characterized as “a mystery.” (Just think about that for a minute: an educational choice can be characterized as mysterious simply because it does not guarantee financial gain.) Financial journalist Felix Salmon warned young writers not to pursue careers in journalism if they hoped to have “a good chance at a well-paid middle-class lifestyle”. When a survey in the U.K. revealed that “author” is Britain’s most dreamed-of job, an author countered with a list: 14 Reasons Why You Shouldn’t Dream of Becoming a Full-Time Author. (Reason number one: “The money isn’t what you think it is.”) If aspiring writers weren’t sufficiently beaten down by the prospect of their pathetic lives outside of the well-paid middle-class, there was Ryan Boudinet’s much-discussed rant: Things I Can Say About M.F.A. Programs Now That I No Longer Teach In One. (Quick summary: now that Boudinet is not in the business of encouraging writers, he can discourage them with relish.)

This is but a sampling of the many articles, blog posts, book reviews, and round tables that question the value of writing programs. When I first started noticing them, I wasn’t sure if there were actually an unusual number of articles on the topic or if it only seemed so because I was seeking them out. But just a couple weeks ago, The New York Times published “Why Writers Love To Hate The M.F.A.”, an article that is pegged to the M.F.A. debate:

This is but a sampling of the many articles, blog posts, book reviews, and round tables that question the value of writing programs. When I first started noticing them, I wasn’t sure if there were actually an unusual number of articles on the topic or if it only seemed so because I was seeking them out. But just a couple weeks ago, The New York Times published “Why Writers Love To Hate The M.F.A.”, an article that is pegged to the M.F.A. debate:

A graduate writing degree, unsurprisingly, turns out a lot of opinionated writing. Sample manifestoes from blogs and chat rooms: “Why you should hate the creative writing establishment (…as if you needed any more reasons)” and “14 Reasons (Not) to Get an M.F.A. in Creative Writing (and Two Reasons It Might Actually Be Worth It).” In scholarly circles, the boom and its implications have been a subject of heated debate since at least 2009, with the publication of Mark McGurl’s The Program Era: Postwar Fiction and the Rise of Creative Writing. In it, Dr. McGurl, a Stanford English professor, describes the M.F.A. as the single biggest influence on American literature since World War II, noting that most serious writers since then have come out of graduate-school incubators.

The Times attempts to address both sides of the do-or-don’t debate, but leans toward don’t, ending with a quote from an aspiring novelist who is looking for a job. He is characterized as someone with “no illusions” about the feasibility of a writing career, but the article refers several times to the supposed out-sized ambitions and/or fantasies of aspiring fiction writers. Almost every article you read about M.F.A. programs will mention these delusions of grandeur, but in my experience, apprentice writers have the opposite problem. They’re an anxious bunch, with little confidence in their work. They feel that nothing they write will ever be good enough. They sit at their desks and wonder if deep down, they really are delusional. They interrogate themselves as harshly as the world does.

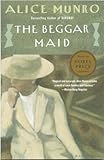

There’s a collection of short stories by Alice Munro titled, Who Do You Think You Are? (This is actually the Canadian title; in the U.S. the book was published as The Beggar Maid because publishers were not sure that American readers would fully appreciate the shaming implied by the question.) The stories concern Rose, a gifted young woman from a small village who aspires to an intellectual, cosmopolitan life, the kind of life that is usually reserved for young men of a higher social class. It’s one of Munro’s recurring themes, and the story of Munro’s own ambition. Nobel Laureate Munro does not hold an M.F.A., in part because M.F.A. programs were not as prevalent when she was coming of age, but mainly because she was a woman from a blue-collar background. The world had no expectation for her beyond marriage and children — an expectation she obliged in her early 20s, then defied by writing while her children napped.

