1.

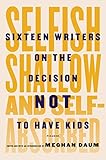

For at least five generations now, women’s lives have been examined in books and newspaper features as a great social riddle. We are encouraged to lean in yet be skeptical of having it all, to call bias as we see it yet pipe down and smile more in meetings to get ahead. Just now, as the season thaws, the cultural conversation on whether to embrace a particular well-worn path — to marry and have children, if one can — is being amped up by a whirl of essays, memoirs, and historical narrative. This week, Random House will publish Spinster: Making a Life of One’s Own by Kate Bolick. In early April, the anthology Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers on the Decision Not to Have Kids, edited by Meghan Daum and featuring essays by men as well as women, came out. These books are the latest volleys in a public debate that has been going on for at least a century. Bolick acknowledges this in Spinster as she reinterprets the lives of five women from the last century — columnist Neith Boyce, essayist Maeve Brennan, visionary writer Charlote Perkins Gilman, poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, and novelist Edith Wharton — all figures who were boldly true to themselves and their ambitions. But beyond those names, hovering in the background, haunting us today from Progressive-Era New York, investigative journalist Ida Tarbell and her now-obscure series The Business of Being a Woman was an essential voice in the beginning of this debate in American media. Her complicated vision, which shifted with the decades and reflected the national upheavals she observed from close quarters, should not be forgotten today.

For at least five generations now, women’s lives have been examined in books and newspaper features as a great social riddle. We are encouraged to lean in yet be skeptical of having it all, to call bias as we see it yet pipe down and smile more in meetings to get ahead. Just now, as the season thaws, the cultural conversation on whether to embrace a particular well-worn path — to marry and have children, if one can — is being amped up by a whirl of essays, memoirs, and historical narrative. This week, Random House will publish Spinster: Making a Life of One’s Own by Kate Bolick. In early April, the anthology Selfish, Shallow, and Self-Absorbed: Sixteen Writers on the Decision Not to Have Kids, edited by Meghan Daum and featuring essays by men as well as women, came out. These books are the latest volleys in a public debate that has been going on for at least a century. Bolick acknowledges this in Spinster as she reinterprets the lives of five women from the last century — columnist Neith Boyce, essayist Maeve Brennan, visionary writer Charlote Perkins Gilman, poet Edna St. Vincent Millay, and novelist Edith Wharton — all figures who were boldly true to themselves and their ambitions. But beyond those names, hovering in the background, haunting us today from Progressive-Era New York, investigative journalist Ida Tarbell and her now-obscure series The Business of Being a Woman was an essential voice in the beginning of this debate in American media. Her complicated vision, which shifted with the decades and reflected the national upheavals she observed from close quarters, should not be forgotten today.

How can one opt out of a social design that so many of us feel pressured to fulfill, without being possessed by regret (or, at the very least, a whole lot of ambivalence)? Is there a working morality that decides which choice is better for everyone? If not, why do so many people feel and act as though there is? I first read Daum on this subject in The New Yorker earlier this year, in her masterful essay “Difference Maker.” That piece’s honesty about the “Central Sadness” of a marriage was like a punch in the chest — and set a daunting example for how honest the rest of us can aspire to be in the narratives we build out of our own lives. Daum’s anthology was reviewed in The New York Times by Bolick, whose book has already been excerpted and discussed in Vogue and Slate. In hearing these contemporary voices weigh in with both confession and argument, it seemed to me there would be value in looking back at earlier manifestoes. I wondered how much, or how little, had changed in the portrayal of that high-consequence negotiation of biology, circumstance, and choice.

2.

