The central characters of the first season of The Returned, an addictive and deeply unnerving French television drama available on Netflix, are identical twins, Camille and Léna. When we first meet Camille, she walks briskly up the road to her parents’ house in a polished town in the high Alps. Léna, meanwhile, is doing shots at the town’s rather youthful bar, the Lake Pub, named for the massive hydroelectric dam down below.

Léna drinks and drinks some more, apparently chasing a demon. Ravenous, Camille devours a sandwich. What’s to account for the intensity of their behavior? Four years earlier, at the end of a school field trip that Léna should also have attended, Camille was killed when the tour bus went over a cliff as it returned to town.

Soon, we are to realize, Camille isn’t alone among the confused and hungry dead who have just returned to walk among the living. A retired schoolteacher, Mr. Costa, has hidden his wife, who died in 1978, in the kitchen. She stuffs herself with spaghetti. Simon, who died on his wedding day, desperately searches for Adèle, his fiancée. Victor, a seven-year-old boy, lurks near a bus stop. He attaches himself to a woman with distant eyes. Indeed, the living here are as lonely as the orphan dead. And the dead feel their betrayal and exile as powerfully as do the living. “I lost my sister too,” insists Camille, when their father reminds her of Léna’s emotional wounds. Compounding the viewer’s discomfort: the script suggests that to execute the lie that allowed Léna to stay home on the day of the accident, the sisters had switched identities. Who exactly is living and who is dead?

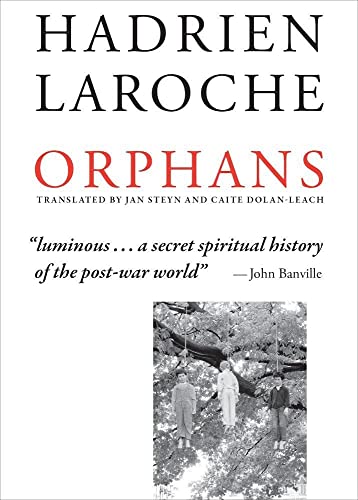

The question seems gaudy, but it isn’t just a throwaway logline for a zombie show. Not at least to the French writer Hadrien Larouche, Derrida disciple, Sebaldian investigator, playful and meticulous prober of contemporary life, whose first novel, the 2005 Orphans has just been brought out in the English translation by Jan Steyn and Caite Dolan-Leach. In this season of Patrick Modiano, Larouche is another French writer of intense and insistent vision — in one place in this novel, he gives us Osama bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri as Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, in another a man plugging his nostrils with cigarettes to keep off the stench of Serbian war dead. He is hot after the sense of personal spiritual identity in contemporary Europe, where the scars of the Second World War still bleed. He wants to know, in this meeting ground of living and dead, can anyone find comfort? “Death,” he writes, “held the living between its fingers. The dead finger kept the others prisoner.” In Orphans, the living likewise can’t let the dead be.

The narrator of Orphans, a man named Hadrien, lives in self-made exile, writing, collecting fragments of others’ lives. “I, someone who was determined to never become a collector have seen the most troubling, obscure, and subtle of collections,” he writes, in a voice that seems determined to beckon W.G. Sebald, the novelist of collected memory and material who died in a tragic accident in 2001. Hadrien’s specialty is “living apparitions,” women, mostly, “a vision of the living body from birth to death,” but, of course, who here, among the observer and the observed, is really alive? Larouche, a writer of precise and palpable sensation, wants the reader to feel the writer’s characteristic isolation, a kind of solitary death, even as he tries to immerse himself in the real lives of others. This tension frames his approach to Jean Genet in The Last Genet: A Writer in Revolt, his only other book to be published in English. “I’ve always felt well-placed in a room equipped with a bed, a table, and a stool, in someone else’s home,” observes Hadrien. “Of course, I am no longer living in my own home in any permanent fashion.”

The narrator of Orphans, a man named Hadrien, lives in self-made exile, writing, collecting fragments of others’ lives. “I, someone who was determined to never become a collector have seen the most troubling, obscure, and subtle of collections,” he writes, in a voice that seems determined to beckon W.G. Sebald, the novelist of collected memory and material who died in a tragic accident in 2001. Hadrien’s specialty is “living apparitions,” women, mostly, “a vision of the living body from birth to death,” but, of course, who here, among the observer and the observed, is really alive? Larouche, a writer of precise and palpable sensation, wants the reader to feel the writer’s characteristic isolation, a kind of solitary death, even as he tries to immerse himself in the real lives of others. This tension frames his approach to Jean Genet in The Last Genet: A Writer in Revolt, his only other book to be published in English. “I’ve always felt well-placed in a room equipped with a bed, a table, and a stool, in someone else’s home,” observes Hadrien. “Of course, I am no longer living in my own home in any permanent fashion.”