There’s a collection of short stories by Alice Munro titled, Who Do You Think You Are? (This is actually the Canadian title; in the U.S. the book was published as The Beggar Maid because publishers were not sure that American readers would fully appreciate the shaming implied by the question.) The stories concern Rose, a gifted young woman from a small village who aspires to an intellectual, cosmopolitan life, the kind of life that is usually reserved for young men of a higher social class. It’s one of Munro’s recurring themes, and the story of Munro’s own ambition. Nobel Laureate Munro does not hold an M.F.A., in part because M.F.A. programs were not as prevalent when she was coming of age, but mainly because she was a woman from a blue-collar background. The world had no expectation for her beyond marriage and children — an expectation she obliged in her early 20s, then defied by writing while her children napped.

Who Do You Think You Are? To me, that’s the question that lurks beneath all these M.F.A. articles. So many of them remark upon the proliferation of creative graduate degrees, always noting the cost and time, the debt that so many students are likely to accrue. There is often a tone of annoyance. Who do these students think they are, racking up all that debt? Who do they think they are, taking such risks? Don’t they know their place? Don’t they know that getting an M.F.A. is a privilege?

Sometime in my mid-20s, when I was most seriously considering graduate school, I decided I wasn’t privileged enough to do it. I just didn’t see myself as someone who could afford to leave a salaried job for two or three years. Maybe it’s more honest to say that I wasn’t comfortable taking on that privilege. This is a discomfort that Elif Batuman exposed in her fiery 2010 essay, “Get A Real Degree,” which argues, among other things, that M.F.A. programs are secretly ashamed of the privilege associated with literary writing, i.e. “the anxiety that literature might not be real work.” As a result of this anxiety, writing workshops spend too much time trying “to recast writing as a workmanlike, perhaps even working-class skill, as opposed to something every no-good dilettante already knows how to do.” Batuman thinks this is ridiculous: “Pretending that literary production is a non-elite activity is both pointless and disingenuous.”

Eighty years earlier, Virginia Woolf told a room of female undergraduates basically the same thing when she said: “A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction.” In the same lecture, Woolf also described the world’s “notorious indifference” toward creative writing:

[The world] does not ask people to write poems and novels and histories; it does not need them. It does not care whether Flaubert finds the right word or whether Carlyle scrupulously verifies this or that fact. Naturally, it will not pay for what it does not want.

Woolf lays out the impractical nature of creative writing more sharply than any of today’s wet-blanket advice-givers. And yet she is much less cynical. By observing that what all great female writers had in common was a middle-class upbringing, she wants to liberate women, to let them know that the reason the world is full of male writers has little to do with talent or desire or willpower, and everything to do with how much time and money is accorded to them.

For a lot of writers, getting an M.F.A. is a way of getting Woolf’s room — and, if they are lucky, some money too, in the form of a scholarship or stipend. Those who don’t receive financial aid have to pay for the privilege. When I was younger, the idea of paying for the time and space to write really bothered me. I thought becoming a writer would mean more to me if I got there “on my own.” At my most cynical, I saw M.F.A. degrees as something people got to legitimize their desire to write — something to temporarily gain status, or worse, to please their worried parents. What I didn’t understand when I was younger was that there’s nothing wrong with this need for legitimacy, especially if it alleviates anxiety and allows one to write. (And we all know that people have paid a lot more and done a lot stupider things to alleviate status anxiety.) Nor did I realize how much I had internalized certain status anxieties. Mixed in with my guilt over my privilege was the question of whether or not my writing ability was even deserving of special attention; I worried people would think I was ridiculous for lavishing so much money and time on my negligible talent. I think that’s why I get so annoyed by articles (and, let’s be honest, comments on articles) that decry the value of M.F.A.s; they remind me of my inner good girl, the as-of-yet invulnerable phantom who wants every life choice to be approved of by others.

3. Approval

A big reason I never went back to school is that I worried that my good-girl impulses would take over in a school setting, and that my need for approval from teachers and peers would subsume the playful, secret, and defiant impulses that led me to write in the first place.

