1.

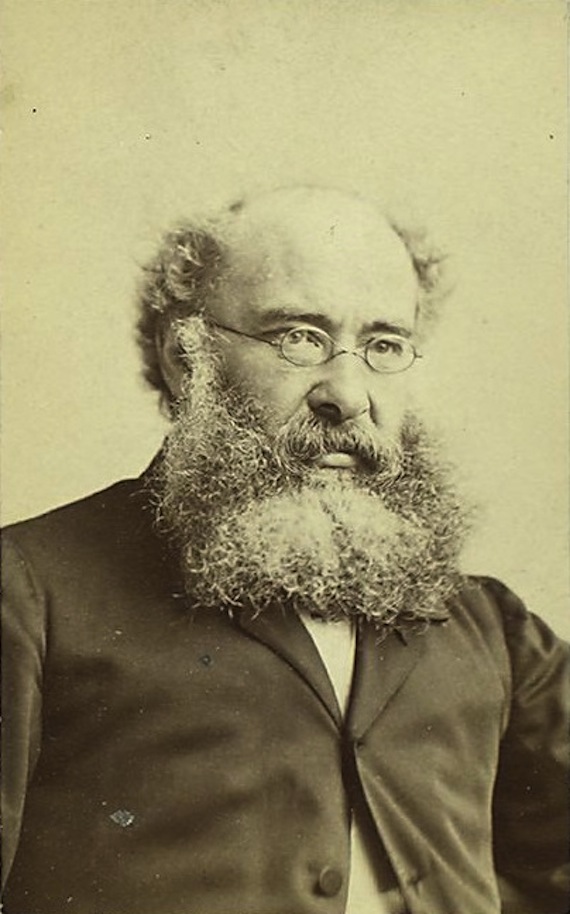

English novelist Anthony Trollope (1815-1882) was born in London 200 years ago this April, and his bicentennial will be marked with a flurry of seminars, readings, and exhibits. His longtime employer, the British postal service, will release a set of commemorative stamps to honor the man who, in addition to being a national literary figure, is credited with introducing the pillar box to Britain. While both fitting and timely, such tributes are only the latest in a decades-long series of efforts to memorialize Trollope and to ensure that his novels receive the popular and scholarly attention they deserve. He is still typically excluded from the first rank of British novelists, but Trollope’s realistic stories about ordinary people are among the greatest critical appreciations of life in a democratic age.

The last 30 years have been “fat” ones for Trollope. Trollope Societies have been established in the United Kingdom and in the United States, with the original U.K. Society organizing the first complete edition of his works. In 1993, a memorial stone honoring Trollope was laid in Westminster Abbey’s Poets’ Corner, and since 2011, the University of Kansas has awarded literary prizes to encourage the “reading, study, and teaching” of Trollope’s novels.

Most everything of significance that is known about Trollope’s life is contained in his posthumously published An Autobiography (1883). There, he recounts his miserable and undistinguished days as an English schoolboy and his strategy for managing his dual careers as civil servant and author, which overlapped considerably. To write while continuing to fulfill his duties at the post office, Trollope adopted an exacting work regimen that consisted of rising every morning at 5:30 and reading the previous day’s work before writing, at a rate of 250 words per quarter hour, for two-and-a-half hours.

Most everything of significance that is known about Trollope’s life is contained in his posthumously published An Autobiography (1883). There, he recounts his miserable and undistinguished days as an English schoolboy and his strategy for managing his dual careers as civil servant and author, which overlapped considerably. To write while continuing to fulfill his duties at the post office, Trollope adopted an exacting work regimen that consisted of rising every morning at 5:30 and reading the previous day’s work before writing, at a rate of 250 words per quarter hour, for two-and-a-half hours.

Many words were written as a consequence of this “habit of industry” and refusal to “nibbl[e] his pen” or wait for his muse. Whether his muse withheld her favors as a result of such scorn is a matter of debate, but in any event many objected to the vulgarity of the notion that novels worth reading could be produced by keeping to a schedule. Writing a few years after Trollope’s death, George Bernard Shaw observed that “society has not yet forgiven that excellent novelist for having worked so many hours a day, like a carpenter or tailor, instead of periodically going mad with inspiration and hewing Barchester Towers at one frenzied stroke out of chaos, that being the only genuinely artistic method.” Of equal concern to proponents of the ideal of the true artiste was Trollope’s confession in the Autobiography that he wrote in part for the same reason the “baker…sets up his oven:” to make money.

