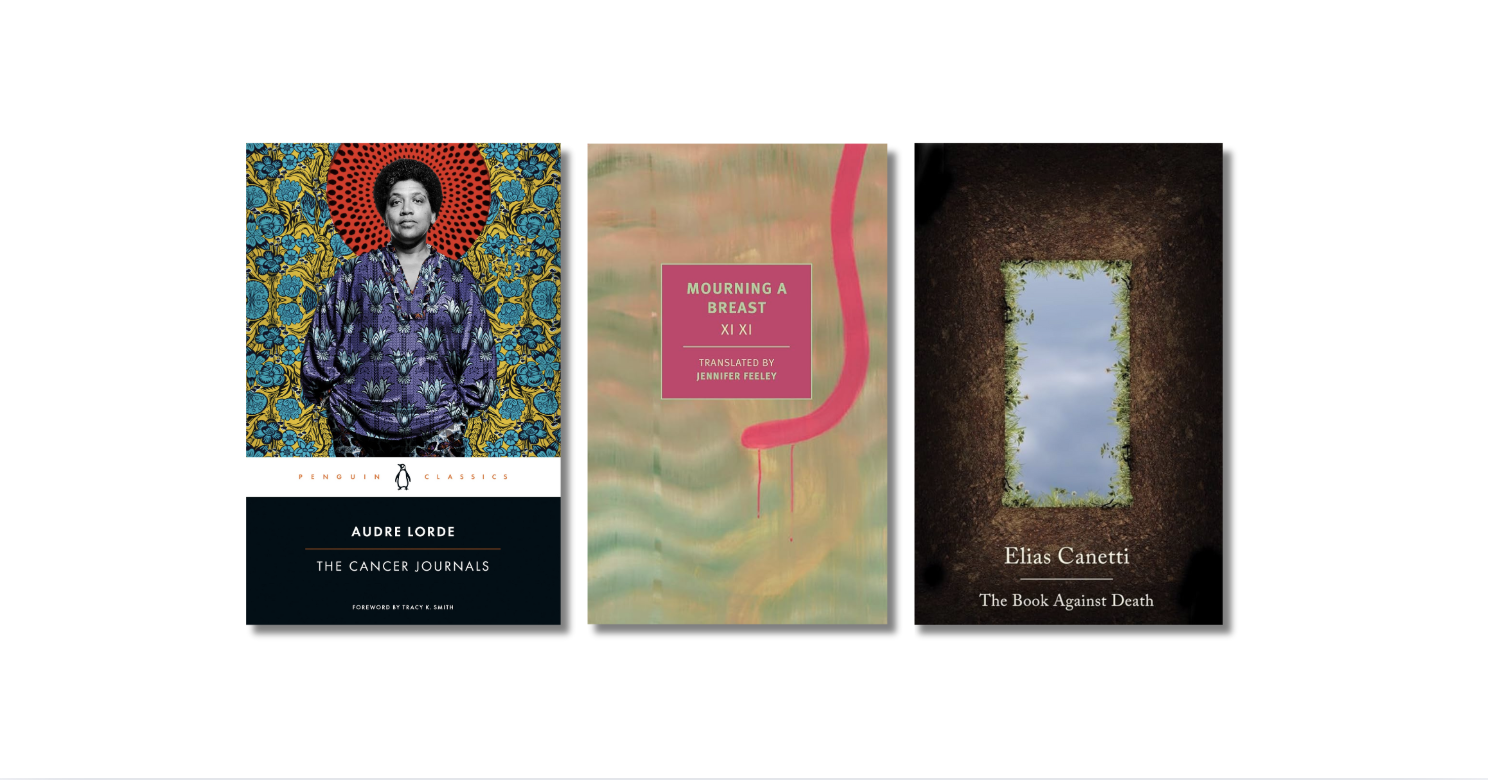

Last winter I found myself lost in a draft of a novel, unable to keep track of the events in my book and getting hung up on unimportant logistical details. I felt kind of stupid because my story was simple, one that only took place over a few months in 1996. I had a list of scenes and an outline of what I had written but the only way I could really get my bearings was to Google old lunar calendars. Finally, I took a big piece of paper from my son’s easel and drew a three-month calendar that I could look at as I worked. In the calendar squares I wrote the events of the story, like a diary. After I did that, it was much easier to write. It was as if my brain could finally relax once the events of the story were organized in a familiar way.