Like all children, I made up stories before I could read. Learning to write down the stories in my head was a revelation: they seemed real in a way that made me feel powerful. Even as I realized that writing was an approved activity in the eyes of teachers and parents, it was something I mostly did on my own time, outside of school, away from the prying eyes of grown-ups. I wrote for fun when I was child, and later I wrote to understand the world and my place in it. I have no idea when I decided I would one day try to write books, but in high school the idea was firmly in place. It just seemed like something I could do if I put my mind to it. I did not think of it as a career. I did not think of anything as a career when I was in high school. That was part of my youth and part of my privilege.

In college, I met people who thought of everything as a career. And, after college, when I moved to New York, I met people who thought of everything — even their personal lives — as a potential source of income. As much as I love the overall level of ambition of New Yorkers, the constant talk of what things are worth, in terms of marketability, is mostly stifling. For several years, I made tiny little handmade books out of old magazines and fast food wrappers and old photographs, but I stopped after a while, because whenever I showed them to people I was asked if I had ever tried to sell them and when I said no, they were just for fun — that is, a way of enjoying my creativity in the simplest, most childlike way — I was met with a confused, sometimes condescending gaze.

It bothers me that I stopped making those little books. I’m not sure why I stopped. I think I got the sense that if they didn’t make money or, barring that, fit into a “career trajectory,” they were a waste of time. And I didn’t want to waste anyone’s time. Or maybe: I didn’t want people to think I was wasting mine. That’s what I mean by my “good-girl” impulses. Bound up in these good-girl impulses, there is also a desire to be good, and to not spend my time on pointless amateur art projects when I could be helping others or, at the very least, making enough money to ensure that I will not require help from others.

Getting an M.F.A. has always felt like both a good-girl choice and a bad-girl choice. It’s the good girl choice because it imposes order, at least temporarily, on the unruly apprenticeship that every writer must complete. It’s the bad girl choice because it’s expensive and unnecessary. It’s the good-girl choice because it would have credentialed me for teaching. It’s the bad-girl choice because it wouldn’t have credentialed me for anything but teaching. It’s the good girl choice because it would have returned me to the school setting. It’s the bad girl choice because it would have taken me out of the world, away from the needs of others.

I believe every female writer has to contend with her inner good girl. Woolf called her “The Angel in the House.” She was the model of congenial femininity, an inner voice that stifled Woolf’s early days of writing:

She was intensely sympathetic. She was immensely charming. She was utterly unselfish. She excelled in the difficult arts of family life. She sacrificed herself daily. If there was chicken, she took the leg; if there was a draught she sat in it — in short she was so constituted that she never had a mind or a wish of her own, but preferred to sympathize always with the minds and wishes of others.

Woolf found the voice of the Angel so seductive that she had to permanently silence her: “Had I not killed her she would have killed me. She would have plucked the heart out of my writing.”

Sometimes I think that not getting an M.F.A. was my way of killing the Angel in the House. It was an easy way to rebel and, in a strange way, it gave me confidence. As much as I complained about the time my jobs took from writing, it felt good to support myself. I could feel pride in finding my own structure and routine outside of school and away from the voices of peers, who might unwittingly sound a lot like the chiding good girl within. Above all, I could write without seeking approval. For me, that was a kind of freedom.

4. Freedom

In his 2010 Paris Review interview, Jonathan Franzen was asked if he had ever considered getting M.F.A. when he was starting out:

Franzen: I got married instead to a tough reader with great taste. We had our own little round-the-clock M.F.A. program. This phase of our marriage went on for about six years, which is three times longer than the usual program. Plus, we didn’t have to deal with all the stupid responses to writing that workshops generate.

We did actually apply to some programs one year, in hopes of getting a university to support us financially, and we were both accepted at Brown. But the money Brown offered wasn’t good enough. In hindsight, I’m glad I didn’t go, because it might have smoothed some kinks out of the work that were better not smoothed out. As a journalist, I’m always striving to become more professional, but as a fiction writer I’d rather remain an amateur.

