It’s not news drawing attention to the fact that books released in different markets almost always have different covers. But what do we make of three different editions of an illustrated fiction, two of which have been translated to English from Japanese, with covers and interiors that could not be any more different from one another? Such is the case with the latest Haruki Murakami book, The Strange Library. What’s that? You thought Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage was the most recently translated Murakami novel? You are correct, and incorrect. Without getting involved with trying to delineate the differences between a novel, a novella, and a short story, it just doesn’t seem right calling The Strange Library a novel. The U.S. edition is a 96-page paperback with elaborate flaps that open vertically and the 88-page U.K. edition is small hardcover embracing the library conceit with a check-out card holder on the cover — both versions are heavily illustrated and use the same Ted Goossen translation, with American English spelling and punctuation, and the text probably only takes up about half of the pages in both editions. The Japanese edition is also illustrated and was released in 2008 in the compact dust-jacketed paperback format known as bunko-bon.

Murakami’s most enduring talent is his ability to rein in his expansive imagination with sentences strung together with elegant simplicity. As is the case in most, if not all, Murakami, The Strange Library features a male protagonist unexpectedly caught out of sorts, unsure how to extricate himself from the predicament, and reliant on eccentric characters, one of whom is, of course, a beautiful young woman. In many ways, The Strange Library is familiar territory, but even by Murakami’s standards this prose is sparse, and, it turns out, secondary to the storytelling.

Murakami’s most enduring talent is his ability to rein in his expansive imagination with sentences strung together with elegant simplicity. As is the case in most, if not all, Murakami, The Strange Library features a male protagonist unexpectedly caught out of sorts, unsure how to extricate himself from the predicament, and reliant on eccentric characters, one of whom is, of course, a beautiful young woman. In many ways, The Strange Library is familiar territory, but even by Murakami’s standards this prose is sparse, and, it turns out, secondary to the storytelling.

The unnamed narrator goes to the library to return books and find more about tax collection in the Ottoman Empire. After being directed to a room in the basement, the narrator is confronted by a cranky old librarian who procures three tomes. The appreciative narrator tries to check out the books only to learn that they cannot be removed from the library. Not wanting to worry his mother by being late for dinner the narrator apologizes for any inconvenience he might have caused the crusty librarian, but the old man guilts the narrator into staying after hours, at which point he forces the narrator down a dark staircase and imprisons him, with the assistance of a sheep man. The narrator is ordered to read the three books the librarian pulled for him so that the old man can eat the narrator’s brain. When the narrator asks why, the sheep man explains, “Brains packed with knowledge are yummy, that’s why. They’re nice and creamy. And sort of grainy at the same time.” Without spoiling the ending, that’s The Strange Library.

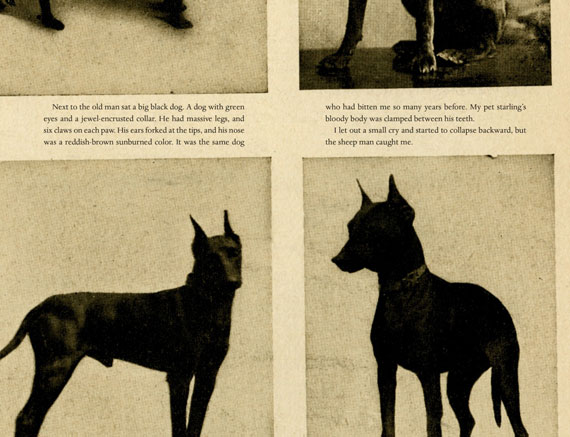

The story’s pacing is dreamlike with very little consideration of events as they happen and how they are all accepted no matter how absurd. When the narrator is told his brain will be eaten, he isn’t happy about it, but he resigns himself to the idea and gets reading about the Ottoman Empire. As captors go, the sheep man is quite likeable, especially since he fries up a mean doughnut. The enchanting woman is mute, but the narrator is able to communicate with her effortlessly. From a psychoanalytic perspective, it is not a reach to posit that we are reading the narrator’s dream. The old man could easily symbolize an estranged father figure and the repeated appearance of a green-eyed dog represents trauma. Plus, a library, like a brain, is a place full of knowledge we think we want to access and knowledge we have no idea that we want to access, or should access.

