1.

Andrew Durbin is the director of the 2000 thriller drama The Beach, starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Tilda Swinton. Midway through the film’s premiere, Durbin cradles Leo as the multimillionaire actor sobs on the floor of the theater’s bathroom, totally unmoored by his own performance in the film. Then Durbin stands on a sidewalk with Tilda Swinton, watching the distraught Leo pull away in a towncar. Earlier, Durbin was standing on a sidewalk, watching a grievously-offended Katy Perry pull away in a Bentley. Earlier, he was being jerked off by his friend while watching Clueless, just a few pages after pitching the film The Canyons to a television producer. Later, he will be at the Frieze Art Fair, but only briefly. Then he will buy a Multistrada 1200 for Ciara.

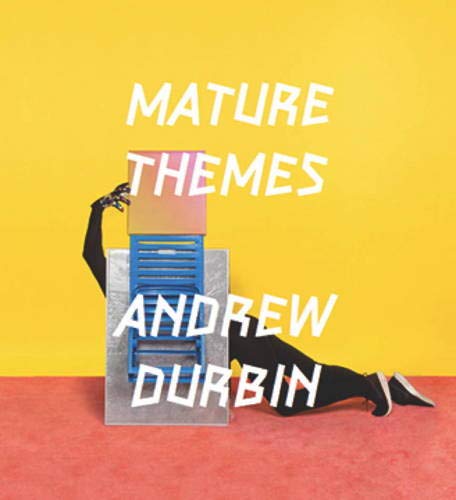

With company like this, you may be surprised that you don’t know of Andrew Durbin. Don’t be. Firstly, he’s young—in his mid-20s. Secondly, most of this isn’t true. Danny Boyle directed The Beach; Durbin has almost certainly never met Ciara, let alone bought her a motorcycle. Lastly, it doesn’t particularly seem like he wants to be known. His first full length book—Mature Themes, a collection of prose, poetry, and essays—doesn’t draw a cohesive biographical character so much as barrage its reader with an array of technicolor scenes, replete with camera flashes, expensive art, and totally fictional anecdotes about celebrities. It can seem, at first, a little overwhelming. So let’s start with what we do know.

2.

Durbin was raised in South Carolina. In 2008, he moved to the Hudson Valley to attend Bard College, where he studied poetry and the classics. During the end of his time at Bard, he began spending less time in the Hudson Valley and more time in New York City, two hours south of the college.

In October of 2011, a few months after graduating, Durbin and the poet Ben Fama began to put together something they were calling “Wonder.” It was first conceived as a series of “crush parties”: Invitees would be asked to email Durbin and Fama with the names of their crushes. The crushes would then be invited, and their names posted on Wonder’s tumblr. Once they’d been invited, they could invite crushes of their own. Soon, there’d be a full party roster of people brought together by desire, nervousness, and implicit, anonymous propositions.

They threw the first crush party in January of 2012. It was an immediate success—and not just as a party. As Jeff Nagy wrote in the fourth issue of online poetry journal The Claudius App (under the pseudonym “Jacqueline Rigaut”):

This at a time when perhaps the most perversely clever reading of poetry involved no reading whatsoever, when Wonder Books’ pair of “Crush Parties,” by physically aggregating the same social networks that would typically aggregated be by [sic] a reading, but by releasing those networks from the tedious need for poetry as a social lubricant, created perhaps the first pure works of Poetry 2.0, catching the reading up to the opening, as a social space in which the less one says about the art (there to perform its lubricating function and be ignored) the better–at last.

Despite the acerbic undertone of Nagy’s bad-faith endorsement, it shouldn’t be mistaken for a condemnation of the parties themselves. The scene that Nagy is satirizing, in which culture vultures collect around art and poetry as an occasion for schmoozing rather than as catalyst for serious discussion and serious thought, isn’t a tradition to which the Crush Parties were blindly submitting. On the contrary, by creating an occasion explicitly geared to romance, sex, and social climbing, Fama and Durbin were effectively instantiating the way these desires were encoded in contemporary poetry (and at the readings thereof). Think of it as a sort of “de-theorization,” the transmutation of a supposedly-base subtext into a democratized good time.

Concurrent with the planning of the first Crush Party, Durbin began working with the poet Paul Legault on a full-length work which would later be published by Wonder under the name Mall Witch. (On the Wonder site, Ben Fama is accredited as the author of Mall Witch; Durbin, Legault, and the poet/designer Joseph Kaplan as “producers.” However, at a reading at Berl’s Brooklyn Poetry Shop in the fall of 2013, Durbin said that he was the book’s real author, and that Fama had “nothing to do with it.” The truth is neither clear nor terribly important.) Around that time, Durbin and Fama also co-wrote “♥ This Will End In Tears ♥,” a chapbook-length “weird translation of Rimbaud,” which was distributed to the first fifty guests at the second Crush Party in April of 2012. For the third party, they published “The Story of a Stolen Kiss,” a chapbook by Bay Area poet Kevin Killian.

Concurrent with the planning of the first Crush Party, Durbin began working with the poet Paul Legault on a full-length work which would later be published by Wonder under the name Mall Witch. (On the Wonder site, Ben Fama is accredited as the author of Mall Witch; Durbin, Legault, and the poet/designer Joseph Kaplan as “producers.” However, at a reading at Berl’s Brooklyn Poetry Shop in the fall of 2013, Durbin said that he was the book’s real author, and that Fama had “nothing to do with it.” The truth is neither clear nor terribly important.) Around that time, Durbin and Fama also co-wrote “♥ This Will End In Tears ♥,” a chapbook-length “weird translation of Rimbaud,” which was distributed to the first fifty guests at the second Crush Party in April of 2012. For the third party, they published “The Story of a Stolen Kiss,” a chapbook by Bay Area poet Kevin Killian.

