Joshua Corey is a poet who wrote a novel that reads like a film. Beautiful Soul: An American Elegy is a poet’s novel, its poetic concision married to a cameralike-gaze to create what might be classified as an art-house film of a novel. A poet’s noir, if you will. The novel straddles two continents — traveling between America and Europe — and opens in present-day Chicago, with Ruth, a wife and young mother lying in bed, envisioning raindrops falling like letters onto her roof and neighboring roofs. These dreams give rise to the receipt of letters, sent by her dead mother, M, who had become terminally ill and went abroad to die. The letters prompt Ruth to hire an investigator to trace her mother’s footsteps through Europe, and dually unearths M’s past, intertwined with a third narrative, which involves a college-age M, not yet a mother, in Paris during May ’68.

The reception of Beautiful Soul book has been quiet yet emphatic. It was listed by Dennis Cooper as a favorite book of 2014, praised by Chris Higgs as one of “the most interesting and impressive books” he’s read of late, and championed by Laird Hunt who called its “push-pull between stunning language and inventive narrative” as “pure pleasure.” With three books of poetry under his belt, and a fourth, The Barons, released last year (only months after Beautiful Soul), Corey is certainly prolific. He has also co-edited, with G.C. Waldrep, The Arcardia Project, an anthology of postmodern pastoral poems, and acts as co-director of NOW Books, which publishes experimental, often hybrid, works. Our conversation here touches on the allure of the novel as form, Beautiful Soul’s cinematic quality, artist Joseph Beuys as lodestar, and the book’s feminism, with regard to Ruth’s struggle with identity, her mothering, and her elusive history.

The reception of Beautiful Soul book has been quiet yet emphatic. It was listed by Dennis Cooper as a favorite book of 2014, praised by Chris Higgs as one of “the most interesting and impressive books” he’s read of late, and championed by Laird Hunt who called its “push-pull between stunning language and inventive narrative” as “pure pleasure.” With three books of poetry under his belt, and a fourth, The Barons, released last year (only months after Beautiful Soul), Corey is certainly prolific. He has also co-edited, with G.C. Waldrep, The Arcardia Project, an anthology of postmodern pastoral poems, and acts as co-director of NOW Books, which publishes experimental, often hybrid, works. Our conversation here touches on the allure of the novel as form, Beautiful Soul’s cinematic quality, artist Joseph Beuys as lodestar, and the book’s feminism, with regard to Ruth’s struggle with identity, her mothering, and her elusive history.

The Millions: Reading Beautiful Soul is an unexpectedly filmic experience. The novel opens with a film’s beginning: “Black screen. A flicker,” and only then, “The letter.” There’s an awareness of the camera’s gaze, its angles and panning, and the third section set in Paris ’68 for me recalls Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Dreamers. In many ways, Beautiful Soul seems to give life to its own film within the book. Would you talk about the influence of film on this novel, and if in this way the novel for you supersedes film?

Joshua Corey: I really like that idea — “to give life to its own film within the book.” I’ve long been fascinated by film treatments and by the parts of screenplays that aren’t dialogue, which in effect personify or subjectify the position of the camera as a peculiar kind of “we:” we see the protagonist, we see her face in close-up, we see the establishing shot…Here again I wanted that sense of active involvement in the story — of the story creating itself or being created by and for the reader-viewer in front of her eyes. I also wanted to play with some cinematic tropes evocative of American noir, Italian Neorealism, and the French New Wave — the midcentury visual imagination.

It’s funny you mention Bertlolucci’s The Dreamers, which is a film I deliberately chose not to watch once I realized the imaginative territory that the novel was leading me toward — perhaps foolishly I didn’t want to be influenced, even though I was already being influenced by what surely was one of Bertolucci’s primary influences — [François] Truffaut’s Jules et Jim. I suppose it would be all right if I watched it now!