Everything that comes to pass in The Strange Library, like in so much of Murakami’s fiction, questions the differences between what is real and what is not, and whether such a distinction even matters. In 1Q84, the intersection of two different temporal realms drives the plot, and in Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki, certain occurrences take place in “reality, but a reality imbued with all the qualities of a dream.” But in both of these books the characters devote themselves to fleshing out the mysterious intricacies of these unreal realities, whereas in The Strange Library the narrator simply accepts everything that comes his way.

The illustrations, more than the words on the page, are what ignite the reader’s thoughts about what the narrator is up against. In the Japanese edition the kooky Saturday morning cartoon images are quite literal — there is the narrator crying on his bed, a ball and chain shackled around his ankle; and here is the sheep man carrying in a tray of doughnuts. There is nothing dark and foreboding about the images and they come off more like an afterthought and not integral to the text (which I cannot read).

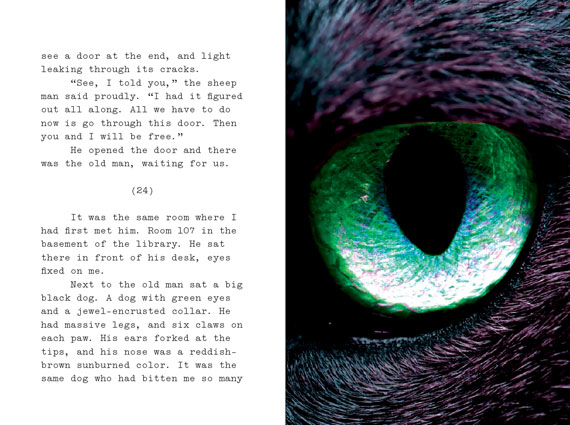

What is immediately clear upon seeing both English-language editions is just how much thought went into the design and illustrated content of these two very different books. Published by Knopf, the U.S. edition is a Chip Kidd production (top), and while Kidd’s prolific portfolio demonstrates how comfortable he is working within any and all design idioms, The Strange Library is an in-your-face zoom-in on the faded comics qualities Kidd so often employs when working on Murakami titles. Suzanne Dean, art director for the book’s U.K. publisher, Harvill Secker, takes a very different approach to The Strange Library (bottom). Open up that edition to any page and the word “vintage” will spring to mind, from the lovely marbled endpapers to the reproduced antique plates of dogs and birds.

Both designs inject a sinister quality into the goofy story, but the illustrations and design interact with the text quite differently. In the U.K. edition, the illustrations and design are about much more than ornamenting the story; the illustrations actually complete sentences and respond much more literally to the words on the page, making the relationship between the two dependent on one another. In the U.S. edition, certain of the illustrations respond directly to the narrative flow, but in a more evocative, atmospheric manner. Some of the images, judging by the colors and pulpy quality, appear to have been scanned from source material that probably qualifies as vintage, but how they are used on the page gives them a more contemporary collage dynamic a la Roy Lichtenstein and FAILE.

It is fascinating that Murakami would permit his words to be so freely interpreted, but perhaps that was his intention all along with this story. As an author who has devoted a great amount of thought to dreams and dreamlike realities, it might have struck him as fitting to let designers manifest the elusive qualities of dreams on the page. (And it is impossible not to think about what these three different editions say about the differences between publishers and readers in Japan, the U.S., and U.K., but that is a topic for another time.)

Both English-language editions are aesthetically pleasing as objects, but the designs eclipse the text like a new moon-doughnut (an actual image that fills two pages in the U.S. edition). One traditional tenet of graphic design is that it shouldn’t be noticed, so as not to interfere with the reading process. Here, it is impossible not to notice the designs, but rather than distract from the reading experience the designs force the reader to actually read, and read into, the design, giving it more thought than the narrator gives to his circumstances. The three different designs employed for this one story provide readers with three very different psyches for the narrator, reinventing the narratives in a way, the same as when you remember a dream after waking up and then think back on it later in the day and it never seems quite the same.