Interviewer: Did you devise another kind of program for yourselves? Did you go to readings?

Franzen: No, we didn’t want to be around other writers. In some semiconscious way, we recognized that we weren’t good yet, and we needed to protect ourselves from depressing exposure to people who’d already gotten to be good.

When I first read this interview, the idea of being an “amateur” fiction writer became a touchstone for me, because I thought I knew what Franzen meant. I thought he was referring to a kind of writing that was free, unfettered by expectation or obligation, and most importantly, not tied to employment.

Rereading the interview, I am struck by Franzen’s wariness. By not getting an M.F.A., his writing retained its “kinks;” his writing was “better not smoothed out.” I think here, Franzen is alluding to the great lit-crit bogeyman, M.F.A. Fiction. We all think we know an M.F.A. Fiction when we read it. It’s elegant and distilled and very cleanly written; there’s little urgency in the narrative or the language; it doesn’t seem to come from the writer’s heart and mind, instead it’s written from ego — a desire for a career, or maybe just a desire to avoid criticism by writing something unimpeachable. They’re what one of the women in my writing group calls “polite lady novels.” They’ve been around forever except in other eras we just called them boring books and didn’t feel the need to devalue an entire generation of teachers and writers.

And yet, there is a strain of fussiness in workshops, of talking about writing as if it’s something that can only be done in a certain way with a certain precision by a certain kind of special, talented person, when in fact writing is something that everyone learns to do as a child and many can learn to do quite well. Writing is democratic. This is something I have always felt, intuitively, but I wouldn’t have thought to describe it that way until I heard Jamaica Kincaid speak at a Q&A a couple years ago. The writer Ian Frazier, one of Kincaid’s oldest friends, moderated the discussion, and he asked Kincaid to elaborate on something she’d said to him when they were teaching together:

Frazier: One evening we were sitting around talking with people and we were talking about writing and you said, “writing is not an art” and I thought, Writing is not an art? And you said, no, it’s not like painting, it’s not sculpture, it’s not architecture, it’s not music, it’s not an art. You said, “it’s deeper than that.” Can you explain that? Because I wrote that down. I thought, Writing is not an art? Part of the point was that it can’t be taught, but another point was that it was something that everybody does — that speech is something everybody does.

Kincaid: Yes, everyone can do it. There are things that people who are involved in it like to make precious. And um, exclusive. And I suppose I say things like that because someone like me is not, uh, there’s no reason, there’s no example for me to follow to be a writer and I don’t want it to be exclusive and special and I want me to always be able to participate in it.

The phrase “writing is not an art” reminded me of Franzen’s amateur ideal. Perhaps the main reason I avoided graduate school was that I was afraid of being paralyzed by self-consciousness. Like Franzen, I worried about trying to compete with people who were better writers, or just plain more sophisticated. I was afraid of feeling like I wasn’t good enough, and I was afraid that feeling would spoil the naïve pleasure I took in making up stories. In retrospect, I don’t think a couple years of workshops could have spoiled something so deeply rooted and, you know, I might have learned something, too. But I understand why I felt such self-protective instincts. Writing is the one area of my life I have always felt is my own terrain, separate from anyone’s expectations about whom I should be and what I should think.

I think a lot of people feel this way about writing, that it’s a free and open space, that anyone can do it, and that’s why the elitism of M.F.A. degrees bugs the hell out of people. For some writers, getting an M.F.A. is simply not an option, for financial reasons or because they are occupied in some other way, e.g. full-time employment or caregiving. The more standard the degree becomes, or at least, the more it is perceived as standard, something a writer needs in order to be published, the more privileged creative writing becomes. From this perspective, I can see why people are grossed out by the rapid growth of M.F.A. programs. At the same time, the M.F.A. system has the potential to be a lot more meritocratic than the publishing world, simply because anyone can apply; you don’t need an agent or an introduction. The question shouldn’t be whether or not getting an M.F.A. is a worthwhile for those privileged enough to agonize over the cost. Instead we should ask: how can we better support people who want to write?

