Kazuo Ishiguro writes novels set in a diversity of realms — the Japanese underworld, the Central Europe of Franz Kafka, the English countryside of Oswald Mosley. But no matter their territory, his stories share a few key features: they all deal with the complexities arising from a seemingly simple proposition, and they are all sad as shit. A butler takes a trip to solve his staffing issues; he faces the be-waistcoated shambles of his life. A woman reflects banally on her schooldays, while organs are harvested all around. A man arrives in a city to give a concert — he can’t do it, but why?

In The Buried Giant, an elderly man and woman set out on a visit to their son. But this journey is a production. They live in a way-back-England where Christians and pagans and ogres mingle. Their village, and all neighboring villages, have been enveloped in a mist that makes everyone forget what they have done and what they are about to do (Ishiguro is the king of maddening obstacles). This mist is, according to various theories, the result of God himself forgetting his people, or the enchanted breath of an elderly dragon named Querig. Mist notwithstanding, the couple, Axl and Beatrice, are spurred by some deep and nameless instinct to visit a son they only vaguely remember, convincing themselves en route that he is eagerly anticipating their arrival. Along the way they also get mixed up with mythical characters, Arthurian and older, and contemplate the nature of their love for one another.

At some moments, I felt I had found an apocryphal eighth Chronicle of Narnia, written by a particularly cheerless, possibly aphasic disciple of C.S. Lewis. While Ishiguro’s “turn to fantasy” has been compared to J.R.R. Tolkien and, heaven forfend, George R.R. Martin, the Christian allegory and honor-bound Britishness of Lewis is where I think the novel is more at home. If you remember Eustace Scrubb and Jill Poole and Puddleglum making their way across the terrible moor and through the ruined giant city, you’re there with Beatrice and Axl as they struggle across the Great Plain where the giant lies buried, always on the lookout for enchantments. Even the narrative perspective nods, intentionally or no, to Lewis, in its occasional breaks to address the reader, breaks that are just enough to remind you that you aren’t alone in the room. The third-person omniscient narrator Ishiguro employs for much of the novel places the reader in time in much the same way that Lewis’s did: “Once inside it, you would not have thought this longhouse so different from the sort of rustic canteen many of you will have experienced in one institution or another.” Compare to Lewis’s friendly signposts: “You have never seen such clothes, but I can remember them,” or “They came out on one of those rough roads (we should hardly call them roads at all in England)”.

If, in a Narnian finale, everyone gets to be together again, in an Ishiguran one, everyone is destined to be apart. But in any case, Ishiguro’s “turn to fantasy,” if that’s what we want to call it, is not what is odd about this novel, which is of a piece with his established weirdness, his postmodern genre flirtations.

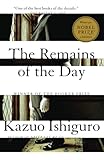

Ishiguro has a reputation for spare, even aggressively unadorned prose. In the very perfect novel The Remains of the Day, Stevens the butler explains the beauty of England, in what might be a uniquely oblique authorial humble brag:

Ishiguro has a reputation for spare, even aggressively unadorned prose. In the very perfect novel The Remains of the Day, Stevens the butler explains the beauty of England, in what might be a uniquely oblique authorial humble brag:

And yet what precisely is this ‘greatness’? Just where, or in what, does it lie?…I would say that it is the very lack of obvious drama or spectacle that sets the beauty of our land apart. What is pertinent is the calmness of that beauty, its sense of restraint. It is as though the land knows of its own beauty, of its own greatness, and feels no need to shout it.

The Buried Giant is so restrained that it sometimes has a soporific effect not unlike the mist that is its central proposition. Moreover, there are some strange and disorienting perspectival shifts. We are with Beatrice and Axl very closely at the beginning, seeing things from Axl’s point of view as they are relayed by a seemingly featureless and disinterested narrator (“As she said this, softly into his chest, many fragments of memory tugged Axl’s mind, so much so that he felt almost faint.”). It is jarring then, half-way through the novel, when this perspective shifts to another character, or gives over to the first-person musings of Gawain (“Was she not that way, the one I sometimes remember when there stretches before me as much land, empty and companionless, as I could ride on a dreary autumn’s day?”). The story becomes difficult to follow when the action picks up, at a monastery full of monks who engage in a perverse and memorable bird-related form of penitence; we occasionally jump forward slightly in time and then recover lost ground using the past perfect tense (“They had met in the chilly corridor outside Father Jonus’s cell.”) Since they are written by Kazuo Ishiguro, these shifts must at heart be measured and purposeful — but they seem haphazard; they are sometimes confusing.