It’s funny you mention Bertlolucci’s The Dreamers, which is a film I deliberately chose not to watch once I realized the imaginative territory that the novel was leading me toward — perhaps foolishly I didn’t want to be influenced, even though I was already being influenced by what surely was one of Bertolucci’s primary influences — [François] Truffaut’s Jules et Jim. I suppose it would be all right if I watched it now!

I don’t think Beautiful Soul in any way “supersedes” film, but I truly love the idea of a novel that is somehow also a film, and I’m flattered that you think I might have accomplished that.

TM: As a poet, what was your attraction to the novel, and, specifically, to writing a novel that conceives of itself as a film?

JC: I love the old Henry James line describing 19th-century novels as “large, loose, baggy monsters.” He didn’t mean it as a compliment, but I like the idea of the novel as a kind of supergenre capable of absorbing any kind of text — poems, essays, table talk, drama. I never got over my first encounter with Ulysses, which gave me the idea that the novel was at least as appropriate a site for formal experimentation as poetry. But most novels aren’t Ulysses and the mechanics of plot and the market-driven expectations that drive most American novels (beginning, middle, end; conflict, resolution, redemption) kept me from attempting fiction for a long time. It wasn’t until I began to realize the possibility of a voice, in prose, that I became able to write what eventually revealed itself as a novel with characters, scenes, a plot, and all the rest. My poetry has always been highly voiced. I think the first-person monologue, a la [William] Shakespeare and [Robert] Browning, is the poetic mode that made fiction possible for me.

JC: I love the old Henry James line describing 19th-century novels as “large, loose, baggy monsters.” He didn’t mean it as a compliment, but I like the idea of the novel as a kind of supergenre capable of absorbing any kind of text — poems, essays, table talk, drama. I never got over my first encounter with Ulysses, which gave me the idea that the novel was at least as appropriate a site for formal experimentation as poetry. But most novels aren’t Ulysses and the mechanics of plot and the market-driven expectations that drive most American novels (beginning, middle, end; conflict, resolution, redemption) kept me from attempting fiction for a long time. It wasn’t until I began to realize the possibility of a voice, in prose, that I became able to write what eventually revealed itself as a novel with characters, scenes, a plot, and all the rest. My poetry has always been highly voiced. I think the first-person monologue, a la [William] Shakespeare and [Robert] Browning, is the poetic mode that made fiction possible for me.

I did want to stage a sort of confrontation between the novel and the cinematic. It’s become a cliché now to say that TV shows like The Wire and The Sopranos are to us what [Charles] Dickens and Anthony Trollope were to the Victorians. But as someone who was skeptical about fiction for a long time, I really did wonder what the novel as medium can accomplish — what is proper to it, most fully its own, in the age of the total image. I was surprised as I went on to rediscover some of the sturdier virtues of storytelling, and some of that material — particularly the May -68 stuff — was the most fun for me to write.

TM: Ruth, protagonist of Beautiful Soul, is a mother, daughter, wife, and seeker, who has placed her desires on the back burner to raise her daughter, and who is often referred to as “the new reader.” “New reader” implies that there is an “old reader,” too, and that difference between these categories are significant. While some of the implications of “new reader” are obvious to the narrative and to our times, the idea of the new reader seems to run even deeper. Would you talk more about Ruth, her identity as the “new reader,” and what this means?

JC: There are a couple of “old readers” in the book — most obviously Ruth’s mother, M, whom she remembers as a compulsive reader of “cozy” English mysteries, but there’s also Ruth’s husband Ben, who like so many of us no longer reads much of anything because he ends up being distracted by screens. But any sort of reader, old or new, is an investigator and interpreter. Ruth’s mother’s story prefigures Ruth’s: as the story unfolds we discover that she too is investigating the mysterious and inexplicable past of her parents, both Holocaust survivors. Her investigation fails; the success or failure of Ruth’s depends upon the powers of her imagination, her willingness to become a character in her own story rather than remaining outside of it (which is what the “beautiful soul” does in [Georg Wilhelm Friedrich] Hegel’s account of the progress of Spirit). The new reader is someone for whom reading is in question — whether in print or on a Kindle — for whom the experience of reading puts her identity into question. I think readers are heroic when they put themselves and their expectations of a text at risk.