Shortly after I drew this calendar, I read an interview with Michelle Huneven on this site and smiled in recognition when she explained that “the difference between short stories and novels is, with a novel, sooner or later you’re on the floor with a pad of paper making timelines and calendars and family trees.”

Then, last fall, I was reading The Millions interview with Emily St. John Mandel and was fascinated by the spreadsheet she created to organize her novel Station Eleven.

I got curious about the other visual aids that novelists create to manage their books, so I asked around and gathered a variety of notebook pages, diagrams, and timelines. In my search for material, I was often stymied by two factors: 1) writers had thrown out notes and materials related to finished novels and 2) writers were nervous about sharing their notes, especially for works-in-progress.

I can certainly understand this vulnerability, and in fact I still feel a little silly about the calendar I’ve shared above. I doubt I would feel so foolish if I were working on a biography or reporting a complicated story from a variety of sources. But there’s something about making a diagram or calendar for an imagined world that feels over-the-top or maybe borderline delusional. So, I thank the writers below for sharing (and saving!) their peculiar and illuminating designs. And if you’re in the midst of a novel now, and stuck, maybe the answer is not to keep typing but to get a blank piece of paper and start drawing.

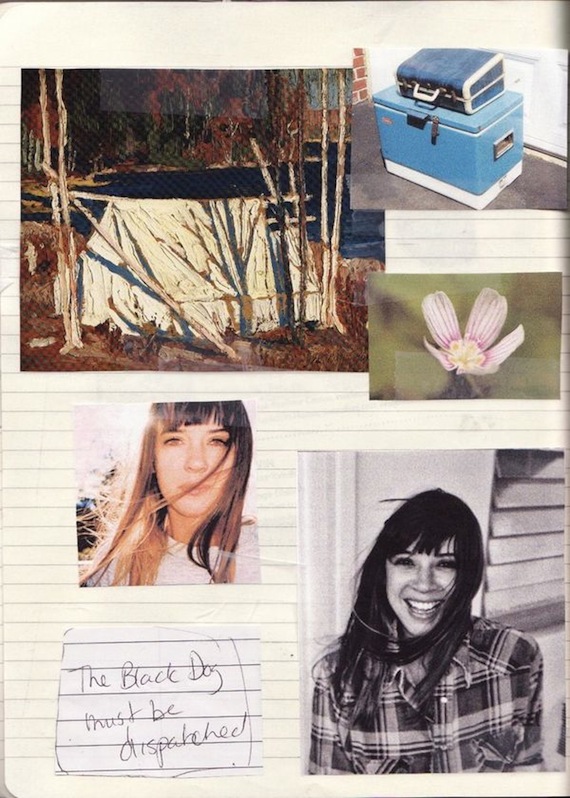

Claire Cameron, notebook pages for The Bear

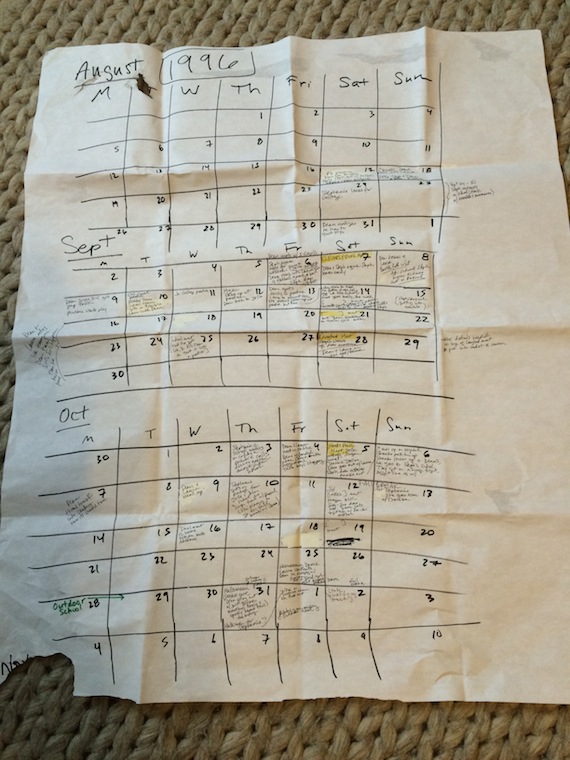

I am always underlining, clipping and making notes. Sometimes I decide that it’s time to put some of these little bits of paper into a notebook. I like to think that I’m working on my visual side, but lately I’ve realized that I’m actually thinking. When my hands are busy, my mind is free to run.

