1.

During summer break, sophomore year, my father and I took a short trip from our house on Sugarbush Drive (memorable streetname, unmemorable neighborhood) to visit the Jack Kerouac House. It was a 20 minute drive down I-4 to the small quaint house that is now situated a few blocks from a sprawling commercial development. Orlando was an agreeable town when Kerouac’s mother moved there, and while Kerouac wrote The Dharma Bums there. A few years later, the arrival of the Walt Disney Corporation would radically alter the landscape, physically and culturally.

We walked around the House and knocked on the door. Answering the door was an early-career MFA graduate, the House’s resident writing fellow. The three-month fellowship ostensibly afforded him the time to work on a play about a New Orleans jazz musician. A pair of sunglasses slid down his nose, exposing his puffy eyes: he was just then emerging from a hangover. Work, he explained, was going slowly.

We walked around the House and knocked on the door. Answering the door was an early-career MFA graduate, the House’s resident writing fellow. The three-month fellowship ostensibly afforded him the time to work on a play about a New Orleans jazz musician. A pair of sunglasses slid down his nose, exposing his puffy eyes: he was just then emerging from a hangover. Work, he explained, was going slowly.

When we asked for details about the House and Kerouac, the playwright politely pointed us to a neighbor, a retiree who was walking across the street. The pensioner claimed to have known Kerouac’s mother, who had actually owned the house, as well as Kerouac. She kept “a nice lawn” and “was a sweet woman,” but he was “a drunk” and a “druggy.” Whether or not it was true was beside the point. My father and I agreed the Orlando Tourism Board couldn’t have dreamed up a better touch of embellished authenticity than a curmudgeonly, fist-waving, stay-off-my-lawn Floridian to America’s Own Free-Love Dionysus. Granted, a residence of a 20th-century American novelist probably never earned much notice in the Tragic Kingdom.

Years after visiting the Kerouac House, during a vacation in Prague, I visited Bohumil Hrabal’s cherished pub, U zlatého tygra (At the Golden Tiger). He once shared a drink with Bill Clinton and Vaclav Havel in the same boisterous, salty, regulars’ bar. At one of the shared tables in the backroom, I met a half-British, half-Czech jazz singer who boasted that he played cards with Hrabal’s frequent collaborator, the film director Jiří Menzel (Closely Watched Trains, Larks on a String). According to the singer, who can be found performing a fine version of “Strange Fruit” on the west bank of the Charles River most nights, Menzel was the worst director of live opera in history and, at 75, an incorrigible womanizer. The latter, at least, was meant as high praise.

These are examples in my long-held fascination with writer lore and the places they immortalized. It probably began, at eight, when I first checked out the collected short stories of Edgar Allan Poe from the Poplarville Public Library, and read the short, breathless biography in the introduction (Virginia Clemm, alcoholism, his vexed relationship with a father figure). Since, I have sabotaged dates, relationships, other people’s vacation plans, among other things, for a few extra hours in the Eudora Welty House, Rowan Oak, the Lake Isle of Innisfree, Berggasse 19, Richard Wright’s elementary school (or perhaps it was just his schoolchair and the school had been torn down — I can’t remember). How could anyone not be shaken up by reading Franz Kafka’s famous (and famously unsent) 1918 letter to his father now on display at the Kafka Museum? Imbued with the authenticity of Franz’s own cramped, unerringly legible handwriting? Partly, in all these journeys, I was looking for that very same authenticity, the dirt and the air Hrabal or William Faulkner had actually breathed, the unmediated sources of their perfect art. But I was also looking for, and more often finding, myth. Sometimes there were anecdotes embellished by the author, for instance, the public images enthusiastically promoted by Sigmund Freud and Nathaniel Hawthorne; other times, the rumors had been mooted by rivals, promoters, surviving family, and friends.

Over a recent weekend, I consumed Sarah Stodola’s Process: The Writing Lives of Great Authors. Stodola reconstructs the careers, habits, and influences of major writers in English of the last century, from Edith Wharton to David Foster Wallace; each section ends by summarizing the author’s daily writing routine, and anything that might have disrupted it (Wharton’s frustration over an unsatisfactorily arranged hotel room, Wallace’s lack of discipline). It’s a well-researched book that is affably written and organized, though the choice to avoid quoting or expanding on each writer’s career development seems like a missed opportunity.