TM: “Extimation” is deemed to be what Ruth needs, as a new reader, to connect to the rupture between her actions and her desire, which at one point manifests as the desire to lie carelessly in the grass with her daughter, but ignores it to play the role of the responsible mother. This is called “a flawless trap of a moment.” I’m curious about the idea of this trap, the roles characters fall into, or perhaps demand, as it’s asked, “Why do we insist on the narrative of our lives?” I’m also curious about this idea of extimacy, and why it’s what Ruth needs.

JC: This really goes back to the novel’s title, which practically begs to be misunderstood as sentimental. As I remarked before, it’s a term from Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit and refers to a subject whose stakes in his own innocence or purity are such that he insists on seeing evil, or experience, or history, or nature, or “the world,” as something “over there.” It’s a stance in perfect tension with noir, which I define as the narrative in which the subject finds herself part of and implicated in the dark territory she purports to investigate. [Jacques] Lacan’s term is another disruptor of this notion of an inside and outside that are sealed off from each other, when in fact the “outside world” is completely inside each one of us, and manifests as pathology precisely to the degree we are unable to acknowledge that. Ruth’s struggle to fully inhabit her various identities — as daughter, as mother, as mourner, as American, as reader, and as writer — produces the plot as well as the struggle with plot.

TM: Beautiful Soul has been called a feminist novel and seems to be very much about mothers and mothering, about origins, and the attempt to trace them. What drew you to write about mothering, and how this is tied to ideas of homeland and the domestic?

JC: I’m honored that it might be construed as a feminist novel. But the answer to this question is rooted in the personal: my mother wrote poetry, and spoke several languages, and in all ways inspired me to become a writer. She was also the daughter of a pair of Auschwitz survivors; she was born in Budapest in 1942, survived the war there, and then came to this country after a bleak interval in a displaced persons camp in Germany; all her life long she was haunted by these stubborn historical facts, and she never really had a career to suit her talents but lived out her days as a housewife in suburban New Jersey. She was a brilliant, funny, often depressed, sometimes bitter woman, and she died of cancer when I was 21, just as she seemed to be finding a new path for herself as a clinical social worker. I’ve never gotten over that loss, and the novel represents both an elegy for her (as indicated in the subtitle) and an imaginative investigation of the forces that shaped her and through her, me.

On another level, perhaps because I had such a strong mother figure, I’ve long been interested in the domestic drama or what they used to call in Hollywood the “woman’s picture”; [Virginia] Woolf and [Jane] Austen are two of my favorite novelists, and Henry James (who was passionately preoccupied with women’s lives) isn’t far behind. It seems to me that becoming a mother is a crisis in a woman’s life in a way that’s not very analogous to what happens with men; women are asked to identify with motherhood but the fathers I know are mostly just men with kids. I wanted to write a kind of domestic noir that would explore the strength and toughness of women, while puncturing a little bit the mythic invulnerability of masculinist figures like the detective or the revolutionary. I just saw the David Bowie show at the MCA, which reminds me of how strongly I am sometimes drawn to flamboyance and androgyny — not in my personal style, but in my writing.

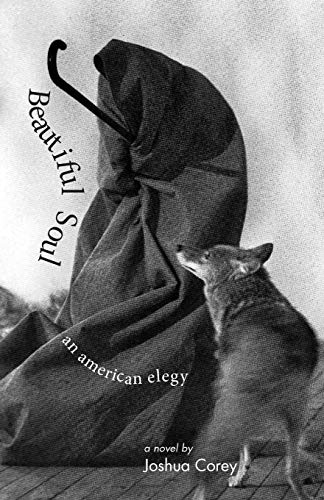

TM: Artist Joseph Beuys as shaman graces the cover of both Beautiful Soul and of your new book of poetry, The Barons. What’s Beuys’s influence on your work?

