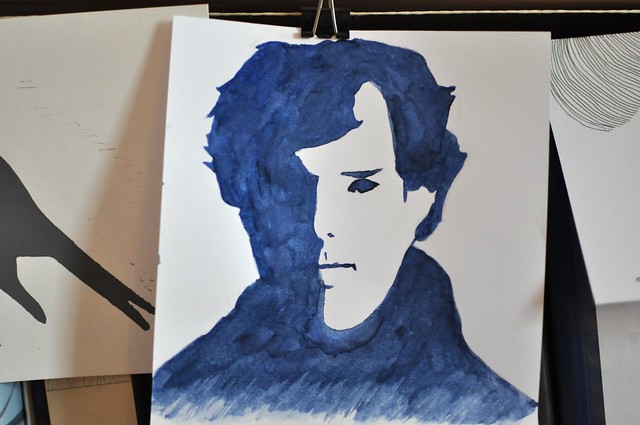

It’s starting to feel like spring the morning that the Dinky, the shuttle that runs between Princeton Junction and Princeton University, deposits us on the edge of campus. There’s still plenty of snow on the ground, but the students milling past us are ambitiously channeling summer, bare arms and legs, flip flops and black and orange athletic gear. We’ve cut the timing a bit close, so my friend and I are frantically checking every single map on the path to East Pyne Hall, the site of our 12:30 class, English 222. The official course title is “Fanfiction: Transformative Works from Shakespeare to Sherlock” — essentially, a class I’d have given anything for as an undergrad.

To some extent, fanfiction has always had a place in the English classroom. The history of literature is one of reworking and retelling stories, especially prior to our modern conception of authorship. Popular media narratives often portray fan fiction — using someone else’s books, TV shows, films, or real-life personas, among other things, as the starting point for original fiction — as cringe-worthy scenes of sentimentality and/or sex between superheroes or vampires or all five members of a certain floppy-haired boy band. I and plenty of others have worked to ground the historically marginalized practice in “literary” precedent — favorite examples of authors explicitly refashioning others’ works include Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea and Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, both of which I first studied in a classroom.

To some extent, fanfiction has always had a place in the English classroom. The history of literature is one of reworking and retelling stories, especially prior to our modern conception of authorship. Popular media narratives often portray fan fiction — using someone else’s books, TV shows, films, or real-life personas, among other things, as the starting point for original fiction — as cringe-worthy scenes of sentimentality and/or sex between superheroes or vampires or all five members of a certain floppy-haired boy band. I and plenty of others have worked to ground the historically marginalized practice in “literary” precedent — favorite examples of authors explicitly refashioning others’ works include Jean Rhys’s Wide Sargasso Sea and Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, both of which I first studied in a classroom.

But fanfiction as we conceive of it today isn’t quite the same as Rhys tilting the focus of Jane Eyre to the “madwoman in the attic.” Modern fanfic practices are communal, with roots in mid-20th century sci-fi magazines. They’ve grown up through paper zines and collating parties to message boards and digital archives, fanfiction.net and LiveJournal, Archive of Our Own (AO3) and Tumblr and Wattpad. There are broad conventions that link the millions of people reading and writing fanfiction today (the vast majority of whom are wholly uncompensated for their hours of labor, enormous fanfic-to-traditional publishing deals like 50 Shades of Grey and After aside). Transformative fans share a language — tropes and kink memes and rec lists and OTPs — and in any given corner of fandom, stories talk to one another in fascinating ways.

But fanfiction as we conceive of it today isn’t quite the same as Rhys tilting the focus of Jane Eyre to the “madwoman in the attic.” Modern fanfic practices are communal, with roots in mid-20th century sci-fi magazines. They’ve grown up through paper zines and collating parties to message boards and digital archives, fanfiction.net and LiveJournal, Archive of Our Own (AO3) and Tumblr and Wattpad. There are broad conventions that link the millions of people reading and writing fanfiction today (the vast majority of whom are wholly uncompensated for their hours of labor, enormous fanfic-to-traditional publishing deals like 50 Shades of Grey and After aside). Transformative fans share a language — tropes and kink memes and rec lists and OTPs — and in any given corner of fandom, stories talk to one another in fascinating ways.