Unless you have utterly professionalized as a reader, the books you read are always going to be about what is going on in your life, to the extent that deluded readers like myself will see the hand of divine providence or some otherwise cosmic coincidence in their reading. I think that had I been in another frame of mind I may have dismissed this novel, placed it on a lower shelf in the Ishiguro cabinet of curiosities. But I happened to finish The Buried Giant the day after I returned to work from maternity leave, with a 10-week-old baby still at home. So, for one, I am in a state of high emotion such that I was inclined to read the novel as a love story about old people and dead children, and weep accordingly. (Without spoilers, I will say that the ending of the novel is very much like a very sad poem by

In The Buried Giant, the mist functions as a prophylactic against bloodshed — the Britons and Saxons had hitherto been embroiled in perpetual and gruesome war — but it does not feel like benevolence. In an interview published in The Times, Ishiguro said that he wanted to write about collective memory without the limitations of a contemporary setting: “I wanted to put it in some setting where people wouldn’t get too literal about it, where they wouldn’t think, oh, he’s written a book about the disintegration of Yugoslavia or the Middle East.” Grotesque human behavior is always lurking around the edges of the novel and in the memories of its characters, as one of the knights graphically explains:

But they know in the end they will face their own slaughter. They know the infants they circle in their arms will before long be bloodied toys kicked about these cobbles. They know because they’ve seen it already, from whence they fled. They’ve seen the enemy burn and cut, take turns to rape young girls even as they lie dying of their wounds. They know this is to come, and so must cherish the earlier days of the siege, when the enemy first pay the price for what they will later do. In other words, Master Axl, it’s vengeance to be relished in advance by those not able to take it in its proper place. That’s why I say, sir, my Saxon cousins would have stood here to cheer and clap, and the more cruel the death, the more merry they would have been.

If an imagined world at the back of a wardrobe gave C.S. Lewis the basis for drawing all of Christianity, Ishiguro found a way to amplify his Arthurian moment to a universal scale. The Buried Giant is about war and memory, but it is also about love and memory, and you don’t need to have lived through an atrocity to get it. While the various knights are concerned with the mist’s implications for tribal enmities, the real constant in the story is Beatrice and Axl’s marriage. Whatever wrongs they may have committed against one another are in the past; what we see now is Axl’s constant use of the endearment “princess,” the way he doesn’t want to leave her side. The problem is that all of their past happiness is obscured by the mist, along with all of the wrongs.

Memory has been on my mind lately. Our weeks home with the baby were an enchanted time, the joys and the terrors achieving religious proportions. Life was a welter of soft skin and wooly socks and blankets and delight, interrupted here and there by the jagged edge of existential dread, the raw surprise of a sore nipple against a flannel shirt, or a torn muscle, or a panic about measles. Every day of my precious 10 weeks I told myself “you have to remember this.” But as I approached the moment when I would have to resume my business casual and normal life, the feelings began to ebb; the memory of the newness and wonder of those first days lost a bit of its technicolor brilliance. I look at pictures on my phone and am surprised by the little face as it was on day two and day five and day 21. I can call back the moment of her birth and picture how the room was arranged, but I can no longer examine it from different angles; I can no longer feel just exactly how I felt. This is terrible, but I suppose it is also a mercy; you can’t go about your ordinary life in that kind of heightened state.

Another thing that is terrible: I had heard all about how hard it is for many new mothers to leave their infants at home in exchange for workplace squabbles and awkward half-hours spent half-clad, crying and seething alone with breast pump in a dingy supply closet. But that part was fine; it wasn’t until I returned home that first day, my steps quickening to a run up our dark street toward my baby, that I felt for the first time the mute and terrible pull that must be at the root, I suppose, of parenthood — the feeling that made Beatrice and Axl up and set off across the bewitched Great Plain to their son. And it wasn’t until I got home to find the baby already asleep that I faced up to the new arrangement of my life and felt the profound devastation of being apart, a feeling that I could only pray would fade, even as part of me felt it shouldn’t fade — because shouldn’t I feel that it’s terrible, if it is in fact terrible? Shouldn’t I live with the badness, and try to correct it? This is exactly the choice with which the characters in The Buried Giant must contend.

Ishiguro often writes about memory, about the deeply revisionist histories of people who are only poking around the edges of the truth of their lives. Already, as I type this, a seasoned working mom with a week under my belt, each homecoming is increasingly less fraught, the deep sense of futility and sadness I felt on that first day away from the baby has faded, just as that raw, panicked love I felt those first few days after birth has faded, just as the pain in my nether-regions has faded. Ishiguro wrote about the erasure of misery and joy from our memory. But in an ordinary life you don’t need a dragon’s breath to wipe all that away. It’s time that does it, and it only takes a moment.