Since the early 1900s, the contradictions of living a woman’s life have lurked in the media spotlight as a reliable spark for debate: before Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique and the “problem that has no name,” there was the Uneasy Woman, and the writers who sought to diagnose and save her from uneasiness. Ida Minerva Tarbell was a pioneering journalist — a “muckraker” whose beady eye relentlessly parsed the sins of great tycoons through the early 1900s. But she also had a lesser-known passion: later in her career, she tried to have the last word on her peers’ dissatisfactions with sex, marriage, and gender equality. Born in a Pennsylvania log cabin in 1857, Tarbell rose to stardom at the turn of the 20th century at McClure’s Magazine, where she wrote one of one of the landmark pieces of American reportage, “The History of Standard Oil Company.” A decade later, she began writing essay after essay about “the Uneasy Woman,” and the result was a series in the Ladies’ Home Journal and two now-forgotten books compiled from her dozens of magazine pieces: The Business of Being a Woman (1912) and The Ways of Woman (1915). When I came across Tarbell’s books, it was clear that they were revealing documents. Written in a fluid, authoritative style, as though she is making her arguments to a literary salon of the 1920s, they entertained even as they exasperated and surprised me. How should a female person be? The question occupied hundreds of printed pages a century ago and still does today. Tarbell tried her damnedest to answer it.

Since the early 1900s, the contradictions of living a woman’s life have lurked in the media spotlight as a reliable spark for debate: before Betty Friedan’s Feminine Mystique and the “problem that has no name,” there was the Uneasy Woman, and the writers who sought to diagnose and save her from uneasiness. Ida Minerva Tarbell was a pioneering journalist — a “muckraker” whose beady eye relentlessly parsed the sins of great tycoons through the early 1900s. But she also had a lesser-known passion: later in her career, she tried to have the last word on her peers’ dissatisfactions with sex, marriage, and gender equality. Born in a Pennsylvania log cabin in 1857, Tarbell rose to stardom at the turn of the 20th century at McClure’s Magazine, where she wrote one of one of the landmark pieces of American reportage, “The History of Standard Oil Company.” A decade later, she began writing essay after essay about “the Uneasy Woman,” and the result was a series in the Ladies’ Home Journal and two now-forgotten books compiled from her dozens of magazine pieces: The Business of Being a Woman (1912) and The Ways of Woman (1915). When I came across Tarbell’s books, it was clear that they were revealing documents. Written in a fluid, authoritative style, as though she is making her arguments to a literary salon of the 1920s, they entertained even as they exasperated and surprised me. How should a female person be? The question occupied hundreds of printed pages a century ago and still does today. Tarbell tried her damnedest to answer it.

Steve Weinberg’s 2008 book Taking on the Trust: How Ida Tarbell Brought Down John D. Rockefeller and Standard Oil describes Tarbell living alone in New York City in a handsome red-brick building at 40 West Ninth St. Her independence was concentrated by a dose of fear that she would end up like her mother, Esther, a women’s rights advocate and teacher who had given up her job after getting married. Esther’s life had been governed by the vagaries of her husband’s career and the needs of their babies. Ida, their first child, knew from an early age that she wanted something else: “I must be free; and to be free I must be a spinster. When I was fourteen I was praying God on my knees to keep me from marriage,” she wrote in her memoir, All in a Day’s Work. So she set her eyes on college, and beyond that, on making her own way. As adulthood wore on, things got more complicated.

Steve Weinberg’s 2008 book Taking on the Trust: How Ida Tarbell Brought Down John D. Rockefeller and Standard Oil describes Tarbell living alone in New York City in a handsome red-brick building at 40 West Ninth St. Her independence was concentrated by a dose of fear that she would end up like her mother, Esther, a women’s rights advocate and teacher who had given up her job after getting married. Esther’s life had been governed by the vagaries of her husband’s career and the needs of their babies. Ida, their first child, knew from an early age that she wanted something else: “I must be free; and to be free I must be a spinster. When I was fourteen I was praying God on my knees to keep me from marriage,” she wrote in her memoir, All in a Day’s Work. So she set her eyes on college, and beyond that, on making her own way. As adulthood wore on, things got more complicated.

Higher education and careers were opening up to women for the first time, and women’s suffrage seemed to be just over the horizon. Recent technologies, the typewriter and then the telephone, meant a steady rise in secretarial jobs. The media called the suddenly visible population of educated, outgoing young ladies New Women: they rode bicycles, played tennis, wore skirts that showed some ankle, and appeared in Charles Dana Gibson’s pen-and-ink drawings. But while the Gibson Girls on the page were always nattily dressed and never political, the New Woman was in practice wary that having a family almost always meant giving up any public influence she had already earned. As one of Tarbell’s fellow newspaperwomen, Rheta Childe Dorr, put it, women increasingly sought “to belong to the human race, not the ladies’ aid society to the human race.”

In the hot August of 1891, Ida Tarbell gave up her cozy job as managing editor of the journal The Chautauquan and moved to Paris. She wanted to write full-time and taste life outside small-town Pennsylvania. She threw herself into cafe life and became fascinated with the militant feminists of the French Revolution, who had preached a different way of life over two centuries earlier. “Celibacy is the aristocracy of the future” was one of their slogans, and in her library chair at the Sorbonne, Tarbell carefully copied it into her notebook.

Celibacy, or at least independence, made Tarbell’s life the freewheeling, over-achieving affair that it was. But once she moved from Paris to New York and made her name at McClure’s, she was alarmed to be seen as a role model. Reading her Ladies’ Home Journal columns today, it’s clear that for her suffrage and spinsterhood had trade-offs that didn’t have much to do with success or happiness. She preached instead that the “feminine unrest” was the result of mistaking sameness for equality. “[Women] cannot be made equal by exterior devices like trousers, ballots, the study of Greek,” she insisted; “The central fact of the woman’s life — Nature’s reason for her — is the child.” The subject was inescapable and exhausting. “The most conspicuous occupation of the American woman of to-day, dressing herself aside,” Ida Tarbell chided, “is self-discussion.”

Alternately starry-eyed and detached towards the community of women she was addressing, she wrote herself into the story as a fluke, one of the few “bachelor souls” whose homes were full of beautiful things but empty of the “sweet human litter” that made it other than a “meatless shell.” Tarbell’s meatless shell was a postcard-perfect farm in Connecticut where she entertained Mark Twain and kept a pig named Juicy, but she did her best to brush off those who wanted to follow in her footsteps. “A few women in every country have always and probably always will find work and usefulness and happiness in exceptional tasks,” she wrote. “[They] are not the ones who build the nation.”

There are few real answers here for the Uneasy Woman, apart from to appreciate the awesome responsibility of raising well-adjusted babies. The problem with society, Tarbell was sure, was the way it handled the way those babies were made. The Uneasy Woman would never have gotten that way if it hadn’t been for two all-too-pervasive ideas: first, that sex should be completely ignored until marriage; and second, that marriage meant submission. Sex was not frankly discussed with young people, though children rarely came of age without figuring out the facts of life. Tarbell was disdainful of the deep-seated cultural secrecy and hysteria surrounding the subject and the harm that it did to relationships and families. A young woman embarking on marriage at the turn of the century, Tarbell wrote, “is like a voyager who starts out on a great sea with no other chart than a sailor’s yarns, no other compass than curiosity.” Even if that curiosity brought satisfaction instead of disappointment (or worse), it often came with hefty consequences. Through the 19th century, withdrawal and abortion were the most common methods of family planning, and many married couples had children earlier and in greater number than they would have liked.

Divorce and separation rates rose faster in the Progressive Era than ever before, and social scientists turned their attention to this sudden trend. Many of them argued that its stigma should be removed, and that men and women should equally have the authority to leave a failed marriage. Tarbell, for her part, was jaded by the number of women she knew who had sacrificed their values and interests for the sake of a superficially tranquil marriage. “Peace which comes from submission and restraint is a poor thing,” she wrote. It was an alluring trap, one disguised as security for both people in the marriage, but it would inevitably make a woman “less interesting, less important, both to herself and to him.”

3.