Over a recent weekend, I consumed Sarah Stodola’s Process: The Writing Lives of Great Authors. Stodola reconstructs the careers, habits, and influences of major writers in English of the last century, from Edith Wharton to David Foster Wallace; each section ends by summarizing the author’s daily writing routine, and anything that might have disrupted it (Wharton’s frustration over an unsatisfactorily arranged hotel room, Wallace’s lack of discipline). It’s a well-researched book that is affably written and organized, though the choice to avoid quoting or expanding on each writer’s career development seems like a missed opportunity.

Though each chapter takes a writer in detail, Stodola has focused on the “horizontal and vertical,” things that avid readers might find interesting, such as the controlling “image” that guides Toni Morrison’s work or how much time Ernest Hemingway really gave over to socializing. I was reminded of peculiar trivia I had read years ago, but hadn’t fully appreciated at the time: James Joyce’s early infatuation with Henrik Ibsen, Philip Roth’s habit of writing hundreds of pages before finding the first useable syllable.

I’ll almost certainly return to Process when my own enthusiasm for revising wanes, or when I finally start The Custom of the Country, and would like to pluck some well-curated details about its author. Though I also know my interest is slight compared with the insatiable, obsessive appetite of some writers, my fascination is not just a type of highbrow celebrity cult, which tends to be less about the person’s work and more about Puritan pillorying. There is no prying into their intimate lives, either, since I’m mostly interested in things that the authors considered “fair play” — documents sold to libraries, autobiographical writing published with their permission, property that their families curate on their behalves — rather than, say, Henry James’s sexuality.

I’ll almost certainly return to Process when my own enthusiasm for revising wanes, or when I finally start The Custom of the Country, and would like to pluck some well-curated details about its author. Though I also know my interest is slight compared with the insatiable, obsessive appetite of some writers, my fascination is not just a type of highbrow celebrity cult, which tends to be less about the person’s work and more about Puritan pillorying. There is no prying into their intimate lives, either, since I’m mostly interested in things that the authors considered “fair play” — documents sold to libraries, autobiographical writing published with their permission, property that their families curate on their behalves — rather than, say, Henry James’s sexuality.

Instead, I, and thousands of others, are interested in how they chose to live with their work. I too live with their work, sometimes comfortably, sometimes miserably, the terrible beauty that their novels and poems are. Stodola offers some research, but I still wonder: How did Faulkner gain perspective on a place and people that were in such uncomfortable proximity to his Oxford house, while Joyce was able to sustain an intimacy with his city, his country, and its politics from more than 1,600- kilometers away?

2.

Megan Mayhew Bergman’s Almost Famous Women explores this theme with deft control and cool poise: how we mortals interact with genius. In these 13 stories, Bergman observes a range of influential, often-mythic, often-thwarted women: a jazz singer, bit actresses, artists. The collection’s stories examine how both their fame and femininity exerts a powerful attraction on the hangers-on, attendants, and survivors that orbit them. The “almost famous” are alternately callous, benevolent, brilliant, self-effacing, self-serving, merciless, and wounded. That word, “almost,” is singly devastating, salvific, and penetrating: their failures haunt them but haven’t doomed them.

Megan Mayhew Bergman’s Almost Famous Women explores this theme with deft control and cool poise: how we mortals interact with genius. In these 13 stories, Bergman observes a range of influential, often-mythic, often-thwarted women: a jazz singer, bit actresses, artists. The collection’s stories examine how both their fame and femininity exerts a powerful attraction on the hangers-on, attendants, and survivors that orbit them. The “almost famous” are alternately callous, benevolent, brilliant, self-effacing, self-serving, merciless, and wounded. That word, “almost,” is singly devastating, salvific, and penetrating: their failures haunt them but haven’t doomed them.