Cut loose and yet not quite trying to connect intimately with others, Hadrien finds himself in the different houses of three people, each of them an orphan of sorts. Two of the orphans he visits in the real time of the narration itself; the third is a recollection from childhood. Larouche employs various devices to move us from one place to the next, but these are transparent — he isn’t concerned with narrative. Rather Orphans is a work of observation and inquiry.

Hadrien’s second visit — we’ll return to the first momentarily — is to the home of a friend, Helianthe née Bouttetruie, who has recently married and along with her husband purchased an old farmhouse they have to renovate. The house is located in the Swiss Alps, in a village that at first seems appealing and bright. “In truth,” says Hadrien, “it slowly worked on the bodies of its inhabitants, gently annihilating them, rendering them unrecognizable, and, finally, plunging them into despair.” This doesn’t seem far from zombie television, after all.

Helianthe’s house is a mess. Her father, an architect, has drawn up an impossible plan. Her husband, Hector — every name here starts with H, as if to reinforce the author’s own sense of exile — keeps getting injured. Worse still, she suffers from a degenerative disease, an orphan disease, according to Larouche for the way its pathology isn’t connected to any other syndrome. “One day, out of the blue, the orphan disease takes shelter under a man’s or woman’s roof, and suddenly, his or her body harbors a new creature,” he says. Helianthe is short of breath, often off balance, and prone to falling down. Her left leg is three and half centimeters shorter than the right.

In spite of the disease, Helianthe wants a child. The not yet born, Larouche would say, perhaps like the dead, have a handle on the living. But what of this prospective child? Helianthe’s doctor warns her that pregnancy and birth will kill her or the baby or both. She desires an orphan.

Larouche is a post-modern writer of considerable feeling; Helianthe, essentially a subject of exploration, stands up — crookedly, for sure — for her sense of humanity. He’s best in this space, close up to the living — here where contemporary people struggle, sometimes with the dead, for identity. At times, this puts him in conversation with Zadie Smith and Elena Ferrante, two quite different European writers. Helianthe, for example, speaks at least 14 languages and regional dialects. “Arriving in a foreign country meant at once a new life and a new language,” says Hadrien, of Helianthe’s global exile. “She experienced the joy of feeling foreign to herself.”

After Hector’s latest accident, Hadrien, walking in the mountains, sees an old man that must be his cousin, Henry né Berg. This jars his memory. As a child, Hadrien had once visited Henry’s family. Henry’s father, a sadistic banker, forced Henry to use the servant’s entrance to the house. The exiled boy rejects his father’s world until at some point the desire for his own power consumes him. Now, “becoming a man exactly like his father,” he embodies the old man, who lives on inside him. In this story, the least interesting of the three for Hadrien’s lack of personal connection, Larouche echoes the tone of Portuguese writer Gonçalo M. Tavares, whose novels often explore themes of father-son domination and revenge.

Those themes play out differently in the book’s first chapter, which takes place in the uncomfortable city apartment of Hannah née Bloch, a middle aged woman whose family was put in a Nazi camp in German-occupied Poland and was later exiled to France.

Hannah’s story, of a Jew in the diaspora, is the most familiar here. By type, from birth, she lives in exile. Hannah suffers. She pinches pennies; she rarely leaves her run-down apartment. She is a kind of walking dead. But certain tactile things trigger her heart to swell, if only momentarily. In these moments, she touches her childhood, before the war — the last time she saw her father. She cleanses herself according to Jewish custom, she prepares a Sabbath meal, she lights candles and the light filters through the fingers she holds in front of her face. Once, she traveled to Israel, and in the Old City of Jerusalem allowed herself to become intoxicated by the bazaar. The sensations, smells, and visions carried her to Poland, which she couldn’t otherwise remember, and she fainted. She tells this to Hadrien while they travel on a city bus.

When they return to the apartment, they eat pistachios and Hannah recalls her childhood. Her father died in the work camp, but her mother, who she argues with every day on the phone, endlessly, wouldn’t ever admit he was dead. “Everyone in this family lived on the back of the disappeared man,” she tells Hadrien, “on the ruins of his death and, finally, on the spot occupied by a living person we couldn’t bury.” She’d never forgiven the betrayal. Her mother, she says, failed to teach her how to “face up to death, to affirm life.”

At some point, as an adult, she forced herself to stop believing her father would return. This was her only revenge against her mother. Hadrien watches her pray in the light of the candle, “an infinite grievance between her teeth.” She tells herself to gaze forward, there’s more to live. But, Larouche reminds us, our thoughts, like the dead, are restless. They badger us into isolation and then they never let us alone.