Many words were written as a consequence of this “habit of industry” and refusal to “nibbl[e] his pen” or wait for his muse. Whether his muse withheld her favors as a result of such scorn is a matter of debate, but in any event many objected to the vulgarity of the notion that novels worth reading could be produced by keeping to a schedule. Writing a few years after Trollope’s death, George Bernard Shaw observed that “society has not yet forgiven that excellent novelist for having worked so many hours a day, like a carpenter or tailor, instead of periodically going mad with inspiration and hewing Barchester Towers at one frenzied stroke out of chaos, that being the only genuinely artistic method.” Of equal concern to proponents of the ideal of the true artiste was Trollope’s confession in the Autobiography that he wrote in part for the same reason the “baker…sets up his oven:” to make money.

While Trollope’s extensive bibliography also includes short stories, travel writing, general interest biography, and countless periodical pieces, his literary reputation has always hinged on assessments of his 47 novels. The author well understood that this would be so and indeed hoped he had fashioned a few characters that might provide the foundation of some “permanence of success.” In Trollope’s estimation, these characters were likely to be the Reverend Mr. Crawley, who appears in two of the six Barchester or “clerical” novels, and Plantagenet Palliser and his wife, Lady Glencora, personnages principals of the Palliser or “political” novels.

2.

In a letter to George Eliot, Trollope acknowledged that his novels focused on the “little people” as opposed to the “great names” about whom Eliot had sometimes written. For heroes and heroines Trollope offers us such figures as Miss Mackenzie, a dull and unattractive spinster in her mid-30s; the aforementioned Mr. Palliser, a patriotic yet weak statesman who will not make an indelible mark on the history of his country; and Eleanor Arabin, a naïve, sweetly dutiful daughter and wife. While the little people were not “equal as subjects to the great names,” being little did not amount to being insignificant or disqualify one from being a subject worthy of a serious author. Thoroughly convinced that every woman — even Miss Mackenzie — had a story of interest to herself, Trollope also believed that most people’s stories, well told, could be made interesting to others.

According to Trollope, the novelist ought to be true to human nature, by which he meant ordinary human nature. Novels should present human beings in their diverse typicality, not extraordinary men and women in extraordinary situations. In the Autobiography, he said that he had always sought “to make men and women walk upon [‘some lump of the earth’] just as they do walk here among us.” He wanted his readers to recognize themselves in his characters and “not feel themselves to be carried away among gods or demons.”

Trollope’s novels are indeed full of ordinary people preoccupied with the most mundane things. They care about the price of corn, angle to secure a coveted dinner party invitation, and dread interviews with ladies to whom they have made promises that cannot be kept. In the Barchester novels, there is much ado about the fate of the wardenship of a small hospital, and two rival doctors battle for preeminence in the county. For the men and women involved, these are thought to be matters of life and death.

As they grapple with their little dilemmas, ordinary men and women bumble about with imperfect self-knowledge and a greater ability to feel than to articulate their feelings. The universe they inhabit is also morally complex, and in navigating it they are perfect neither in their virtue nor their vice. Trollope gives us the cad who is not quite entirely caddish, the woman who works hard to maintain a prudent marriage without forgetting the imprudent one she had herself wanted. Nothing could be less like Dickens’s stark portraits of saints and fiends — portraits Trollope described as charming “puppets” — moving through a black-and-white world in which the roads to perdition and redemption, though possible to miss, are nonetheless clearly marked.

Even Trollope’s high-ranking and ambitious characters are not without the quality of littleness. In the Palliser novels, Plantagenet Palliser eventually becomes Duke of Omnium and serves for three years as Prime Minister of England. Mr. Palliser is sensitive, socially awkward, and occasionally insecure, and in him Trollope intentionally gives us a statesman who is not “a Pitt or a Peel or a Palmerston.” Once at the head of Her Majesty’s government, the Duke is stirred by ambition and suffers as a consequence of the knowledge that destiny had not made him a great leader of men. Among the foremost of Trollope’s heroes, Mr. Palliser is simply not that impressive.