JC: Beuys fascinates me on a number of levels. First of all, there’s his situation as a charismatic German artist who served in the Luftwaffe, and whose entire subsequent career can be read as an atonement for or evasion of that history. There’s an amazing sound poem by the Fluxus artist Al Hansen (grandfather of Beck) that I discovered called “Joseph Beuys Stuka Dive Bomber Piece,” which imagines, in sputtering phonemes that very occasionally resolve themselves into words, Beuys flying his Stuka (a kind of dive bomber) during World War II — I pay homage to that piece with a transcription of what I hear in it in a poem in The Barons. Beuys was a pacifist and an environmental activist who at one time stood for a seat in the European Parliament as a member of the Green Party, nevertheless implicated in the greatest historical crime of his time. The art itself is an art of process and vulnerability; his totemic materials are animal fat and felt, “warm” rather than “cool” media for bizarre sculptures and performances that nonetheless carry with them aspects of the cozy and the cute. I was particularly drawn to the “America” performance, and wanted it for the cover of Beautiful Soul, because it’s a remarkable updating of Henry James’s “international” theme, the collision of innocent America with decadent experienced Europe. Wrapped in folds of felt, wielding a kind of magic staff reminiscent, yes, of a shepherd’s crook but also of vaudeville and the Sally Bowles of Cabaret, Beuys the shaman from Europe confronts the American coyote, which suggests wildness but also something of a trickster quality. You can’t see Beuys’s face in the image and yet it’s enormously expressive in its mystery. It puts the “American” in “American Elegy” into question, I think, since the loss of American innocence is perhaps devoutly to be wished instead of mourned.

TM: With images of Beuys gracing both books’ covers (and with both published this year) it leads me to ask, are they born from similar sources of inspiration, or are they entirely distinct?

JC: Beuys on both covers is a kind of Easter egg for those who might actually follow my work closely enough to read both books! And they both feature animals, don’t they; a coyote for Beautiful Soul and a white horse for The Barons. But the differences between the two images maybe suggest what’s different about the two books as well, which might be summarized this way: the novel is about the past, the poetry is about the present or maybe the future. The image on the cover of The Barons is a diptych from a 1969 performance of “Iphigenie / Titus Andronicus” in which Beuys appeared on a Frankfurt stage in a fur coat with a horse behind him. Beuys uttered various sounds and guttural cries during the performance, but also snatches of dialogue from Shakespeare’s play, his most lurid, and Goethe’s Iphigenia in Taurus — in an interview Beuys remarked, “I thought it was time to handle language the way I had previously handled felt.” Both plays featured endangered young women, victimized by their fathers’ blindness: Iphigenia is sacrificed by her father for the sake of going to war, while Lavinia is raped and has her hands cut off and her tongue cut out by two brothers whose other brothers were killed in ritual sacrifice by Lavinia’s father, Titus. The notion of unnatural sacrifice, particularly of the innocent, resonated with me as a dark image of our historical moment, not only of the endless war footing we’ve been on since 9/11 but our insane war against the earth itself. But there’s a ray of hope in Goethe’s reworking of the Iphigenia story: in his play Iphigenia was saved from death and is now a priestess of Diana who must battle against the ancient custom of human sacrifice. The diptych itself is striking: on top we see Beuys kneeling in contemplation or discouragement while the horse — a symbol of the threatened earth as well perhaps of ancient notions of chivalry — crops straw in the background. On the bottom, in a brilliant negative image, we see a standing Beuys holding a pair cymbals — an image of resonance. The poems of The Barons enact a similar dialectic between despair and music, the percussion of language and the absurd particulars of modern life.

Most of the poems were written before I wrote the novel, but there are some interesting gestures there toward narrative, including a poem that’s titled, “The Novel.”