These initial publications marked Wonder’s transition from party series into the full-fledged press it is today. Over the three-odd years of its existence, it’s been responsible for a number of chapbook and full-length books, and has organized and facilitated a number of readings in New York. In 2013, the Wonder editors publicly declared that they’d be relocating to Los Angeles in 2015. In 2021, Wonder will, apparently, disband—they’re giving themselves 10 years. But to do what?

3.

Ambiguity—perhaps even duplicity—plays as large a part in Durbin’s biography as it does in his writing. Is Wonder actually going to move to Los Angeles in 2015? Or is it just the protracted set-up to a punchline that will, in all likelihood, never come? Did Durbin actually do any of the things he describes in the confessional prose-poetry-essays that make up Mature Themes, or is the entire thing a fabrication?

This distinction could very easily be frustrating—or, even worse, boring. In Mature Themes, it is neither. Durbin breezes right past the temptation to coyly stimulate the ambiguity of his anecdotes, thereby preventing his writing from getting bogged down in dull questions of fact versus fiction. As the narrator for each of the episodes depicted in the book, he comes across as an earnest, articulate friend, someone warm and known, thrilled to be enthusing, never stumbling into cynicism or lazy conclusions. This hyper-engaged flâneur is our Virgil for the cavalcade of top 40 pop, Food Network détournement, and Baudelaire recastings that make up the meat of Mature Themes, keeping us calm and informed. A lesser book moving through the same territory would stake its worth on the frisson that results from reading about tabloid-cover names in dinner-party situations. Durbin uses that, but only as grist for his seductively comprehensive theorizing on the forces circulating underneath each strip of celluloid.

Although the use of celebrities in fiction has been a popular trope in alt-lit-associated writing over the past few years (thanks largely to Tao Lin’s novella Richard Yates), Durbin’s writing bears little resemblance to that of those poets. Instead, his clearest influences come from the art worlds of New York and Los Angeles, and the poetry and prose that’s made a space for itself in systems that are historically more sympathetic to visual or conceptual art than to writing. For instance, he’s frequently cited the poet Eileen Myles’s The Importance of Being Iceland as being “central to [his] understanding of critical writing’s possibilities.” The lineage is visible: Durbin’s wry, inconspicuous humor and canny-outsider affect is very much of a type with Myles. The poet and artist Etel Adnan is another figure whom Durbin has frequently cited and occasionally written on; although her influence on his writing is less explicit than that of Myles’s, there are times (most notably in “Landscapes Without End” and “Sir Drone”) when Durbin moves into a descriptive register that’s reminiscent of Adnan’s work. And I’d be remiss not to mention the art-pop musician Ariel Pink, whom Durbin explicitly namechecks in “Monica Majoli.” Much like Durbin’s writing, Pink’s lyrics flit quickly between glitz, braggadocio, self-deprecation, and pained confessionalism, never firmly forming a knowable person. (It’s also worth noting that Ariel Pink released an album in 2012 that shares a title with Durbin’s book.) There are also a number of younger poets with whom Durbin shares a sensibility—for instance, Trisha Low, Juliana Huxtable, Kate Durbin, Lonely Christopher, and Lucy Ives, many of whom have published or read through Wonder.

Although the use of celebrities in fiction has been a popular trope in alt-lit-associated writing over the past few years (thanks largely to Tao Lin’s novella Richard Yates), Durbin’s writing bears little resemblance to that of those poets. Instead, his clearest influences come from the art worlds of New York and Los Angeles, and the poetry and prose that’s made a space for itself in systems that are historically more sympathetic to visual or conceptual art than to writing. For instance, he’s frequently cited the poet Eileen Myles’s The Importance of Being Iceland as being “central to [his] understanding of critical writing’s possibilities.” The lineage is visible: Durbin’s wry, inconspicuous humor and canny-outsider affect is very much of a type with Myles. The poet and artist Etel Adnan is another figure whom Durbin has frequently cited and occasionally written on; although her influence on his writing is less explicit than that of Myles’s, there are times (most notably in “Landscapes Without End” and “Sir Drone”) when Durbin moves into a descriptive register that’s reminiscent of Adnan’s work. And I’d be remiss not to mention the art-pop musician Ariel Pink, whom Durbin explicitly namechecks in “Monica Majoli.” Much like Durbin’s writing, Pink’s lyrics flit quickly between glitz, braggadocio, self-deprecation, and pained confessionalism, never firmly forming a knowable person. (It’s also worth noting that Ariel Pink released an album in 2012 that shares a title with Durbin’s book.) There are also a number of younger poets with whom Durbin shares a sensibility—for instance, Trisha Low, Juliana Huxtable, Kate Durbin, Lonely Christopher, and Lucy Ives, many of whom have published or read through Wonder.

In Mature Themes, Durbin has caught something dazzling, even bewildering. But readers who are willing to admit that it might be on their side will find it to be a warm, thoughtful escort through a world populated chiefly by cold objects. Katy and Leo might desert us at the end of the night, our favorite records might start skipping, and we might be left feeling a little tweaky once the lights come up in the theater. It’s even possible that we’ll never make it to L.A., or that there might someday be a final party, or even a final crush. But Durbin has found, for us, a sustainable optimism with which to navigate these tragedies; one which requires only that we think, remain, attend, and care. He has composed the most accurate portrayal that I can imagine of a life spent earnestly cathecting with everyone from Paula Deen to Joe Brainard, a life spent feeling enormously about all the things that will never feel about us. He makes it look awfully good, whoever he may be.