“The Autobiography of Allegra Byron” envisions the too-short life of Lord Byron’s tragically neglected daughter by Claire Clairmont. Sent to the Convento di San Giovanni before she had turned four, Allegra is a confused, frustrated child patiently nurtured by one novice nun. In one indelible scene, the abbess begins to praise the theological education of her wards to Percy Bysshe Shelley, a surprise visitor. Shelley, the formidable Romantic poet and polemicist who was expelled from Oxford in 1811 after he published The Necessity of Atheism, has turned up at the Convento to visit his niece, but is appalled to discover that the child of a Romantic arch-firebrand has to recite church creed.

Can you recite the Apostles’ Creed for your friend? the abbess said, a note of pride in her voice, as if she was eager for Shelley to report Allegra’s progress to her father.

I believe in God, the Father almighty. Allegra looked up at Shelley’s eyes, perhaps sensing his horror. Her voice fell flat.

That won’t be necessary, Shelley said, holding up one hand in protest. I’m quite confident in Allegra’s recitation.

After the girl is taken away for her evening prayers, he says to the narrator, the younger nun,

She appears greatly tamed, Shelley said to me as the abbess and Allegra disappeared down the hall, though not for the better.

A story that balances mischief and bleakness, “Romaine Returns” is about a servant named Mario, who manipulates the household of the early-20th-century artist Romaine Brooks. Brooks’s decadent youth has been ravaged by post-traumatic stress disorder, and she has become a reclusive shut-in and virtually given up art. When her friend-dealer contacts her, Mario is surprised that she had ever had friends. He wonders, “It’s hard for Mario to imagine Romaine deep in anyone’s heart. He stares at the lavender card stock with disbelief and jealousy. He wants words this intense, this loving, coming in a letter with his name on it. But he’s never been in love.”

In “Saving Butterfly McQueen,” a medical student remembers a semester she spent as a confused young religious proselytizer. In Augusta, Ga., her vanity and ambition leads her to the doorstep of McQueen. The well-known African-American actress has publicly disowned her celebrated career as a racially stereotyped movie actress and any belief in God. In Bergman’s imagined Augusta neighborhood in 1994, McQueen is glimpsed in a pitch-perfect scene: her most famous role, as Prissy in Gone With the Wind, is profoundly embarrassing in post-Civil-Rights America — the cringe-worthy “I don’t know nothing bout birthing no babies,” the staircase scene in which Scarlett O’Hara shoves her down. McQueen attempts to reclaim part of that dignity. She renounces her faith. She donates her body to science. She proudly reminds a reporter that she wouldn’t allow Vivien Leigh to slap her.

The narrator, the proselytizer, has the grace and wisdom not to explicitly point out her hypocrisy or other failings. Marco’s soul-destroying jealousy is also tautly drawn. As in many of Bergman’s stories, the writing shines through understatement, the well-placed detail, the disciplined accumulation of theme and style. That few of the sentences or passages pull at your cuff to highlight them and paste them on a Goodreads page is a testament to Bergman’s craft. Each sentence is deeply rooted in story and voice and is more effective for not having too-precious prose.

Another strength is the way that she manages to balance romanticizing her subjects with providing characters with depth and mystery. I think about my trips to see subjects when I read Bergman, because she has accomplished the hope of every literary pilgrim: reaching for a greater depth of understanding without grasping, seeing without gazing.

3.

None of this cult-worship started with my generation. Remember that Aristotle tells a fanboy story about Heraclitus: a group of foreigners decide to go out of their way on a journey to visit the famous Greek philosopher. When they arrive at his house, “they saw him warming himself at his stove.”

Surprised, they stood there in consternation — above all because he encouraged them, the astounded ones, and called for them to come in, with the words, “For here too the gods are present.”

Martin Heidegger, in his “Letter on Humanism,” claimed that the anecdote illustrates the banal, everyday dwelling of genius, or godliness. He suggests that the unfamiliar thing (god or genius) happens here among all these familiar things. They expect intellectual charisma — incendiary, paradigm-shattering, irascible — or at least a man baking bread, but find an old man in a quaint house, the most ordinary of places, where the great Heraclitus is heating his bare feet.

