Last year, as we noted here, the source material in the Oscar category for Best Adapted Screenplay was immaculately fiction-free. All five screenwriters looked elsewhere for inspiration — to memoirs, investigative journalism, reportage, and, weirdly, to an earlier screenplay which, under the arcane rules of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, qualifies as “previously published or produced material.” I’ve said it before but I’ll say it again: that last nomination was a little too inside-baseball for me. But don’t forget, we’re dealing with Hollywood here.

Before last year’s Oscar went to John Ridley for his adaptation of Solomon North’s memoir, 12 Years a Slave, I suggested that the writers of adapted screenplays needed to start mixing a little fiction into their reading diets. In 2014, I’m happy to report, they did. A very little. A grand total of one of this year’s five finalists for Best Adapted Screenplay drew on a work of fiction.

It wasn’t always this way. As recently as 1998, all five Best Adapted Screenplay nominees were inspired by novels. (The statue that year went to Bill Condon for Gods and Monsters, based on Christopher Bram’s novel, Father of Frankenstein.) Through the years, the scripts of Oscar-winning movies have been based on novels by a gaudy galaxy of literary talents, including Jane Austen, Colette, Jules Verne, Henry Fielding, J.R.R. Tolkien, Sinclair Lewis, Harper Lee, E.M. Forster, Robert Penn Warren, Larry McMurtry, Mario Puzo, Ken Kesey, Michael Ondaatje, and Cormac McCarthy.

But the novel is now in retreat — and not only in Hollywood — as screenwriters and moviegoers turn their gaze to movies based on established franchises, comic books, graphic novels, musicals, non-fiction books and magazine articles, TV shows, memoirs, and biographies. There’s nothing inherently wrong, or particularly new, about such source material. Screenwriters have been adapting scripts from comic books at least since 1930, and filmmakers have always favored a “true” story (or, better, yet something “based on a true story”) over fictional stories. That’s because “true” stories are easier to write, make, and sell. I would argue that they’re also less likely to amaze than stories that come from a gifted novelist’s imagination.

So I say fiction lovers should rejoice that this year Hollywood is paying homage to something — to anything — produced by a novelist. It doesn’t happen every day (or, obviously, every year), and it’s becoming increasingly rare as Hollywood continues to play it safe while trying to connect with an audience that’s less and less likely to read serious fiction.

This year’s finalists for Best Adapted Screenplay are:

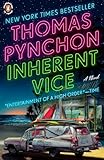

Inherent Vice

The writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson based his script on Thomas Pynchon’s 2009 novel of the same name. Purists could argue that Anderson has settled for Pynchon Lite instead of the heavy goods (Gravity’s Rainbow, say, or V., or even Mason & Dixon). Let’s not quibble. Anderson has streamlined Pynchon’s novel while remaining true to its spirit, which is the essence of a successful adaptation. We get a fine facsimile of Pynchon’s wake-and-bake private eye, Doc Sportello, played with zest by Joaquin Phoenix in sandals and sizzling muttonchops. Doc’s search for a missing real-estate developer takes him through a post-Helter Skelter L.A. labyrinth of surfers, hustlers, dopers, and other less benign parties. It may be Pynchon Lite, but I’ll take it any day over Toy Story 13.

The writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson based his script on Thomas Pynchon’s 2009 novel of the same name. Purists could argue that Anderson has settled for Pynchon Lite instead of the heavy goods (Gravity’s Rainbow, say, or V., or even Mason & Dixon). Let’s not quibble. Anderson has streamlined Pynchon’s novel while remaining true to its spirit, which is the essence of a successful adaptation. We get a fine facsimile of Pynchon’s wake-and-bake private eye, Doc Sportello, played with zest by Joaquin Phoenix in sandals and sizzling muttonchops. Doc’s search for a missing real-estate developer takes him through a post-Helter Skelter L.A. labyrinth of surfers, hustlers, dopers, and other less benign parties. It may be Pynchon Lite, but I’ll take it any day over Toy Story 13.

American Sniper

“I couldn’t give a fuck about the Iraqis,” Chris Kyle wrote in American Sniper: The Autobiography of the Most Lethal Sniper in U.S. History (with ghostwriters Jim DeFelice and Scott McEwan). “I hate the damn savages.”

“I couldn’t give a fuck about the Iraqis,” Chris Kyle wrote in American Sniper: The Autobiography of the Most Lethal Sniper in U.S. History (with ghostwriters Jim DeFelice and Scott McEwan). “I hate the damn savages.”

The screenwriter Jason Hall captured Kyle’s machismo and his Manichean worldview in his screenplay for American Sniper, which found the ideal director in Clint Eastwood, no stranger to the notion that evil is at large in the world and it’s the duty of good men to use any means, including deadly force, to crush it. Kyle claimed to have killed more than 250 people during four tours of duty as a Navy SEAL sniper in Iraq (160 are confirmed), and he was not inclined to apologize for his work — or even ponder its moral ambiguities. Neither was Eastwood. Kyle was shot dead at a Texas gun range by a fellow veteran in 2013. American Sniper has taken in $250 million so far at the box office, and it has further divided a country already deeply divided over our forever wars. Michael Moore hated the movie; Sarah Palin loved it.

