1.

I read a lot of headlines about the Sony data hack before I mustered the interest to read anything else about it. There are so many things to click, and the headlines seemed to concern only empyrean Hollywood types, and I am on maternity leave and partially brain-dead. Someone was racist, a woman made less money than a man, something about Angelina Jolie. But eventually the headlines became so relentless that I finally clicked, like an old bloodhound heaving her bulk from the porch and loping off in the direction of a rumpus. I began with one exchange of emails between Sony bigwigs Scott Rudin and Amy Pascal and was immediately so enthralled that I went hunting for others that had been published on the various news sites.

Last year I was sent a copy of the highly experimental Nanni Balestrini work Tristano, the result of a machine randomly shuffling 10 different chapters of an already experimental 1966 novel to create eerie nothings like this:

Last year I was sent a copy of the highly experimental Nanni Balestrini work Tristano, the result of a machine randomly shuffling 10 different chapters of an already experimental 1966 novel to create eerie nothings like this:

A long thin rivulet of water slowly advances on the asphalt. She moves slowly under his body. The woman answered no certainly not.

I found Balestrini’s novel alien and repugnant because I am wedded to more traditional narratives; for me all intention and meaning had been stripped from its words by virtue of its reshuffling. But Pascal and Rudin’s emails, which are basically incomprehensible to anyone outside of their industry, are somehow more compelling by virtue of their incomprehensibility, Amy Pascal’s sibylline utterances full of a surprising sort of illiterate pathos and mystery:

I would do this for you

You should do this

II [sic]

Miranda July capitalized on the seductive nature of other people’s mail in the summer of 2013 with “We Think Alone,” an art project whereby people could sign up to receive forwarded emails from celebrities’ inboxes. This was an inspired choice; snooping around people’s emails hits pleasure centers arguably more primal than those tapped by schlepping to a museum, paying $25, and getting a headache after 30 minutes looking at a pile of cat food cans welded together. And while for some people it’s the snooping itself that makes other people’s mail interesting, readers with qualms about privacy could feel secure in knowing that the celebrities themselves had provided access. (N.B: while personal correspondence should be off-limits unless the recipients have consented or are dead, I feel okay about quoting from the Sony leak, and the Wikileaks emails below, because they are ostensibly corporate records, and not personal ones.)

Some commentators observed that Miranda July’s curated emails did not reveal anything particularly titillating about these celebrities (among them Kirsten Dunst and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar), but I found the voice of their communiques as compelling as the things disclosed therein. Note the lilting, seemingly non-native English of Kirsten Dunst’s email here:

I also have some great experiences from yesterday as I was in a photo shoot for Bulgari, and there were so many elements and people. I have very strong Ideas to talk about.

I’ll do the second assignment tomorrow, I have a night flight to Boston and it’s hard for me to get in a comfortable place in sleep to dream.

If Kirsten Dunst’s email selections revealed that there is a level of fame at which you don’t really need to worry about what you sound like, to the extent that you are willing to forward your strange musings to thousands of strangers, Pascal and Rubin’s emails indicated that the more money and prestige are attached to your job, the more your professional correspondence is likely to be composed and punctuated like a comment on a Huffington Post article. But more importantly, they show a mode of communicating that has been molded by the melodramatic conventions of the very industry that produced it, plaintive lines like “Don’t pretend all thoes things didn’t happen cuz it makes me feel like I’m going crazy” or “Why are u punishing me”; admonitions like “You’re involving yourself in this massive ad pointless drama that is beneath you”; or the more ominous “You’re about to cross a line that won’t get uncrossed after you do it.”

In 2012, Wikileaks published millions of emails harvested from Stratfor, a global intelligence research firm in Texas. Wikileaks and the news media were interested in these emails for their geopolitical implications, but they also represent a veritable cornucopia of narrative pleasures, all the more delectable because they are strange and secret and real. They likewise reflect a very particular professional sensibility, sometimes self-conscious, often comic, and full of bravado. Even a fractional survey of the emails’ subject lines is evocative: “Fucking Tajikistan;” “Fucking Europe;” “Fucking Russian Defense Guys;” “Fucking Abottabad;” “fucking Mubarak;” “fucking guatemalans;” “fucking Belgium;” “fucking kangaroos;” “fucking hipsters;” “what a fucking shit show;” “Get ready to be hit in the fucking face with a fist full of friendship;” or the succinct command, “pay the fucking utility bill.”