These are a couple pages that I made around the time I was writing my recent novel, The Bear. It’s a survival story of two young kids who are lost in the wilderness after their parents are killed by a black bear.

This page gave me a feel for the mix of vulnerability and resilience of the kids in The Bear. I read about Kotjebi or ‘fluttering swallows’ — street kids in North Korea. Apparently they are often seen with a tube of toothpaste in hand as they believe it will help with the constant indigestion that comes from garbage-based diets. It’s crushing to think about, but it’s also the opposite of helpless. The kids are forming their own culture to help them survive. The stark, blocked composition in the Herzog photo spoke to me of a certain toughness. And that women. No one is going to mess with her, right?

The Bear ends with a short epilogue where the grown kids revisit the site of the bear attack. I knew the exact note that I wanted to hit — I could hear it — but I couldn’t find it in my keyboard. I made this page while I was thrashing through that part of the edit. I thought, what do I know? And I stuck that all on a page.

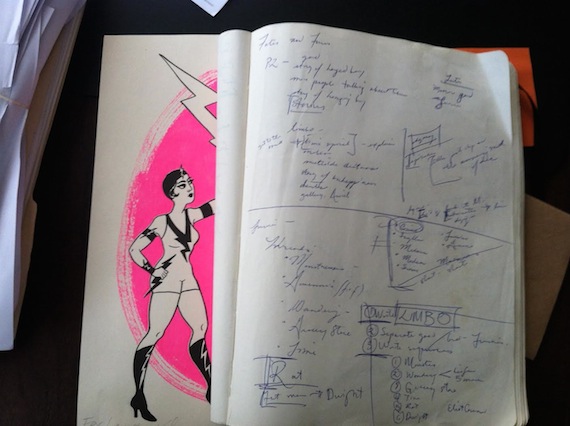

Lauren Groff, notebook pages for Fates and Furies (forthcoming from Riverhead, September 2015.)

This is a page of my notebook that I used in writing my next novel, Fates and Furies. I’ve thrown out the enormous eight foot square wall-maps of incident and character that I relied on during the first three years of writing this novel; this page from my notebook is from just after I discovered I hadn’t been writing the two slender novels I thought I’d been writing, but rather one (much fatter) novel. I love revising, but am easily overwhelmed, and I have to make lists and only concentrate on one change at a time to get through it all. Though this page is incomprehensible to me now (more god? Fat man — & Dwight?), at the time it was my roadmap for the things I needed to do, from most urgent to least. The drawing under the notebook was given to me by my next door neighbor and friend, the kick-ass cartoonist Leela Corman, and it powered me through finishing the manuscript.

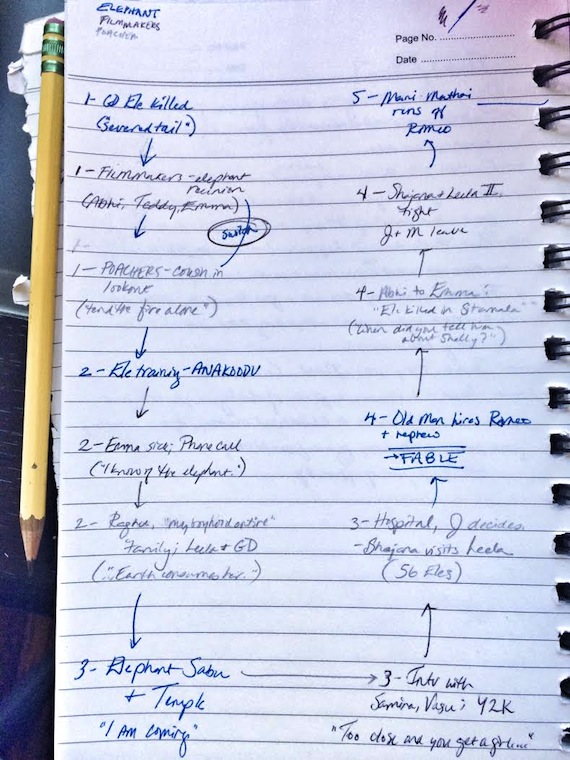

Tania James, notebook page for The Tusk That Did the Damage

I wrote a novel, The Tusk That Did the Damage, that involves three different perspectives, that of an elephant, a filmmaker, and a poacher’s brother. Even with these differing perspectives, I wanted to keep the story flowing forward, to have the tail end of one section feed into the next. Hence my predilection for arrows.

