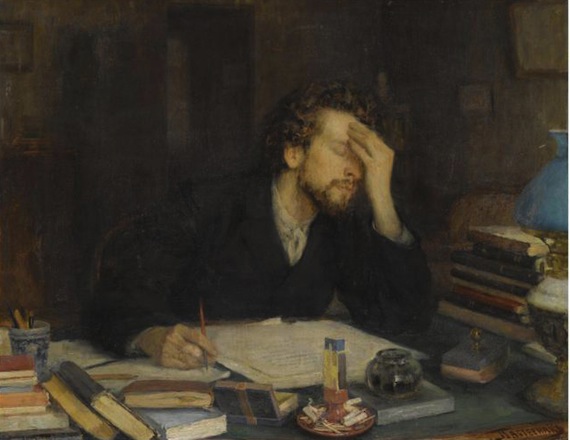

Sometimes, like most storytellers with a book or two under their belt, I’m asked if I have any advice for younger or less experienced writers. I hope the following five tips can be of some assistance.

1. Exhaust other paths to earthly renown.

Before you sit down to write, carefully ensure that a ticket to widespread adulation, or at the very least cultural relevance, is not more readily available from a more auspicious venue. Ignominiously fallen from its privileged position of yesteryear — i.e., the days when electronic media did not exist — the writing of belles lettres should no longer be considered an effective strategy for achievement of fame or fortune. Each potential alternative to this challenging and circuitous route should therefore be pursued exhaustively; a checklist can be a useful tool in the process. A few examples of superior options: Singer. Newly rich individual. Reality TV person. Naked blogger. Politician sexting victim. Politician. Tech mogul. Koch-brother style of oligarch. It is imperative, before you sit down to write, that none of these alternatives are available to you in either the short or medium term.

2. Rid writing space/home of counterproductive elements.

Children and pets, ideally, should be removed, the former in particular. Pets may remain if silent/unmoving. Some plants may also remain, if watered by others/servants. Children must be extirpated. In special contexts this may be achieved on a temporary basis, but permanent elimination is always the safer course. As a writer, you will require absolute peace and tranquility to enable a singular focus on yourself, your train of thought, indeed your every notion or desire as such. Do not live on a loud street, nor should you abide among active and loud persons. Distressed or ill persons, like children, should not be allowed to persist in your vicinity. Side note: Also, avoid passing your weeks, months, or years in a state or region ravaged by crime, war, toxins of water or air, or highly infectious disease. Nations governed by autocratic rule are permissible, but seldom preferred.

3. Provisions must be abundant.

Persistent hunger is anathema to the serious writer, much like civil strife. We recommend a fully stocked larder. We recommend, also, a well-furnished bar and wisely chosen selection of fine vintages. Poverty, whether inherited or self-made, is rarely a judicious choice for writers determined to express themselves and delicately hone their craft. Few among our thoughtful legion work well in a state of extreme destitution; there are only a handful of exceptions in recent memory, each one of whom is now, sadly, deceased. Cleave to the immortal rationalization of vaunted French scribbler Gustave Flaubert: “Be regular and orderly in your life like a bourgeois, so that you may be violent and original in your work.” Indeed we would go further still: better, far better to be a bourgeois than to live like one.

4. Be no man’s wife/no woman’s husband.

You may gather your acolytes about you, as a writer, and indeed you should do so expeditiously, for even a fledgling writer requires admiring readers as surely as a fragile ego needs to shore up strength. If you elect to follow the popular middlebrow path of academic writing, becoming for instance a poet/professor or fiction writer/professor, students can function well in this supportive acolyte role. Spouses, however — unless secured in a permanent position of eager servility — are not devoutly to be wished. Exceptions may willingly be made for an “art wife,” i.e. a domestic and professional helpmeet and facilitator of male creative output, but female writers should be advised that few, if any, “art husbands” have yet to be discovered in the annals of literary history. Thus we must counsel against the conjugal state in the majority of cases, and indeed against amorous entanglements of most kinds, which can be not only distracting but drain the serious writer of vital fluids/attention. Short-term encounters are best, in the event that human contact beyond the immediate circle of acolytes is wished.

5. Banish the critic from your mind.

In our line of endeavor, self-confidence is de rigueur. Because of its often-solitary nature, book-writing, unlike the writing of comments on websites, the posting of witticisms on social media, etc., must be pursued, at least in part, absent the constant and daily input of our fellow humans. This, in any case, has been the traditional model. In this regard, two items are worth noting: first, a writer must banish the inner critic, that critical force that lurks within your own intelligence. An overzealous, naysaying mental habit is death to the production of both prose and verse. Second, banish the outer critic handily. Yes, there will be those who argue against the value of your work; ‘twas ever thus. There will be those who gainsay your genius, at various points; those, in publishing and reviewing equally, who turn their faces from the gifts you give. These unenlightened souls cannot be allowed to enter your mental world. Remember always that, as writers, we give because we must. We give, at times, despite the knowledge that our gifts may not be needed, wanted, or enjoyed. For us — we must remind ourselves — the joy is in that selfless offering.

Image Credit: Wikipedia