There is no way that a person could read all of them, and random clicking might yield all sorts of tantalizing fragments, à la Balestrini by way of Graham Greene:

I mean look, I never said that the fact these camels/horses came from tourists

meant it wasn’t organized, right. I was just saying that the horses/camels

don’t mean anything in of themselves. There are horses/camels near the

city and in considerable numbers.

These are corporate records, but they are also full of human currents, intimations of complex, even tender relationships:

Reading this, I get the sense that you, in some sense, fear and crave

change at the same time. You find beauty in the concept of change, but to

a limit. You fall back to the comforts of familiarity, the languid

porches.

2.

The joy of reading other people’s mail is a well-known, well-documented phenomenon. Anyone who has spent time in an archive has found themselves wandering through the hedge maze of correspondence, which can lead either to fruitful new projects or simply leave the reader floundering in some voyeur’s backwater, pointlessly obsessing over the sheer novelty of the way that people communicate with one another. We have epistolary novels, of course — themselves a product of human interest in other people’s mail and the narrative possibilities thereof. No sooner had the novel been invented than it had been given the epistolary treatment, in Samuel Richardson’s Pamela and Clarissa.

The joy of reading other people’s mail is a well-known, well-documented phenomenon. Anyone who has spent time in an archive has found themselves wandering through the hedge maze of correspondence, which can lead either to fruitful new projects or simply leave the reader floundering in some voyeur’s backwater, pointlessly obsessing over the sheer novelty of the way that people communicate with one another. We have epistolary novels, of course — themselves a product of human interest in other people’s mail and the narrative possibilities thereof. No sooner had the novel been invented than it had been given the epistolary treatment, in Samuel Richardson’s Pamela and Clarissa.

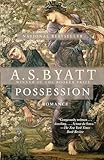

Contemporary novels use correspondence not only to drive a story, but to attempt the herculean work of capturing the spirit of an age — past, present, or future. Some of these are convincing — better, even, than reality — like A.S. Byatt’s divine Possession, built around an amazing fabricated correspondence that works to make the novel simultaneously a mystery, love story, and postmodern work of criticism. Gary Shteyngart’s Super Sad True Love Story constructs a textual future English patois, told through the “Globalteen” messaging accounts of two young women. But these and other wonderful novels that have successfully used the epistolary format cannot scratch the very specific itch of the leaked email, the archived letter. As Shteyngart’s sad sack anti-hero Lenny Abramov writes in his diary, describing his new electronic device: “I’m learning to worship my new äppärät’s screen…the fact that it knows every last stinking detail about the world, whereas my books only know the minds of their authors.” There is a fundamental inauthenticity to the epistolary novel; we cannot forget that it sprang from the mind of its author.

Contemporary novels use correspondence not only to drive a story, but to attempt the herculean work of capturing the spirit of an age — past, present, or future. Some of these are convincing — better, even, than reality — like A.S. Byatt’s divine Possession, built around an amazing fabricated correspondence that works to make the novel simultaneously a mystery, love story, and postmodern work of criticism. Gary Shteyngart’s Super Sad True Love Story constructs a textual future English patois, told through the “Globalteen” messaging accounts of two young women. But these and other wonderful novels that have successfully used the epistolary format cannot scratch the very specific itch of the leaked email, the archived letter. As Shteyngart’s sad sack anti-hero Lenny Abramov writes in his diary, describing his new electronic device: “I’m learning to worship my new äppärät’s screen…the fact that it knows every last stinking detail about the world, whereas my books only know the minds of their authors.” There is a fundamental inauthenticity to the epistolary novel; we cannot forget that it sprang from the mind of its author.