Fandom has a growing place in higher education: fan studies, a several-decades-old interdisciplinary field that focuses on fans and their practices, often sits within media studies or the social sciences. I had the privilege of attending the Fan Studies Network conference in London last autumn, where I heard a lot of interesting papers about people who really love stuff and the complicated ways they engage with that stuff. Fan scholars study fanfiction, certainly, but often with a focus on the communities that create it. Fanfiction as literature — reading and potentially critiquing living, (usually) amateur authors and the way they talk back to pop culture’s texts — is a relatively new prospect in the literature department. But as a former English major who furtively split her adolescent reading between Victorian novels and Harry Potter slashfic, reading fanfiction for credit would’ve been a dream come true.

My friend and I make it to the lecture hall just in time, and as we take our seats, the professor, Anne Jamison, makes introductions. She’s wearing a pair of leggings printed with the wallpaper from the living room of 221B Baker Street from the BBC’s Sherlock, complete with that yellow smiley face; I covet them deeply. I met Anne online, in the Sherlock fandom a little over a year ago, while I was trying to make sense of the furor surrounding Series 3. I read her book, Fic: Why Fanfiction Is Taking Over the World, flipped out over it, and interviewed her for a piece I wrote owning up to my fannish investment in the show. We met in-person in England last summer, and now I had the luck to be back across the Atlantic the semester she’d be visiting Princeton from the University of Utah. Even better, the semester she’d be teaching a class on fanfiction.

My friend and I make it to the lecture hall just in time, and as we take our seats, the professor, Anne Jamison, makes introductions. She’s wearing a pair of leggings printed with the wallpaper from the living room of 221B Baker Street from the BBC’s Sherlock, complete with that yellow smiley face; I covet them deeply. I met Anne online, in the Sherlock fandom a little over a year ago, while I was trying to make sense of the furor surrounding Series 3. I read her book, Fic: Why Fanfiction Is Taking Over the World, flipped out over it, and interviewed her for a piece I wrote owning up to my fannish investment in the show. We met in-person in England last summer, and now I had the luck to be back across the Atlantic the semester she’d be visiting Princeton from the University of Utah. Even better, the semester she’d be teaching a class on fanfiction.

“I first got interested in online fan culture because of teaching,” Jamison told me. “I was fascinated by the kinds of in-depth close readings and debates I saw fans of Buffy doing online, and they seemed to find it fun. I wanted my students to think being smart and critical could be fun, so I paid attention.” If you’ve ever spent an afternoon writing a 2,000-word close reading (in fandom, you’d call it a “meta”) of a TV show “for fun,” you definitely understand. The boards led Jamison to fanfiction, and she was struck by the ways that fic writers were engaging with the source material. “I’m eager for students to see creative work and critical work as interrelated,” she said. “I incorporated creative assignments in literature and theory classes long before I’d ever heard of fanfiction, so it was very natural to include fanfiction as part of curriculum.”

The cynical side of me expected to hear that a fanfiction class in an Ivy League English department would’ve been met with criticism from the old guard — walking down the halls of my college English department a decade ago, you’d regularly hear a typewriter clacking away, and I’m pretty sure it wasn’t being used to pen fanfic. But she hasn’t encountered professional backlash at Princeton or back home in Utah. “I’m sure there are people who think that but they haven’t told me about it — not my colleagues,” she said. “I get more pushback on YA and, frankly, on Victorian women’s poetry than I do on fanfic. Nothing can match the snideness with which male scholars of modernism tend to regard Victorian poetry by women.” But she stressed that she’s a tenured professor, a luxury that some fan studies scholars, many of whom are independent, aren’t afforded. “It gives me a kind of intellectual and professional freedom that is quickly disappearing.”

Jamison isn’t teaching this particular session of English 222: the guest lecturer is Dr. Lori Hitchcock Morimoto, a fan studies scholar who has come up from Virginia to talk about her area of expertise, transnational fandom, in which she asks questions like, “What happens when people from one place or culture become fans of something from another — especially if that thing already has a robust local fan culture?” I see these inquires daily on her Tumblr with the tag “transnational fandom FTW” — Morimoto is another Sherlock friend and I’ve spent the past year relying on her for nuanced global perspectives of the show, and of fandom and cultural consumption more broadly. There’s no one else on the Internet I’d turn to to analyze Benedict Cumberbatch in a kimono, which is about as high a compliment as I can bestow.

Morimoto grounds this particular lesson in the personal, describing moving from the U.S. to Hong Kong at a young age and being exposed to Western pop culture through the lens of East Asian media. She’s set the class critical texts as well as some fanfiction, specifically a crossover that puts Hong Kong star Leslie Cheung in the fictionalized world of the Japanese story Onmyouji. After the lecture the students split and attend discussion sessions — precepts, in Princeton lingo — and the conversation ranges from revisiting last week’s topic (bronies) to the new reading and issues surrounding clashing cultural perspectives in fandom.

