1.

Much reading of personal history — whether it’s a memoir, a history, even poetry — evokes an awkward mixture of feeling: good writing affords pleasure, yet when it records real pain and despair we may feel guilt at our own pale, vicarious suffering. No human experience has produced such a rich literature of commingled aesthetic gratification and sympathetic misery as the Great War.

Up and down Britain in August 1914, thousands upon thousands of literarily inclined young men volunteered, their heads filled with rousing warlike poetry and dreams of leading a heroic charge, only to be mowed down by machine guns, or else survive years hunkered in the mud, shells bursting overhead, to produce the first great anti-war poetry. Or so the traditional narrative, bemoaned by historians but enduringly popular, goes.

Yet the soldiers’ responses to their experiences were diverse, complex, and — for the first time — profusely and skillfully recorded. History is in constant danger of being smothered under its own weight, the known course of future events squeezing the life from earlier moments that had been lived with possibility, the familiar story retold until we only remember the parts that fit its conclusion. But how did those idealistic fools become those bitterly wise poets? And did they all, really? With the centennial of the war almost upon us, wouldn’t it be interesting to re-read the war from the beginning, rather than looking back down upon it from the height of all of our learned interpretations?

What if one were to read heaps of personal histories all together, following perhaps a few dozen of the most rewarding writers from the beginning of the war to the end, at a distance of exactly a century? It could be a chorus of many different voices, a symphonic literary history. This idle thought became a big project, acenturyback.com, a blog that will slowly build into a new way of reading — or re-experiencing, in real time — the Great War: every day a piece of writing produced a century ago, or a description of events befalling one of the writers on that day.

Hard on the heels of the idea came a dirty little ambition: I wanted to discover a previously unrecognized coincidence. If I was going to read a hundred memoirs, I should find two poets passing in the night on some doomed trench raid, and no scholars yet the wiser. Perhaps I still will. But it turns out — although it’s only June and Franz Ferdinand is still safe and sound—that the centennial of a poetic overlapping is already upon us.

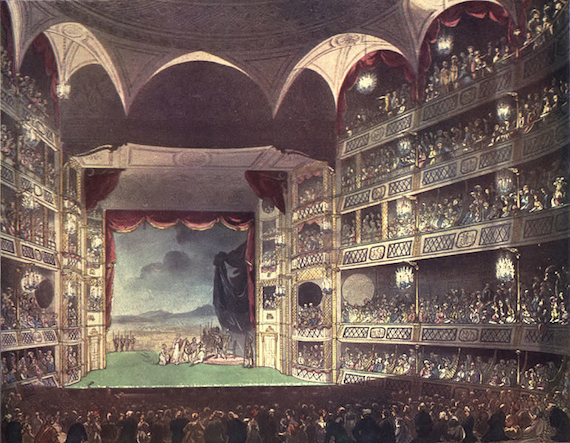

A century ago tonight, June 23rd 1914, was the London premiere of the Ballets Russes’ La Légende de Josephe at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. Amongst the throng of aristocrats, Gilded Age millionaires, and society hangers-on were — unbeknownst to each other and, apparently, to historians — three men with poetic aspirations. Each had some idea that they needed to make a change, but none knew that this was one of the last gorgeous, oblivious nights before old Europe tore itself apart.

All coincidences are “mere” coincidences, but this one can be put to good use. Read together, the three stories become a sort of prologue in a minor key to the guns of August, a rare composite view of that Last Summer — and of how it was remembered, and written.

Portrait of the poet Siegfried Sassoon by Glyn Warren Philpot (1917)

2.

As a matter of good history — history as it really was — the summer of 1914 was a time like most others. People went about their pleasure and their business, and most believed that common sense and the profit motive would keep a lid on international tensions.

Siegfried Sassoon, who had recently rented a flat in London, was preoccupied with nothing more momentous than his stalled personal progress. He was twenty-seven, had left Cambridge without a degree, and never held a job, and he had lost money on each new volume of flowery and outdated verses — a gentleman flâneur, or, in plainer contemporary idiom, a slacker. He now planned to live off of family money while working hard on his poetry, yet he was so unproductive and so short on funds that he would give up the flat in July and return home to Kent. Poetry remained a calling, but, until Sassoon’s muse awakened under fire, literature was far from a career.

Strangely, the war would transform Sassoon first into an aggressive fighter — he won the military cross “for conspicuous gallantry during a raid on the enemy’s trenches” — and then into the author of now-canonical protest poems. But it was his public refusal to return to action — motivated by his belief that soldiers were needlessly suffering for unworthy and ill-defined political goals — that would bring him an unusual fame. Instead of being punished, Sassoon was treated for “shell-shock” and eventually chose to return to combat.