Scott Cheshire, notes from High as the Horses’ Bridles

I found this page, one of about five pages I used to occasionally and desperately display on my desk because they apparently helped me keep things “in order.” Scrawled with phrases like “cell-phone logic,” “truth!?,” and “BOIL X2,” I have no idea what they mean anymore. They look embarrassingly like those pieces of paper you see on cop shows, pinned to walls behind the desk of a brainy detective working on a tough case. My favorite phrase from this page: “This is the thing — Joe.” Joe is underlined, and circled. I have no idea who he is.

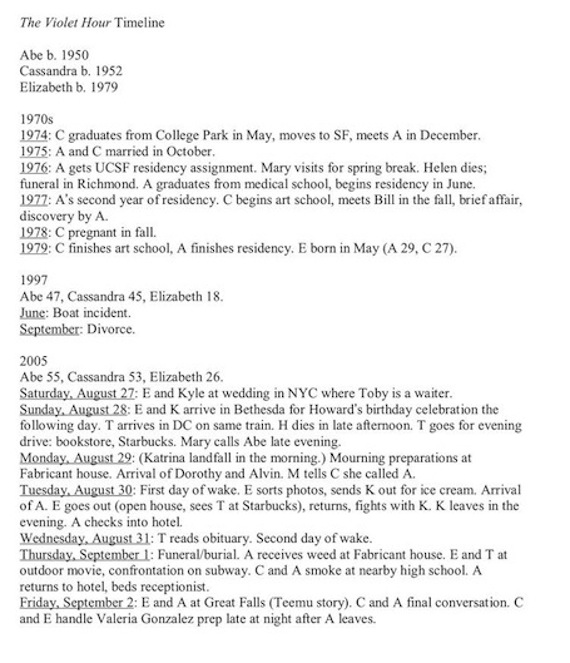

Katherine Hill, timeline for The Violet Hour

I began this timeline to keep track of all the narratives I’d started when I was drafting The Violet Hour. The early versions were really messy and full of question marks and speculations. But by the time I was making my final revisions, the timeline had grown shorter and tighter, and I was using it as a kind of retrospective blueprint: a file I could reference to make sure everything in the world of the novel was in line. It’s a document of the novel’s events — or most of them — but it’s also, in a very real way, a document of the novel’s process. By the time it was done, I knew the novel was basically done, too.

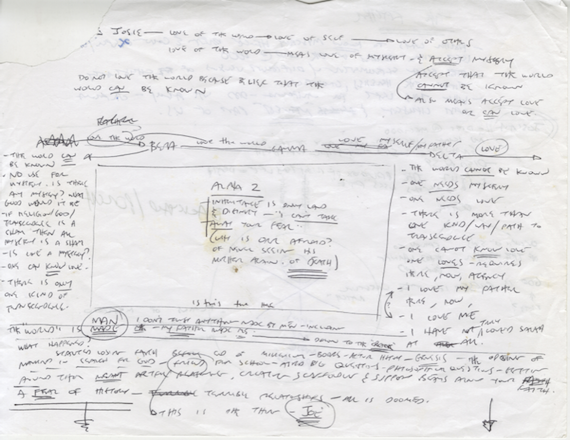

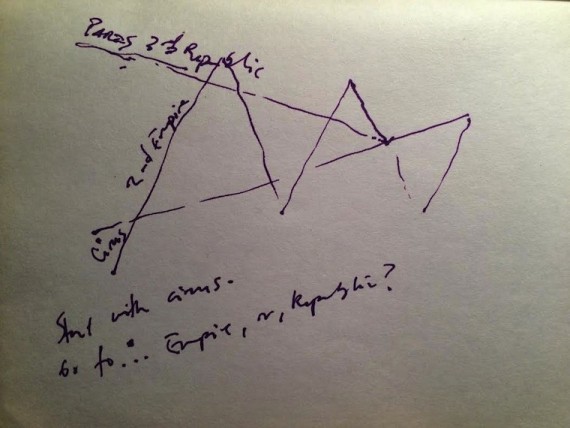

Alexander Chee, drawing for The Queen of the Night (forthcoming from Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, Feb. 2016)

This is a drawing I made in the back of my copy of The Kill by Emile Zola, which I was reading for research at the time. One of the hardest things for me to figure out with The Queen of the Night was how to structure the story. The novel is about a woman searching her memories of her past, identities she’s adopted and discarded in order to survive a world that wasn’t made for her to survive in. My narrator is the kind of woman I would glimpse in little glances to the side in novels like The Kill, and I wanted to make a novel that put her at the center. But it is very tricky to write a novel about someone who lies to themselves and others in order to live — telling the truth even to herself is dangerous.