Jamison skillfully manages the exchange, pushing in the right places and sitting back in others. Later she tells me, “It is a very diverse class in all kinds of ways — from ethnic background to major to level of prior fanfic experience, from people who grew up in Harry Potter fandom to people who had never read a fic before. So far everyone has found something to interest them or is doing a great job faking it.” On the day that my friend and I sit in, no one seems to be faking it, because the level of interest is clearly on display: the students are spirited and engaged, and it’s heartening to hear everyone talk about fandom and fanfiction the way they’d talk about broad themes in literature, or about any one traditionally published novel.

But fanfiction is not a traditionally published novel, and bringing it into the classroom offers up some new and challenging prospects. To understand these challenges, it helps to know a bit about the dynamics that have governed a lot of fanfiction communities over the past few decades, particularly as they became increasingly visible online. In the early days of online fandom, rights holders — the authors and corporations that owned the characters people were playing with — had a lot less understanding of (and patience for) fanfiction: Harry Potter fic archives, for example, were getting cease-and-desist letters from Warner Brothers for copyright infringement. Many authors were careful to brand their stories with legal(ish) disclaimers, something like, “This work is for fun, not for profit, and I own none of these characters.”

This conversation has shifted drastically in the past five years: many media corporations encourage fandom — after all, fans are a guaranteed enthusiastic audience for your product — but the monetization of some fan works has made the whole prospect trickier, usually hashed out on a case-by-case basis. Stephenie Meyer has sanctioned E. L. James, but plenty of writers, notably George R. R. Martin and Anne Rice, still speak out strongly against fanfiction. (Or Diana Gabaldon, the author of the Outlander series, who has sort of confusingly compared fanfiction to such things as “someone selling your children into white slavery” and “seducing” her husband.)

Because of legal concerns and the broader negative perceptions of the practice, the vast majority of fanfic writers use pseudonyms. I have read stories of people losing jobs when bosses discovered they wrote fanfiction; in Fic, a contributor describes her interest in Twilight fanfiction being used against her in divorce proceedings. The modern web is a less pseudonymous place than it was even five years ago, and some of this has bled over into online fandom, but pseudonyms still reign. Fanfiction is becoming increasingly exposed in the mainstream media, from the deeply positive — Rainbow Rowell’s Fangirl, for example — to the deeply negative, like far too many instances of celebrities being asked to read fanfiction for comic effect. Every bad article written at the expense of “rabid” fangirls puts fans on the defensive, and rightly so. But it can make fanfiction writers, who write for fun and not for profit, protective of their practices and their privacy — something that’s virtually impossible to achieve when publicly posted on the web.

Because of legal concerns and the broader negative perceptions of the practice, the vast majority of fanfic writers use pseudonyms. I have read stories of people losing jobs when bosses discovered they wrote fanfiction; in Fic, a contributor describes her interest in Twilight fanfiction being used against her in divorce proceedings. The modern web is a less pseudonymous place than it was even five years ago, and some of this has bled over into online fandom, but pseudonyms still reign. Fanfiction is becoming increasingly exposed in the mainstream media, from the deeply positive — Rainbow Rowell’s Fangirl, for example — to the deeply negative, like far too many instances of celebrities being asked to read fanfiction for comic effect. Every bad article written at the expense of “rabid” fangirls puts fans on the defensive, and rightly so. But it can make fanfiction writers, who write for fun and not for profit, protective of their practices and their privacy — something that’s virtually impossible to achieve when publicly posted on the web.

No fanfiction writer wants to be mocked. But do any of them want to be taught in a university classroom? Common practice allows for fanfiction writers to ask for positive feedback only — “no flames, please” or “no concrit,” short for constructive criticism. But an academic setting is often a critical space. Jamison has thought a lot about this question: where she once asked fanfic writers for permission to teach their work, she usually doesn’t now, though she continues to give students strict guidelines for behavior towards these stories in the context of the class. “Part of the reason I stopped asking was because of strong feelings I have about what it means to enter the public sphere,” she told me. “And publish something — whether for money or not. I think the professional-amateur divide is important, but I don’t think amateur status absolves you from all accountability or public comment.” Her syllabi are carefully crafted — “I have never worked so hard on a syllabus,” she says — and she tries to stick to widely-known source material or works that can stand alone: much of the trick of fanfiction is getting the connections between the original and the remix, and without context, not all works hold up. Fandom is not necessarily populated with people angry or uncomfortable having their works taught: many of the authors Jamison features tell her they’re happy to wind up on her syllabus.

