If the language of the pictorial arts is firmly lodged in descriptions of the narrative process — writers sketch out, paint, depict, trace, draw, color, outline — then the pictorial arts, in turn, seem to cry out for narrative, however doomed language ultimately is in its attempt to reproduce the particular alchemy of oil on canvas.

Among the most famous instances of narrative descriptions of art, or ekphrasia, are Homer’s description of Achilles’s shield in The Iliad, Rabelais’s characteristically bawdy, violent description of a mosaic depicting the god Bacchus rampaging through India, Auden’s consideration of the old masters, Wilde’s figurative and literal portrait of immorality and Robert Browning’s “My Last Duchess,” in which the Duke of Ferrara unveils the portrait of his unfortunate last duchess, she who was doomed by a blush:

Sir, ‘twas not

Her husband’s presence only, called that spot

Of joy into the Duchess’ cheek…

explains the jealous duke of his wife’s undiscriminating tendencies. A few dabs of red paint is all it takes to unloose the whole vengeful, deranged story, which makes the poem particularly illustrative of the ekphrastic urge to narrate, analyze, or recreate a given painting in another medium.

Sometimes this urge is so strong that it can compel an essay from even a half-remembered viewing. In his short piece on “Turner and Memory,” Geoff Dyer produces a typically sharp rumination on a particularly hazy Turner painting, <“Figures in a Building.” But as he admits at the outset: “I’m not entirely sure that this is the picture I am writing about.” What he does remember about the unfinished painting, an underground scene of darkness save for a revelatory “core of molten light” mysteriously radiating from some distant passageway, is precisely “the refusal of certain artworks to be reduced to memory.” Aesthetic rapture is experienced here as a half-remembered dream.

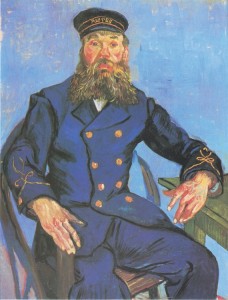

The same sense of thrilling uncertainty appears in another extraordinary and sui generis work of ekphrasis: Pierre Michon’s The Life of Joseph Roulin. “What can be done with him?” asks Michon in his novelized study of the postman with a “sultan’s beard” immortalized in several portraits by Van Gogh. And yet after reading a few pages of his luminous novella about Roulin’s portraits, a better question is “What can’t be done with him?”

Considering the contradictory renderings of the man Van Gogh drank with and painted in Arles, Michon confesses at the outset that Roulin is “a character of little help when one is foolish enough to write about painting.” Reservations aside, Michon soon launches into an ecstatic, incisive foolishness, losing himself in the “entire forest” of Roulin’s beard as he fleshes out the postman’s life. Roulin, Michon decides, is “a minor character in a Russian novel who’s forever hesitating between the Heavenly Father and the nearby bottle;” he is “the devoted muzhik, the grumbler, driving his boyar’s [Van Gogh’s] sled onward with strong prayers and mild impieties;” his “sacred cap” seems like it belongs to “some sort of icon, some saint with a complicated name, Nepomucen or Chrysostom.” Roulin is also an “outlaw prince,” nurturing beneath his civil servant exterior a love of the ferocity and “impeccable savagery” of the French republic’s violent origins.

If Michon’s imaginative exercise demonstrates anything, it’s that language can indeed hold its own against the vibrant swirl of Van Gogh’s brushstrokes:

I want…words [to] end up sprouting beards; they’ll appear in Prussian blue; they’ll be alcoholic and republican; they won’t make sense of one drop of the paintings; but with some luck, or by kidnapping, perhaps words will once again become a painting; they’ll be muzhik or boyar as the spirit moves me — and completely arbitrary, as usual—but will come visibly to light, manifest, and die.

Rimbaud’s colorful letters from his poem “Voyelles” suddenly don’t look as appealing — beardless and sober as they are.

2.

Alessandro Baricco’s recently translated novellas, Mr. Gwyn and Three Times at Dawn, published in a single edition by McSweeney’s, don’t rise to the ecstatic heights of Michon’s study, but together they constitute a sly, atmospheric work about copying a fine arts method. Baricco is less concerned with forging a new language worthy of painting than with dramatizing an artist attempting such a feat. Chronicling a fatigued writer’s efforts to reinvent himself as a copyist, a profession that he himself admits doesn’t properly exist, Mr. Gwyn and Three Times at Dawn are the portrait and self-portrait, respectively, of a linguistic portraitist.

