For more than half a century, the struggle for civil rights in America has provided a volcano of inspiration for all sorts of writers. The flow of words started with eyewitness reports from the front lines of the battlefield — Montgomery, Little Rock, Greensboro, Nashville, Anniston, Jackson, Birmingham, Selma — written by some brave and dedicated journalists, black and white. It soon grew into a river of books – memoirs, biographies, reportage, histories, autobiographies. Eventually filmmakers followed the lead of these writers, and their labors, both documentaries and features, have finally stepped into the spotlight with this year’s Best Picture Oscar nomination for Selma, the story of Martin Luther King Jr.’s role in the bloody Selma-to-Montgomery march that led to passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Win or lose on Oscar night, Selma has already performed a valuable service. Along with critical kudos and box office success, it has inspired loud dismay that its black lead actor, David Oyelowo, and its black director, Ava DuVernay, were snubbed by the Oscars — and, beyond that, that there are no persons of color in the Best Actor, Best Actress, or Best Director categories. For good measure, loyalists of President Lyndon B. Johnson have howled that Selma paints him, unfairly, as a reluctant advocate of the Voting Rights Act.

Win or lose on Oscar night, Selma has already performed a valuable service. Along with critical kudos and box office success, it has inspired loud dismay that its black lead actor, David Oyelowo, and its black director, Ava DuVernay, were snubbed by the Oscars — and, beyond that, that there are no persons of color in the Best Actor, Best Actress, or Best Director categories. For good measure, loyalists of President Lyndon B. Johnson have howled that Selma paints him, unfairly, as a reluctant advocate of the Voting Rights Act.

While this storm has been fascinating to watch — or infuriating, depending on your point of view — it should not come as a surprise. The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences is, after all, still very much a boy’s club — make that a white boy’s club or, better yet, an old white boy’s club. The Academy is more than 90 percent white, men outnumber women three to one, and the members’ average age is 63. The five movies in the Best Adapted Screenplay category are a telling reflection of this club’s makeup: each one is a portrait of an extraordinary gentleman — a civil rights leader, a sniper, a mathematician, a cosmologist, and a drummer. Not a woman in the pack.

The uproar over this year’s monochromatic and heavily masculine Oscar nominations threatens to obscure an important fact: Selma may be an artistic astonishment, but it did not come out of nowhere; it is the climax of a cinematic crescendo that has been building for years.

The civil rights movement’s long journey to Oscar recognition began in the 1970s, when Ernest J. Gaines’s novel The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman inspired a TV movie of the same name, the story of a remarkable woman who was born into slavery and lived to 110, long enough to join the civil rights movement in the 1960s. The movie, starring Cicely Tyson, was a breakthrough for American television, putting civil rights activists front and center and treating them with sympathy and respect. (Feature films were by then slightly more accommodating to black characters, especially if they were played by Sidney Poitier.) The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman was followed by King, a TV mini-series based on the life of Martin Luther King Jr., and Eyes on the Prize, Henry Hampton’s decorated 14-hour documentary of the civil rights movement. Such movies about the movement set a high standard, one that many later filmmakers would fail to meet.

The civil rights movement’s long journey to Oscar recognition began in the 1970s, when Ernest J. Gaines’s novel The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman inspired a TV movie of the same name, the story of a remarkable woman who was born into slavery and lived to 110, long enough to join the civil rights movement in the 1960s. The movie, starring Cicely Tyson, was a breakthrough for American television, putting civil rights activists front and center and treating them with sympathy and respect. (Feature films were by then slightly more accommodating to black characters, especially if they were played by Sidney Poitier.) The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman was followed by King, a TV mini-series based on the life of Martin Luther King Jr., and Eyes on the Prize, Henry Hampton’s decorated 14-hour documentary of the civil rights movement. Such movies about the movement set a high standard, one that many later filmmakers would fail to meet.

A prime example of such a failure — and a prelude to this year’s dust-up over the immaculate whiteness of various Oscar categories — was the director Alan Parker’s 1988 feature film, Mississippi Burning, which received seven Oscar nominations but little love from black critics or audiences. The movie focuses on a pair of mismatched white FBI agents — one played by Gene Hackman as a gruff former Mississippi sheriff, the other by Willem Dafoe as a gung-ho young Yankee — who are sent in to solve the disappearance of three civil rights workers during the Freedom Summer of 1964. The two agents spar at first but eventually work together and close the case. In addition to pushing the black characters deep into the shade — a source of much anger at the time — Mississippi Burning posits that J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI was a protector of civil rights activists. Nothing was further from the truth, as Selma points out, and as Brent Staples noted in The New York Times shortly after Mississippi Burning was released.

A prime example of such a failure — and a prelude to this year’s dust-up over the immaculate whiteness of various Oscar categories — was the director Alan Parker’s 1988 feature film, Mississippi Burning, which received seven Oscar nominations but little love from black critics or audiences. The movie focuses on a pair of mismatched white FBI agents — one played by Gene Hackman as a gruff former Mississippi sheriff, the other by Willem Dafoe as a gung-ho young Yankee — who are sent in to solve the disappearance of three civil rights workers during the Freedom Summer of 1964. The two agents spar at first but eventually work together and close the case. In addition to pushing the black characters deep into the shade — a source of much anger at the time — Mississippi Burning posits that J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI was a protector of civil rights activists. Nothing was further from the truth, as Selma points out, and as Brent Staples noted in The New York Times shortly after Mississippi Burning was released.