But there are plenty of people within fandom who believe fanfiction has no place in the classroom at all: to remove a work from its “intended” context and divorce it from a largely unwritten set of rules is a violation for many fan writers. A few weeks into the semester, another university-level fanfiction class sent shock waves through some corners of fandom — in many peoples’ view, it violated these rules. This class was 3,000 miles away, at the University of California Berkeley, in a student-run pass/fail course that initially asked participants to read fanfiction from a wide variety of sources and then leave constructive criticism — even when it wasn’t asked for or welcome.

The course was brought to broader attention by a fic writer named waldorph, one of the authors featured on the syllabus, when she noticed that her Star Trek story was receiving comments she later described as “bizarrely tone-deaf, condescending, rude, and more than that, completely out of step and touch with all fannish norms.” Waldorph wrote a Tumblr post and it spread rapidly — many people were outraged that these stories were being engaged with this way. “Fandom writes for fandom,” she told me later. “We write for ourselves and our friends, and I certainly don’t think to myself ‘how will this be reviewed by a litcrit class?’ when I hit ‘post’ on AO3…The reality is that the way fandom gets interacted with is changing. The best we can do is be kind to each other and support each other when something like being required reading happens.”

The fallout from the revelation was swift and quickly spiraled away from the point of origin. Some authors didn’t mind being on the syllabus, but some certainly did. And one unique facet of fan fiction — that students were commenting on these stories, thereby directly interacting with authors (who are regularly in conversation with their readers) — underscored a major source of tension. “Instead of me being in a situation where I become tangentially aware that my works are being used/quoted/whatever and me just laughing and shrugging it off,” she said, “they were coming into my space and interacting directly with me.” The students running and participating in this course were mostly fans themselves, but they didn’t adhere to the “no concrit” rule that waldorph and many other fan writers live by. “My philosophy in navigating fandom is: ‘don’t be a dick,’” she said. “Don’t leave a nasty comment, just back-button out. If you can’t be kind about something you’ve read, don’t engage with it, and certainly don’t make that person feel bad about the thing they worked on.”

For the professors teaching fanfiction and fandom, sorting out these boundaries presents an enormous professional and ideological challenge, but they resist an “us versus them” kind of dichotomy, something waldorph also worked against as she analyzed the situation. The Internet is built on confirmation bias: it is easier to see the like-minded than not, especially in a place like fandom, which can often serve as a retreat from the stresses of daily life or a place to make genuine connections based on shared interest alone. But it’s not a monolith, and that often gets lost in the discourse. “Fandom encompasses a real diversity of cultures,” Morimoto told me. “Cultures of social class, of gender, of sexuality, cultures of race, of language, of role…I think we do fandom a disservice by a singular emphasis on community.” Jamison echoed this idea when I asked her about the Berkeley course. “I think it is important to acknowledge that those were student instructors who were active in fandom and based on their experiences in fandom, they thought what they were doing was in keeping with fandom practice, from what I understand. There is no one ‘fandom.’”

Sometimes it’s hard for me, a long-time fanfiction reader who’s never been brave enough to post her own fix — and I have written thousands of words over the years — to wrap my head around the idea of fanfiction being a closed community that can’t stomach criticism. The broader Internet can be a scary place to send out your words. When my colleagues and I publish articles on the web, with open comment threads beneath them and links to Twitter accounts where anyone can direct attacks, we wade into the mire — but then, we do so with full knowledge of that mire. And I haven’t been brave enough to post that fic — fandom, our connections to the characters and stories we really, really love, can feel so personal. Fiction is deeply personal, too. I want to protect fanfiction from unwanted outside attention — and I want to sing its praises to the world.

In the vast sea of fanfiction, much of it obviously varying in quality, there is some extraordinary writing happening, stuff that belongs in a university classroom, side by side with the classics. It’s a genre that works in new and interesting ways, and it deserves to be studied in loving detail. Mainstream attention of fanfiction isn’t going to go away — and it’s quickly ceasing to be a punch line, something I could never have predicted even five years ago. It will be taught and studied in future classrooms across the country — the only question is how.

Image Credit: Flickr/kaffeeringe