After publicly renouncing novel writing, the successful British writer Jasper Gwyn comes across an exhibition of paintings, “large portraits, all similar, like the repetition of a single ambition, to infinity.” Staring at the nudes, each “unfit for nakedness,” he is moved by the artists’ ability to “take home” the subjects, so much so that he decides on a new profession for himself as an executor of a new kind of written portrait:

It wasn’t a real profession, [Jasper] realized, but the word had a resonance that was convincing, and inspired him to look for something precise. There was a secrecy in the act, and a patience in its methods — a mixture of modesty and solemnity. He would not like to do anything but that: be a copyist.

That mixture of modesty and solemnity suggests that Gwyn is thinking of the medieval manuscript tradition, secluded monks preserving the wonders of Western thought — without, presumably, what must have been the soul-crushing boredom of such an endeavor.

But there is another, etymological explanation for Gwyn’s attraction to the profession and model of “copyist.” Copyist derives from copia, “to write in plenty,” that is, to write over and over again. The great Renaissance scholar Erasmus wrote a little primer on copia, or the abundant style as he calls it. While warning of the pitfalls of such a style, which he defines as “richness is subject matter and expression,” he generally lauds the stylistic and argumentative advantages of expansion: “The speech of man is a magnificent and impressive thing when it surges along like a golden river, with thoughts and words pouring out in rich abundance.” (An eloquent defense to be deployed when accused of being a windbag.)

Even before he knows precisely what this new vocation entails, Gwyn begins to prepare, by attuning himself to the “luxurious rhythm” and “elegant slowness” of life, “concentrating on every single gesture” and running his hand over the surfaces he encounters to “[rediscover] the infinite range between rough and smooth.” In other words, he must tap into the fullness of life so that he can somehow convey the fullness of the people he wishes to copy: it is an apprenticeship in copia.

Guided only by a vague sense of what he wants, Gwyn chooses a studio according to his specifications (high ceilings, unfurnished, exposed old water pipes, scraps of wallpaper clinging to the walls, a swollen wooden door), commissions a musical composition from a famous avant-garde composer to be played on loop, and orders artisanal “Catherine de Médicis” light bulbs custom-built to emit a “childlike” color and burn out after a period of time. Gwyn’s preparation of his studio is hypnotic, and Baricco’s flat style — the same which creates the hallucinatory effect of his previously translated novel, Silk — nicely captures the trancelike state of an artist compelled by a vision he does not yet understand. In this way, Gwyn resembles the recreating hero of Tom McCarthy’s Remainder, who finds similar satisfaction in reproducing scenes from an apartment building down to the wafting smells of slightly burning bacon.

Guided only by a vague sense of what he wants, Gwyn chooses a studio according to his specifications (high ceilings, unfurnished, exposed old water pipes, scraps of wallpaper clinging to the walls, a swollen wooden door), commissions a musical composition from a famous avant-garde composer to be played on loop, and orders artisanal “Catherine de Médicis” light bulbs custom-built to emit a “childlike” color and burn out after a period of time. Gwyn’s preparation of his studio is hypnotic, and Baricco’s flat style — the same which creates the hallucinatory effect of his previously translated novel, Silk — nicely captures the trancelike state of an artist compelled by a vision he does not yet understand. In this way, Gwyn resembles the recreating hero of Tom McCarthy’s Remainder, who finds similar satisfaction in reproducing scenes from an apartment building down to the wafting smells of slightly burning bacon.

After having set up the apartment to his specifications, he studies his (nude) subjects for around 30 days for four hours each day, mostly in silence until he deems it right to ask them a question — one, we are vaguely told, is about laughing or crying. He then provides his well-paying subjects with a document, its paper and font and ink color and wrapping chosen with the same care as the artisanal bulbs. (In her review, The New York Times’s Rachel Donadio rightly mentioned Lucien Freud as an inspiration both for these fictional portraits and for Gwyn’s exacting methods.)

Gwyn’s first subject is a young woman who works for his literary agent and only friend. She is described in Ann Goldstein’s translation as “fat;” the original Italian, grassa, is similarly blunt. Not, in should be noted, rubicund, fleshy, or Rubenesque. Each of Gwyn’s subsequent sitters is cursorily introduced in the same clipped way; it is in Gwyn’s executed portraits, the contents of which are never divulged, that he will aesthetically flesh out the subjects. We only witness their reactions: intense gratefulness at receiving written versions of themselves that capture the full range and expression of their bodies and personalities.

The mystery of what the copyist produces is finally and neatly resolved, though the way Baricco explicitly accounts for the portraits’ emotional power in Mr. Gwyn’s closing scene slightly diminishes the novella’s seductive reticence. Indeed, the second novella, a triptych of scenes meant to demonstrate Gwyn’s unique style of portraiture, has its moments, but doesn’t quite explain all the fuss. Sometime a portrait is more alluring described rather than displayed.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons