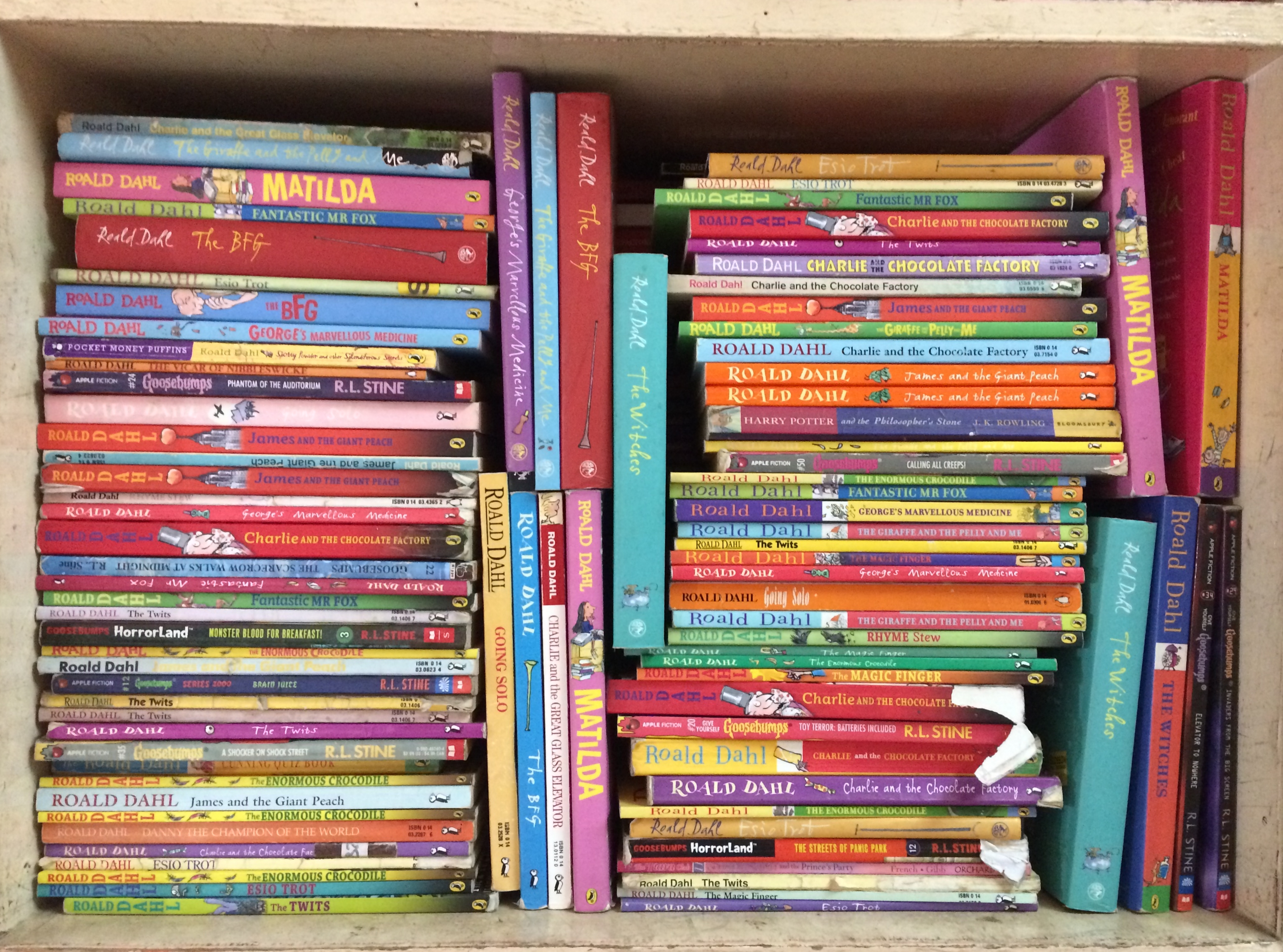

My son turned six in March, and among the many presents he received on his birthday—Hot Wheels tracks, Lego sets, a bag of eerily gelatinous sand—was Roald Dahl’s Danny the Champion of the World. This gift came from me, intended as the latest in a string of Dahl books that my wife and I have read to him in recent months: Matilda, The Magic Finger, Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. Though I’d never heard of Danny before buying it, its description seemed right up my son’s alley: a young boy and his dad exact vengeance on a wealthy twit by stealing all his pheasants. Who doesn’t like pheasant theft?

We’d steered him towards such storybooks about a year ago, when we introduced E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web to his steady diet of picture books. I wasn’t sure how he would take to Charlotte, with its rural setting and homicidal barnyard talk (“Almost all young pigs get murdered by the farmer…there’s a regular conspiracy around here to kill you at Christmastime”). But, like Templeton the rat slurping at a rotten egg, my son happily ate it up. He also enjoyed White’s Stuart Little, though it nearly bored me into a coma. But what I found dull and episodic, he thought of as cool. After all, Stuart is a mouse who drives a wind-up car.

We’d steered him towards such storybooks about a year ago, when we introduced E.B. White’s Charlotte’s Web to his steady diet of picture books. I wasn’t sure how he would take to Charlotte, with its rural setting and homicidal barnyard talk (“Almost all young pigs get murdered by the farmer…there’s a regular conspiracy around here to kill you at Christmastime”). But, like Templeton the rat slurping at a rotten egg, my son happily ate it up. He also enjoyed White’s Stuart Little, though it nearly bored me into a coma. But what I found dull and episodic, he thought of as cool. After all, Stuart is a mouse who drives a wind-up car.

After years of reading picture books to my son, this transition has been, like so many as a parent, an instance to make me stop and see that the kid is growing—like a lost front tooth or the need to buy bigger shoes. To be sure, he still likes children’s books; Mo Willems and Dr. Seuss remain very easy sells. But he approaches these longer, sparsely-illustrated stories with a new and eager seriousness, as if each is its own small project. When I ask him if he’s in the mood to hear Charlotte’s Web or Danny, it’s like asking if he wants to head outside to tinker with the car. “Sure,” he’ll say after a pause, his head cocked in consideration. “Yeah, let’s read it.”

After years of reading picture books to my son, this transition has been, like so many as a parent, an instance to make me stop and see that the kid is growing—like a lost front tooth or the need to buy bigger shoes. To be sure, he still likes children’s books; Mo Willems and Dr. Seuss remain very easy sells. But he approaches these longer, sparsely-illustrated stories with a new and eager seriousness, as if each is its own small project. When I ask him if he’s in the mood to hear Charlotte’s Web or Danny, it’s like asking if he wants to head outside to tinker with the car. “Sure,” he’ll say after a pause, his head cocked in consideration. “Yeah, let’s read it.”

Unlike the way he interacts with an Elephant and Piggie book or If I Ran the Zoo—a kind of wouldja-look-at-that sort of romp—his engagement with White and Dahl has been vastly different. There’s so much more to follow in these books, and so much he can’t understand. “I eased my foot off the accelerator,” says Danny as he tries to drive a car. “I pressed down the clutch and held it there. I found the gear lever and pulled it straight back, from first into second. I released the clutch and pressed on the accelerator.” What six-year-old (or, for that matter, 36-year-old) can keep such action straight? And why would my son sit still for it? If that scene had come in a Willems book, he would have squirmed like a worm on a hook. Any sustained lull in a picture book usually spells doom; a mild desperation comes over me when things aren’t “fun” enough, and I can feel my son growing restless.

Unlike the way he interacts with an Elephant and Piggie book or If I Ran the Zoo—a kind of wouldja-look-at-that sort of romp—his engagement with White and Dahl has been vastly different. There’s so much more to follow in these books, and so much he can’t understand. “I eased my foot off the accelerator,” says Danny as he tries to drive a car. “I pressed down the clutch and held it there. I found the gear lever and pulled it straight back, from first into second. I released the clutch and pressed on the accelerator.” What six-year-old (or, for that matter, 36-year-old) can keep such action straight? And why would my son sit still for it? If that scene had come in a Willems book, he would have squirmed like a worm on a hook. Any sustained lull in a picture book usually spells doom; a mild desperation comes over me when things aren’t “fun” enough, and I can feel my son growing restless.

But with White and Dahl and others, a lack of entertainment has not been a problem. Their books send my son to a different mental area—a deeper, spongier chamber. With no foxes in socks or bifocaled elephants, he’s forced to focus inward, where he creates the pictures himself. This is, of course, no revelation; it’s what reading is. But to see a child venture into this place for the first time has been both heartening and strange. What is he seeing in there? An animated version of Quentin Blake’s artwork? A chaotic Peter Max jumble? Something more cinematic? There is no way to know.

And it ultimately may not matter. I’m beginning to think that when my wife and I read these books to him, the story itself is somewhat beside the point. I suspect that the real draw, for him, is not just the chance to find out what happens in the next chapter, but to nestle in beside us on his football-shaped beanbag chair. Because Dahl doesn’t just make our son think differently; he draws him to us. There’s something about having to direct the action himself that makes him nudge in closer as we read. It’s as if, finally forced to explore a story without the guidance of pictures, he wants us to be near—like when he’s walking through the house after it’s gotten too dark to see.

My fondest memories of my father have to do with the same moment in my own childhood, when he read me Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. My dad had been in a classic-book-of-the month club, and his Mark Twain volumes were sturdy, slipcovered editions with plates of N.C. Wyeth art. I doubt I understood much in these books beyond their characters’ bare actions—the fence-painting, the river-rafting, the girl-irritating—and I remember almost nothing from them now. But the feeling of being on my dad’s lap, his voice deep and sonorous above me, has stuck with me through the years. His reading enabled a warmth and a closeness that otherwise wasn’t much there. He could’ve been reading the dictionary, and I would have sat there, rapt.

My fondest memories of my father have to do with the same moment in my own childhood, when he read me Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. My dad had been in a classic-book-of-the month club, and his Mark Twain volumes were sturdy, slipcovered editions with plates of N.C. Wyeth art. I doubt I understood much in these books beyond their characters’ bare actions—the fence-painting, the river-rafting, the girl-irritating—and I remember almost nothing from them now. But the feeling of being on my dad’s lap, his voice deep and sonorous above me, has stuck with me through the years. His reading enabled a warmth and a closeness that otherwise wasn’t much there. He could’ve been reading the dictionary, and I would have sat there, rapt.

Because of this dynamic—the storybook’s drawing of the child to the reader—I feel closer to my son when we’re reading Roald Dahl. For all the talk of the importance of reading to your child—often eat-your-peas harangues that have more to do with a fear of future failure than enjoyment of the actual act—the emotional and physical closeness that reading facilitates doesn’t get much play. But given my own Mark Twain memories and what happens on the beanbag chair, I’ve come to consider such closeness to be vital and unique. I can think of no other time that my son will sit, his head propped on my shoulder, for a half an hour or more. That I can sense the drama popping in his mind as I read is an obvious added bonus. Reading storybooks has put us at the neat intersection of stillness and excitement.

My wife is currently reading him Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator, which, as I understand it, takes Charlie into 2001 territory. Meanwhile, we’re closing in on the end of Danny the Champion of the World; we should finish in a couple of days. It’s a quiet, almost sad little story about fighting your own insignificance. But, of course, my son just likes to hear about pheasant poaching and making a rich guy mad. As I’d hoped when he unwrapped it on his birthday, he loves Danny, and begs pathetically for more when I stop reading for the night. Sometimes I give in and read another page or two. All I ask in return is that he’ll remember it fondly 30 years from now.

My wife is currently reading him Charlie and the Great Glass Elevator, which, as I understand it, takes Charlie into 2001 territory. Meanwhile, we’re closing in on the end of Danny the Champion of the World; we should finish in a couple of days. It’s a quiet, almost sad little story about fighting your own insignificance. But, of course, my son just likes to hear about pheasant poaching and making a rich guy mad. As I’d hoped when he unwrapped it on his birthday, he loves Danny, and begs pathetically for more when I stop reading for the night. Sometimes I give in and read another page or two. All I ask in return is that he’ll remember it fondly 30 years from now.

Image Credit: Flickr/solarisgirl.