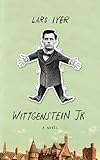

Another recent novel has also shone some insight on impressionable youth, the cult of genius, and the problem of familiarity and estrangement. Lars Iyer’s novel Wittgenstein Jr is set at a British university, among a group of graduate students enrolled in a seminar by a man who might either commit suicide or write a great philosophical work in the style of Being and Time or Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. The students half-mockingly name him after the great German philosopher. Iyer mirrors some of Jr’s behavior on the actual Wittgenstein’s own insane antics, including beating a sick child unconscious in the 1930s Austria, as catalogued in Wittgenstein’s Poker.

Another recent novel has also shone some insight on impressionable youth, the cult of genius, and the problem of familiarity and estrangement. Lars Iyer’s novel Wittgenstein Jr is set at a British university, among a group of graduate students enrolled in a seminar by a man who might either commit suicide or write a great philosophical work in the style of Being and Time or Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. The students half-mockingly name him after the great German philosopher. Iyer mirrors some of Jr’s behavior on the actual Wittgenstein’s own insane antics, including beating a sick child unconscious in the 1930s Austria, as catalogued in Wittgenstein’s Poker.

Aside from picking off biographical details, the novel itself seems to draw inspiration from the arc of Wittgenstein’s career. The first half is dense with the study of logic and propositions, before the second half gives way to a looser, direct, yet more conventional and approachable style. In the second half, Iyer almost completely discards the preoccupation with philosophical puzzle-solving altogether. The last hundred pages could be described as a kind of campus love story.

The flinty personalities. The abrupt changes in style and approach. The disembodied philosophical chatter. It’s a triumph that Iyer pulls off this high-wire act so brilliantly. It’s irreverent, smart, and off-kilter. One of my favorite passages describes the professor’s arrival at the university:

He’s trying to see Cambridge, Wittgenstein says. He’s done nothing else since he arrived. But all he sees is rubble.

The famous Wren Library!, he says, and laughs. The famous Magdalene Bridge! Rubble, he says, all rubble!

We look around us—immense courts, magnificent lawns, immemorial trees, towers, buttresses and castellated walls, heavy wooden gates barred with iron, tradition incarnate, continuity in stone, the greatest university in the world: all rubble? What does Wittgenstein see that we do not?

The bitterly wry tone comes to inform how his students respond to Wittgenstein’s baffling lectures. Wittgenstein’s classes dwindle in size, and his remaining students are mostly half-hearted in their attempts to emulate his philosophical dedication. Instead they’re preoccupied by his general oddness, his sexuality, his comments that seem to indicate that he plans to kill himself, and his tendency to use intellectual palaver to disrupt Cambridge’s bourgeois conventionality:

A don, walking his dog, greets Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein nods back.

The dog is a disgusting creature, Wittgenstein says when the don is out of earshot. Bred for dependency. Bred for slobbering. We think our dogs love us because we have a debased idea of love, he says. We think our dogs are loyal to us because we have a corrupted sense of loyalty.

People object to pit bulls and Rottweilers, but pit bulls and Rottweilers are his favourite dogs, Wittgenstein says. They don’t hide what they are.

People love Labradors, of course. But the Labrador is the most disgusting of dogs, he says, because of its apparent gentleness.

Some undergraduates might be able to resist such deliberately provocative cant. But a handful of students can’t resist those kinds of observations, the type that seem to reanimate the banal surface of things, spoken by a deeply knowledgeable university professor. They form a quasi-cult around him and can’t resist his unusual charisma. To this day, I can’t resist charismatic thought, however flawed or incomplete the idea might be, and I’m not likely to learn how to anytime soon.

For that matter, I can’t resist putting together a “lit-itinerary” for a trip I plan to take to East Asia later this year. Did you know there is a recreated statue of Apollo on display at the Yukio Mishima Museum? How well did Kenzaburō Ōe’s mother keep her lawn? Perhaps, the Museum has a recorded testimonial from one of his neighbors, complaining how he was really just a lazy, drunk slob — I can hope. And I ask myself, in what Kyoto bar might a fellow literary pilgrim relate to me the praiseworthy sexual longevity of one of Japan’s great dilettante artists?