The ludicrous Tumblr, “Texts from Bennett”, which purports to be the SMS record of a Midwestern white boy with delusions of hood status, seems cognizant of the disappointment that undergirds epistolary works of art, guaranteeing in its header that it is “100% Real.” It’s not real, though, and its offerings are ultimately unconvincing, a collection of zany, “urban”-inflected bon mots:

The ludicrous Tumblr, “Texts from Bennett”, which purports to be the SMS record of a Midwestern white boy with delusions of hood status, seems cognizant of the disappointment that undergirds epistolary works of art, guaranteeing in its header that it is “100% Real.” It’s not real, though, and its offerings are ultimately unconvincing, a collection of zany, “urban”-inflected bon mots:

like I said I luv anamels alot 2. i used to rescue rockwilders im one of da highest paid members of PITA.

If “Texts from Bennett” is obviously fake, it is grasping at the heart of leaked mail’s allure. The Tumblr was so popular that it was in fact turned into a novel, one with a surprising number of positive reader reviews, many of which expressed sentiments along these lines: “We all know an incredibly white person who attempts to act as ghetto as possible, but Mac Lethal knows whats up with Texts From Bennett.” (Reading Amazon reader reviews, like Internet comments, comes close to scratching the epistolary itch. Reading comments can be irresistible, not for the opportunity to wallow in outrage about the ignorance or malevolence of your fellow clicking public, or not only that, at any rate — it’s that intimate glimpse at the way people communicate, the things that they say and the ways that they say them. There is nothing like a YouTube comment for revealing our humanity in all its forms.)

Most correspondence we have the opportunity to read is of the highest caliber, composed by great minds and published (perhaps even written, at some level) for the public’s edification. So we have the letters of Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, or Rilke, or Patrick Leigh Fermor and Deborah Devonshire née Mitford. These are gorgeous pieces of writing, but they assume an unrealness by virtue of the genius of their authors; they are artifacts of an age and class for which correspondence was understood as an art form. I remember the surprise, the electric thrill, of reading, at of one of my many past part-time archival jobs, a letter written by a regular enlisted man in World War I. Far from the texts of my college Modernism curriculum — the majesty of the war poets, the self-conscious zip of BLAST or the raffish style of the Wipers Times — the letter was rife with misspellings and homey sentiment, the product of a semi-literate young man sending a short and melancholy message home to his mother. I had never thought about what a normal person might sound like during that era. There can be great style and meaning in unstylishness, “Texts from Bennett” notwithstanding. (The Telegraph published a batch of WWI letters written in a similar vein: “I am very sorry for what I done when I was at home and will pay you back when I get some more pay.”)

We are awash in narrative these days. We are in a golden age of television, where highly polished narratives are whipped up by streaming video companies, tailored to our mined preferences, and basically guaranteed to be addictive. Even our news gets a narrative now: something happens — like the Sony leaks, for example — and we have not only the text, but the meta-text, the commentary on ethics and implications. We have lovingly and expensively produced radio plays based on real-life murder cases, and rounds and rounds of narrative about whether they are bad or good and what they say about our culture. Forget the forest/trees taxonomy; we are so spoiled for narrative that we have multiple forest visualizations — time, space, temperature.

Readers and writers, I think, are particularly susceptible to the narrative delights of real correspondence, which will always exceed the limits of any one novel’s philosophy. A building of Paris’ Palais de Chaillot is inscribed with a verse of Paul Valéry:

It depends on those who pass

Whether I am a tomb or treasure

Whether I speak or am silent

The choice is yours alone.

Friend, do not enter without desire.

Archives are a public good, but they are predicated on this desire. In one sense, my interest in the recent leaked emails is narrative hunger taken to its most pathological reach. Rather than lament the implications of the Sony emails (that insanely rich and powerful white people are still a bunch of crummy racists; that people spend millions of dollars to make shitty movies while the world burns) or the grim findings of Wikileaks (that there is a revolving door between the government, business, and security sectors), I treat these documents as another avenue for narrative desire. But there’s nothing like the magic of an authentic human document. We are surfeited on the “what” of the narrative. Leaked emails give us that rare and precious thing, the “how.”

Image Credit: Flickr/Jason Rogers