Support isn’t only about money. (Although more academic funding would certainly help a lot of writers.) Support is about making people feel as if their voices are important, as if it’s worthwhile for them to take the time to seriously engage with literature, to add their own stories, essays, dramas, poems, and novels to the conversation that’s been going on for hundreds of years and is thus far dominated by white men.

The literary world’s overwhelming white-maleness is well known and now, thanks to VIDA, well-documented. Things are changing, but not fast enough, and whenever I read an article that attempts to give a dose of “reality” by reminding would-be writers that what they want to do is really, really hard, in addition to being financially unsustainable, I hear condescension and defensiveness. Compare the “practical” advice of your typical M.F.A.-bashing article to the guidance that Kincaid gave, off-the-cuff, at her Q&A:

I was saying to some kids the other night, that among the things I find writing is, is it’s very dangerous. Sometimes you unexpectedly might be called upon to die for it and you should be able to say this is something I must say and know that after you say it, you will lose your head. And if you don’t feel that way, then you shouldn’t do it. I really do think that. It would be better to be dead than not to be able to write what it is I want to say.

Often as a writer, a certain kind of writer, you do feel people would like you to stop it, and in a way sort of kill you for writing this difficult thing, or for saying these unpleasant things, these things they call unpleasant, but I think you must just as some point, you know, you uh — hmmm, I have to be very careful — I’m willing to have my head cut off for saying something but on the other hand I don’t want to hurt anyone’s feelings. But yeah, uh…if that was all writing was about, well, I’d rather have just kept to the thing that I was consigned to be, which was a servant in somebody’s house, that was what I was meant to be, but I thought, this is the self that I want, the self you see before you is not the self that someone wanted me to be, it’s something that I made, and I made it happen through writing.

To me, the most significant part of this speech is the pause when Kincaid searches for words and then says, somewhat vaguely, if that’s all writing was about... There, I think the meager “all” she’s referring is not only a sense of decorum, but the sense of writing as a job in the world. If writing were just about making a living, about writing the words that will please other people and bring in a paycheck, she wouldn’t do it; it wouldn’t be enough for her. And maybe that’s what a lot of these cautionary articles mean to say: don’t try to make your living by writing. Try to make a life.

5. A Long-Winded Justification

I began this essay shortly after submitting a final draft of a novel to my agent, but then faltered because I feared it was too motivated by my fear of failure. There was also a part of me that thought that if my book didn’t sell, I would just be writing a long-winded justification of my stupid life choices.

Well, my novel did sell, but I still worry that this is just a long-winded justification of my stupid life choices. I would never recommend for anyone to live my life the way I’ve lived it and yet, the older I get, the fewer regrets I have. That’s maybe the central paradox of maturity.

There’s no one way to become a writer or to measure the success of a writer. That’s a good, even beautiful thing, but I’ll be the first to admit that it’s a situation that generates a lot of mixed feelings: uncertainty, regret, loneliness, and a whole family of selfs: self-pity, self-loathing, self-involvement, self-aggrandizement. I’m pretty sure writers are most tempted to give advice in the midst of mixed feelings.

I write to you from a place of mixed feelings, too. But I want to complicate things. Or maybe I just want to have a conversation about writing and life that exists outside the marketplace, outside whatever role the world has assigned to you. People will tell you that such a conversation is a privilege, and maybe it is, maybe you shouldn’t make any life decisions based on it. Then again, maybe you should. You’re allowed to imagine a life for yourself that has nothing to do with your finances, nothing to do with success or failure, nothing to do with what’s sensible or expected or practical or needed. It doesn’t mean you’re delusional. It’s doesn’t mean you’re spoiled or narcissistic. Writing and reading and speaking freely are the basis of any democratic society. We need more people, from a greater variety of backgrounds, to exercise that right. My one piece of advice is to ignore anyone who makes you forget that.

Image Credit: Pexels/Pixabay.