When I did this, I had written several drafts, writing and then discarding sections until I realized the discard file — where I saved everything — was the novel. It was a novel composed out of rejected selves. This drawing then was one attempt to get the structure right. It’s not what ultimately happened for the structure, it’s a middle version I moved on from, but it helped me get there.

I took a learning styles test once that told me I was a visual mathematician, and while I doubted it at the time, I think that it is true. I first did it to diagram a novel whose structure I was trying to understand while working on my first novel. I do it on chalkboards with my students now, to explain the way the force of the narrative moves the reader’s attention. Looking at this now, I might have to get this made into a t-shirt to wear while on tour.

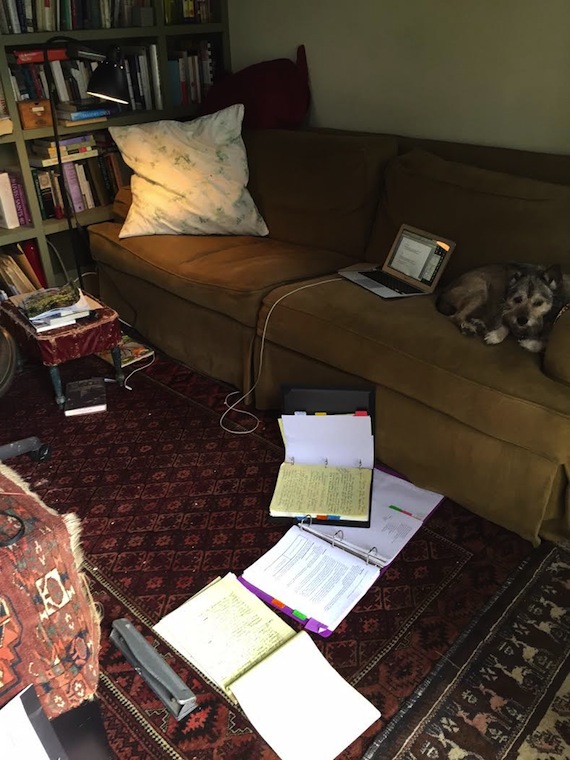

Michelle Huneven, binder notes for a work-in-progress

I am writing a novel about a church’s search for a new minister. I am following an actual process as determined by the denomination, which means I have a series of events in a set order that I have to somehow make dramatically interesting. I have all of these pamphlets and brochures and guidelines outlining the process; I have timelines, I have interviews with people who’ve conducted searches and those who’ve been hired (or not). And then, I have seven characters on the search committee who all have stuff going on in their lives…

For a long time I had two or three manila folders of notes and any number of “notes for novel” files on my computer. A good portion of my writing day was spent trolling through these files for the nugget I needed, which was fine for a while because it familiarized me with all the stray bits I’d accumulated.

Then, I started writing the book itself by hand on legal pads. And not on the same legal pad. Which meant that, when I wanted to write, I had to go through various legal pads to find where I wanted to work. That, too, was fine for a while, because I was constantly reviewing what I’d done. But at a certain point the accumulated disorder had me whimpering.

Down to the floor I went. I had inherited my mothers three-hole punch (she was an elementary school teacher), and I had an empty three-ring binder sitting around, so I printed out all the notes on my computer, and put them in the binder with all my other notes and pertinent papers. Soon, it came clear that having research and writing in one binder was inefficient — too much paging back in forth. So it was off to Office Depot, where I bought more binders and file dividers, and spent some very happy hours on the floor punching holes and organizing. (Since then, I also created separate binders for short stories and journalism…and, yes, recipes.) The floor of my office, as you can see from the picture, is my largest flat surface, so I’m down there when researching, and also when punching holes in new material. I can also work from both binders while writing…which proves that, at certain points, the floor is more useful than the computer screen.