What’s eye-catching about Tarbell’s writing here is not that she was a bad feminist with some progressive ideas. In her published writing she was, as Kathleen Brady wrote in Ida Tarbell: Portrait of a Muckraker, “a weathervane, not an engine of change.” Privately, though, she chafed against the boundaries and tried to live as though they did not apply to her. It’s the way her own uncertainty and frustration — her own Unease — bubble up in her writing when her guard is down. The fact that she was a woman sometimes excluded her from the more clubby, sociable aspects of New York journalism. “The whole office goes on Thursday to the publishers’ dinner,” she wrote in a letter, “– that is, everybody but myself. It is the first time since I came into the office that the fact of petticoats has stood in my way, and I am half inclined to resent it.” Her editor at McClure’s had encouraged her to tell the stories she wanted to tell, but later in her career, she hit a glass ceiling that took her by surprise. At the American magazine, which she co-founded, a male colleague began to reject her editorials, saying, “You sputter like a woman” — and Tarbell, retelling the scenes years later, couldn’t shake the worry that he was right.

What’s eye-catching about Tarbell’s writing here is not that she was a bad feminist with some progressive ideas. In her published writing she was, as Kathleen Brady wrote in Ida Tarbell: Portrait of a Muckraker, “a weathervane, not an engine of change.” Privately, though, she chafed against the boundaries and tried to live as though they did not apply to her. It’s the way her own uncertainty and frustration — her own Unease — bubble up in her writing when her guard is down. The fact that she was a woman sometimes excluded her from the more clubby, sociable aspects of New York journalism. “The whole office goes on Thursday to the publishers’ dinner,” she wrote in a letter, “– that is, everybody but myself. It is the first time since I came into the office that the fact of petticoats has stood in my way, and I am half inclined to resent it.” Her editor at McClure’s had encouraged her to tell the stories she wanted to tell, but later in her career, she hit a glass ceiling that took her by surprise. At the American magazine, which she co-founded, a male colleague began to reject her editorials, saying, “You sputter like a woman” — and Tarbell, retelling the scenes years later, couldn’t shake the worry that he was right.

It took time, war, and a chance meeting to change her mind. During the First World War, Woodrow Wilson appointed her to the 11-member Council of National Defense Woman’s Committee. As she got to know another woman on the committee, Anna H. Shaw, Tarbell’s convictions began to change. Shaw, the president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, didn’t try to befriend Tarbell right away because of her anti-suffrage stance, but Tarbell admired Shaw more and more as they worked together. “She was so able, so zealous, so utterly given to her cause,” Tarbell marveled. “…most warm-hearted…as well as delightfully salty in her bristling against men.” They became friends, and gradually, Tarbell’s tone changed. She became more of a devil’s advocate for feminist causes, questioning them sympathetically instead of brushing them aside.

For the October 1924 edition of Good Housekeeping, Tarbell wrote a long investigation titled, “Is Woman’s Suffrage a Failure?” It had been four years since women had won the vote, and Tarbell took a road trip across America to research the story. She enthusiastically reported on the women she met who held public office, and concluded that a woman could lead a nation just as well as a man: “Consider Catherine of Russia…Elizabeth of England, Catherine de Medici. And it was of Marie Antoinette that Mirabeau said she was the only man the king had about him.” It took substantial hindsight, but Tarbell had decided that the flukes, the “bachelor souls” who pursued power and success in public life, were as much the Everywoman as those who were wives and mothers first. Her narrative, printed and sold across America, had decisively changed.

Ida Tarbell lived through monumental events in American history: the Civil War, Great Depression, two World Wars, and the invention of Thomas Edison’s light bulb, Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone, the car, and airplane, to name a few. She saw slaves freed and women get the vote, and she turned her critical, curious gaze on it all. But when it came to the Business of Being a Woman, she had to fight with herself as much as with others to come to a working conclusion. It took years of writing and unrest to realize what it was that she really wanted to see in the world.