As compensation for our inability to admire Mr. Palliser as we would a Cyrus, an Alexander, or a Lincoln, we are allowed to know and understand him. After introducing his statesman in one of the Barchester novels, Trollope uses his characteristic method to delineate the man’s character over the course of the Palliser novels. This method of developing and revealing character consists in conducting the subject through a series of incidents that are quite ordinary in themselves. Trollope hovers a magnifying glass over these tête-à-têtes, country strolls, and family breakfasts. On many occasions we observe Mr. Palliser hesitate, sigh, look askance, feel he has said too much or too little, and doubt his own good intentions. While the reader quickly learns not expect greatness of Mr. Palliser, he desires that Mr. Palliser be true to his noble, generous, liberal nature. Trollope declared that he “love[d]” Plantagenet Palliser, and if to know is to love, the reader who has observed Mr. Palliser’s development over 20 years and many hundreds of pages might well be similarly devoted.

It is not without a hint of nostalgia for the epic, tragic, and heroic that Trollope commits himself to working within a limited dramatic horizon. For example, all the while taking seriously his characters’ agonies and ecstasies, he is not above gently mocking the gap between their self-seriousness and the objective smallness of the stakes, as when he likens the “collision” between the two Barchester doctors to the confrontation between Hector and Achilles. Trollope realized, however, that the age of demigods and heroes had given way to an age of equality in which the little person held center stage. His portrayals of the complexities and ambiguities of ordinary life both reflect this shift and attempt to make the most of it by cultivating the moral imaginations of his readers — men and women who must, in one way or another, come to terms with the modern world.

3.

Trollope hoped that he might still be read in the next century. He has done better than this, but his reputation as an author has long been a mixed one.

Trollope’s ability to create realistic impressions of life and character has earned him many admirers. Nathaniel Hawthorne claimed that Trollope’s novels were “just as real as if some giant had hewn a great lump out of the earth and put it under a glass case, with all its inhabitants going about their daily business, not suspecting that they were made a show of.” According to Virginia Woolf, “The Barchester Novels tell the truth…We believe in Barchester as we believe in the reality of our own weekly bills.” For Henry James, Trollope’s particular “genius” was his “happy, instinctive perception of human varieties.” He had a keen “knowledge of the stuff we are made of” and was interested in “all human doings.”

Despite the success of what he called his “real portraits,” Trollope’s most astute critics have also doubted that he possessed all of the requisites of a great novelist. In his diary, Leo Tolstoy wrote, “I despair for myself” and that Trollope “overwhelms me with his skill,” but the following day’s entry protests that there is “too much that is conventional” in Trollope. James argued that despite Trollope’s “genius,” his stature was diminished by, among other things, long-windedness, a “mechanical” writing process, formulaic prose, an imagination that was not original but merely reflective, a “wanto[n]” tendency to disturb — mid-story — the illusion that his characters and story were real, and a failure to think in any systematic way about the novel form or what it meant to be an “artist.” In short, although he was a master of realism and human psychology, Trollope lacked the refined style and expansive creative powers of an unqualified master.

In some cases, Trollope’s novels could have been shorter and more carefully edited without sacrificing his overall design. Many of his books were first serialized, and the need to fill a certain number of pages at stated intervals no doubt led him to multiply scenes and sub-plots. Without a few of these, Trollope would still be Trollope.

Generally speaking, though, substantial length, a leisurely pace, and prosy prose were artistically necessary for Trollope. If his end was to offer his readers “human beings like to themselves,” the acquaintance must be made gradually through repeated interactions, as in real life, where one does not come to know another person all at once. Ordinary life is also a mixture of novelty and sameness — the new face or development that appears amidst a sea of routines and similar episodes that Trollope typically manages to set off from one another with the subtlest of verbal wrist flicks.

When it encounters the great variety within the universe of the ordinary, commonplace, and relatively predictable, the soul rarely takes flight. It does, however, expand as it proceeds to recognize itself in others and to appreciate their diverse struggles and preoccupations. Trollope abided no romance, opting instead to observe with generosity the world around him — a world full of little people doing little things. Each and every one of these people has a story to tell, and Trollope shows that listening can be entertaining as well as good for the soul.

Image Credit: Wikipedia.