The Imitation Game

The screenplay for The Imitation Game is the least faithful to its source material of this year’s nominees — and therefore probably a lock to take home the Oscar. Graham Moore’s script was adapted from Alan Turing: The Enigma, a biography of the brilliant British mathematician Alan Turing, written by the brilliant British mathematician and gay rights activist Andrew Hodges. In telling the story of Turing’s heroic work breaking World War II German codes, Moore and director Morten Tyldum have gone the predictable Hollywood route, turning Turing into an ur-nerd, which he was not, and making him dapper, which he was not. (Turing, according to Hodges, was eccentric but likeable, and a bit of a slob.) But this is Hollywood, and so Turing, as played by the mesmerizing Benedict Cumberbatch (who is up for a Best Actor Oscar), is turned into a cartoon: he’s the heroic gay misfit struggling against an uptight homophobic society. The movie ends on this note: “After a year of government-mandated hormonal therapy, Alan Turing committed suicide in 1954.” There is, however, no conclusive evidence that Turing committed suicide, and much ongoing speculation that he died accidentally, or even was murdered. But this is Hollywood, where complexity must never get in the way of a good cartoon.

The screenplay for The Imitation Game is the least faithful to its source material of this year’s nominees — and therefore probably a lock to take home the Oscar. Graham Moore’s script was adapted from Alan Turing: The Enigma, a biography of the brilliant British mathematician Alan Turing, written by the brilliant British mathematician and gay rights activist Andrew Hodges. In telling the story of Turing’s heroic work breaking World War II German codes, Moore and director Morten Tyldum have gone the predictable Hollywood route, turning Turing into an ur-nerd, which he was not, and making him dapper, which he was not. (Turing, according to Hodges, was eccentric but likeable, and a bit of a slob.) But this is Hollywood, and so Turing, as played by the mesmerizing Benedict Cumberbatch (who is up for a Best Actor Oscar), is turned into a cartoon: he’s the heroic gay misfit struggling against an uptight homophobic society. The movie ends on this note: “After a year of government-mandated hormonal therapy, Alan Turing committed suicide in 1954.” There is, however, no conclusive evidence that Turing committed suicide, and much ongoing speculation that he died accidentally, or even was murdered. But this is Hollywood, where complexity must never get in the way of a good cartoon.

The Theory of Everything

Stephen Hawking’s first wife, Jane Wilde Hawking, wrote a queasy memoir about the joys and trials of being married to an award-winning cosmologist who suffers from debilitating amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. That book, Travelling to Infinity: My Life With Stephen, became the basis for Anthony McCarten’s screenplay for The Theory of Everything, which tells the story of the couple getting married, raising three children, separating, marrying other partners, and somehow remaining close through it all. Felicity Jones, who got an Oscar nomination for her portrayal of Jane, told an interviewer, “That’s why I love Jane and Stephen, because they seem like very English, uptight, repressed people from afar. But as you get closer, they’re these extraordinary bohemians, these people who have adapted and changed and lived a very unusual life.”

Stephen Hawking’s first wife, Jane Wilde Hawking, wrote a queasy memoir about the joys and trials of being married to an award-winning cosmologist who suffers from debilitating amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. That book, Travelling to Infinity: My Life With Stephen, became the basis for Anthony McCarten’s screenplay for The Theory of Everything, which tells the story of the couple getting married, raising three children, separating, marrying other partners, and somehow remaining close through it all. Felicity Jones, who got an Oscar nomination for her portrayal of Jane, told an interviewer, “That’s why I love Jane and Stephen, because they seem like very English, uptight, repressed people from afar. But as you get closer, they’re these extraordinary bohemians, these people who have adapted and changed and lived a very unusual life.”

Whiplash

Last year the controversy was over Before Midnight, writer-director Richard Linklater’s third installment in the ongoing romance of another pair of extraordinary bohemians. The screenplay, written by Linklater and his stars, Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke, qualified as adapted because it was based on the earlier screenplays.

Last year the controversy was over Before Midnight, writer-director Richard Linklater’s third installment in the ongoing romance of another pair of extraordinary bohemians. The screenplay, written by Linklater and his stars, Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke, qualified as adapted because it was based on the earlier screenplays.

This year the controversy belongs to Whiplash, written and directed by Damien Chazelle, which tells the story of an aspiring drummer and his fanatical, abusive teacher. Back in 2013, in an effort to raise money for the project, Chazelle showed an 18-minute segment of the unfinished film at Sundance, where it won the prize for Best Short Film. The prize attracted money, and last year the completed, 107-minute feature won the Grand Prize at Sundance. The Writers Guild of America designated the script “original;” but based on its metamorphosis from short to feature, the Academy placed in the “adapted” category. Call the screenplay what you will, this shoestring movie, shot in just 19 days, has been nominated for a stunning five Oscars, including Best Picture. If you’re fond of Cinderella stories, this one’s for you.

Which brings us back to novels and screenplays. Four of this year’s eight nominees for Best Picture are based on adapted screenplays. The only adapted screenplay that didn’t also get the nod for Best Picture was the one based on — you guessed it — a novel by Thomas Pynchon.

Image Credit: Flickr/Prayitno