TM: John Ashbery says that with The Barons, you have “reinvented the good old-fashioned American avant-garde epic poem (Whitman, Stein, Crane, O’Hara) and thrust it, kicking if not screaming, into the early 21st century.” Your preceding book of poetry, Severance Songs, deconstructed the sonnet. With each book of poetry, do you attempt a different experiment with form?

TM: John Ashbery says that with The Barons, you have “reinvented the good old-fashioned American avant-garde epic poem (Whitman, Stein, Crane, O’Hara) and thrust it, kicking if not screaming, into the early 21st century.” Your preceding book of poetry, Severance Songs, deconstructed the sonnet. With each book of poetry, do you attempt a different experiment with form?

JC: I’m a formalist at heart, in the sense that I have always been fascinated by the material-historical properties of words — their sonic qualities, their viscosity, their etymologies — and the ways in which both traditional and open forms pattern those properties and work on a reader’s nervous system a beat or three before semantic cognition kicks in. The sonnet is a constant temptation to a poet because it’s brief enough and graceful enough in its structure to suggest that perfection might be possible. At the same time, I’m suspicious of purity and so I wanted in Severance Songs to dirty up the sonnet, to work both in and against the grain of the form. The Barons harkens back to my first book, Selah, in being various formally: there’s a long quasi-epic poem about post-9/11 New York, Compostition Marble, which is where I think the Crane and Whitman comes in; there are prose poems, brief lyrics, visionary Ginsbergesque rants, you name it. One of the poems, “It Goes by in Flashes, It Bows” was partly based on conversations overheard while riding the Metra here in Chicago; I like to think of the different forms as drawing upon or drawing out some of the confused and angry and deadpan voices of all of us living in the hurtling doomstruck world that the titular barons have made.

TM: Beautiful Soul seems to embrace an idea of the multiplicity of the self, of the I, of fragmentation of identity, while at the same time, Ruth yearns to define her unique identity, to be distinct. Would you talk more about this idea of identity in relation to ancestry, and the tension this brings?

JC: This is another angle on the “extimacy” question: the desire to be an autonomous self versus the desire to be part of something larger or something other, whether that something be a family, a lineage, an ethnic group or religion (in this case Jews and Judaism), or European history. Ruth is unsurprisingly ambivalent: I think she knows that some kind of pure identity as beautiful soul is not a realistic option for her, but at the same time she feels overwhelmed by what her mother represents, both as formidable personality and as representative of a historical experience that resonates in Ruth’s life, but that she is powerless to change — that was never really hers. That’s why she dreams up Lamb, the P.I., a kind of animus who will do the dirty work of integrating the wound of M (M is W upside-down; a Beuysian motto is “Show your wound”) into Ruth’s self without her having to compromise her own integrity. Of course it’s not that easy; it’s more than any dream can do. Ruth has to open herself to otherness — and as is so often the case, it’s the otherness that’s closest to us that she finds the most threatening.

TM: Ruth is literally haunted by her past and yet she hires an investigator to seek out information about her mother’s demise and her father, too, as if knowledge will bring resolution. What is the allure of uncovering facts, and are facts always elusive, like M herself?

JC: Again, it’s a question of integration. We in America are poor in history compared to Europe; Ruth’s investigation by proxy is an attempt to appropriate some of that history for herself (and what could be more American that that?). But history resists her: the core historical experience that affects her, Auschwitz, cannot be narrated without repeating the atrocity. The secondary history, that of the ’60s (compressed for reasons of expedience into Paris ’68, though earlier drafts also had storylines set in early-’70s New York and in a university on the brink of the theory wars of the ’80s), can be narrated and is in the voice of Gustave, the former art student who may or may not be Ruth’s biological father. And yet hearing this story brings Ruth no closer to understanding her mother as her mother; it only reveals something of her as a person, which to a child is no help. Among other things Ruth must surrender her child’s position if she is to be reconciled with her mother’s ghost. Does she, can she succeed? I think it’s left up to the reader.