“The Hoover FBI was not, as Mr. Parker suggests, made up of jaunty, sympathetic types, who bit their nails bloody over civil rights deaths,” Staples wrote. “Hoover was decidedly hostile to such investigations, thought the movement was a Communist conspiracy and went after civil rights violations so slowly that he often came near openly defying the President and Attorney General.” Parker has defended casting two white actors in the lead roles because, as a simple matter of fact, there were no black FBI agents in 1964. But conspicuously absent from the movie, as Staples, noted, were dedicated black activists who were in Mississippi at the time, including Robert Moses, John Lewis, and Fannie Lou Hamer.

Movies about the civil rights movement — the successful ones– have tended to follow one of two strategies. They focus either on the well-known leaders or on the faceless foot soldiers — or, for lack of better terms, on the “big” people or the “little” people. In the former category are movies about King, Malcolm X, Rosa Parks, Medgar Evers, James Meredith, and the Tuskegee Airmen; in the latter category are movies about the students who integrated Central High School in Little Rock, the students who sat in at the Woolworth’s lunch counter in Greensboro, the Freedom Riders, the participants in Freedom Summer, the journalists who covered these events, members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, also known as SNCC and pronounced Snick, including Robert Moses, Diane Nash, and James Bevel.

Among its many virtues is the way Selma deftly straddles this line, putting King at center stage but surrounding him with supporters and antagonists, both black and white, both famous and unknown. The movie even dramatizes the often-overlooked fact that King faced opposition from within the movement, as when disgruntled SNCC students accuse him of selling out for refusing to lead the way across Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge on the second of three tries, the so-called “Turnaround Tuesday” that followed horrific “Bloody Sunday.”

One filmmaker who has built a stellar career making documentaries about the movement’s “little” people is Stanley Nelson, who has produced vivid portraits of unsung journalists (The Black Press: Soldiers Without Swords, 1999); a teenage murder victim (The Murder of Emmett Till, 2003); courageous barrier breakers (Freedom Riders, 2010); and the fateful summer of 1964 (Freedom Summer, 2014).

“I’m interested in the people behind the big figures,” Nelson said by telephone from Park City, Utah, where his new documentary, Black Panthers: Vanguard of a Revolution, was having its premier at the Sundance Film Festival. “We learn about Martin Luther King and Malcolm X and Rosa Parks in school. But what would motivate somebody who lives in Selma to become a part of the march to Montgomery? That’s what interests me — the people behind the scenes.”

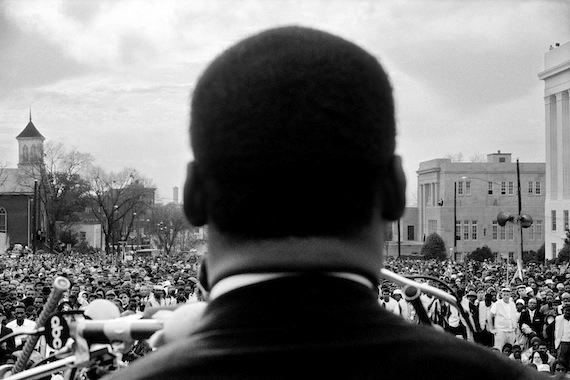

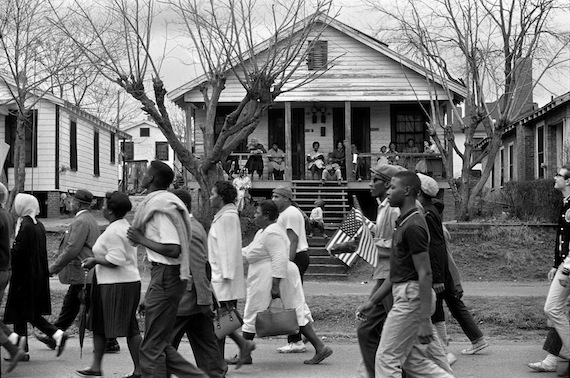

Another fascinating glimpse of the people behind the scenes is on display now at the New York Historical Society, in a show called “Freedom Journey 1965.” It consists of photographs, mostly black and white, taken by a New York college student named Stephen Somerstein, who walked the 54 miles from Selma to Montgomery and chronicled the marchers, spectators, and police he encountered along the way. The show is a knockout. We see the “big” people — King, Joan Baez, James Baldwin, Harry Belafonte — and, better yet, we also see the “little people,” including black women on porches with their babies, white hecklers, rapt families watching from the side of the road, and many of the 25,000 people who get swept up in the euphoric spirit of the march. (For more photo-documentation of this and other civil rights marches, see Dan Budnik’s splendid book, Marching to the Freedom Dream.)

Nelson has high praise for Selma. He says he was especially impressed by the way Oyelowo “channeled” King — as opposed to the way Jamie Foxx “imitated” Ray Charles in Ray. Nelson found the portrayal of an ambivalent LBJ “brilliant,” and he was delighted that DuVernay brought out the internecine friction between King and SNCC.

In the end, the filmmaker in Nelson sees virtues in Selma that have as much to do with craft as with race. The movie, he says, “has shown that you can make a film that looks good on a fairly limited budget. And it has shown that if you make a good film, people will come.”

In this contentious Oscar season, that may be the most uplifting news of all.

Image Credit: The New York Historical Society.