In June 1914, however, none of this had yet come to pass. Sassoon was adrift, but he had found his way under the wing of Eddie Marsh, private secretary to Winston Churchill and ubiquitous fixer-and-connector of London’s young painters and poets. Marsh bought or published their work, fed them, even put them up in his spare room — come August, his day job would make him all too useful for poets in search of a military commission.

By day, then, Siegfried mooned about London, pretending to work or taking aimless strolls (he was mortified to run into a lonely, elderly friend at the zoo…two days in a row). As for the evenings, he had scant acquaintance with opera and none with the ballet, but he could follow directions. On the afternoon of June 23rd, as Sassoon later wrote:

I had now reached what appeared to be the zenith of my London season. For I was hurrying home to boil myself a couple of eggs and thereafter to emerge in full evening dress to attend a Gala Performance of the Russian Ballet…

…What the Russian Ballet would be like I had no notion… [I had said to Eddie Marsh] that I wasn’t particularly keen about ballets because nothing much ever seemed to happen in them…His pained and reproachful retort — ‘But it’s simply the most divine thing in the world!’ had given me the needed stimulus, and I’d made a start by securing a central stall for the London première of The Legend of Joseph. This I obtained by luck — the box-office chancing to have a returned ticket when all the seats had been sold. Richard Strauss, who had written the music, was to conduct, and a youthful dancer named Léonide Massine would be making his début.

This is impressive ignorance, given that the Ballet Russes, under Diaghilev, were scarcely a year removed from that quintessential succès de scandale, Le Sacre du Printemps. Although Sassoon was soon hooked on ballet, his account of the evening focuses (as much of his memoirs do) on his inexperience and his anxiety about his social position.

It was rather as if I had arrived uninvited at an enormous but exclusive party. Borne along by the ingoing tide of ticket-holders, I seemed to be surrounded by large smiling ladies with bejewelled bosoms who looked like retired prima-donnas and whose ample presences were cavaliered by suave grey-haired men who might possibly be successful impresarios. They all seemed to know one another…

Sassoon goes on to describe the post-performance posing of London’s glitterati:

Eddie Marsh being the only person among the scintillating audience whom I had any likelihood of knowing, I now set out on a self-conscious cruise in quest of him. Before long I caught sight of him standing at the top of a flight of steps. He was in monocled conversation with a couple of brainy-looking young men in dowdy dinner jackets, to whom I was introduced without quite grasping their names.

One of these young men, “in that see-saw intonation which has since become known as ‘the Bloomsbury voice’” snarkily opined that the “décor was surely Berlin-Veronese at its most meretricious.”

Poor Sassoon! Out of his depth among such cognoscenti, he “duly assimilated the word ‘daycore’” and went home “feeling a bit lonely.”

The funny thing is that one of those names he couldn’t quite grasp may have been “Osbert Sitwell.”

Osbert Sitwell as Apollo in Boris Anrep’s “The Awakening of the Muses” (1933)

3.

Osbert Sitwell was then only twenty-one, another aimless scion of moneyed country gentry with a troubled family history. This family was both much grander — Osbert would eventually succeed his father as the fifth baronet Sitwell — and more comprehensively screwed-up: Lady Ida had recently been imprisoned for fraud, and Sir George, was so thoroughly eccentric that he exceeded even the standards of the English aristocracy in off-hand cruelty toward his children.

Yet privilege has its privileges, and Osbert knew many of the “best” and richest people in society, who provided him with a smooth entrée into the world of high art. For Sitwell, 1914 marked his personal discovery of avant-garde art. By the time June rolled around he had spent his allowance and gone deeply into debt, but he was no longer aimless — he knew that he wanted to make a career in Modern art.

The one thing he didn’t want to be was a soldier — which, of course, he was. His father had decided, several years before, that Osbert needed what we might now call “more structure.” So, naturally, he arranged an army commission, without — in Osbert’s telling — his son knowing a thing about it. Which is very hard to believe. In any event, the younger Sitwell was now an officer in the Grenadier Guards, a position that did indeed provide structure, just not quite enough: his occasional changing-of-the-guard duties before Buckingham Palace left plenty of time for artistic exploration and social mountaineering.

When the war begins, then, Lieutenant Sitwell will see combat much sooner than most. He, too, was moved to verse by his months on the Western Front, although his war poems are few and relatively slight. Still, as uniformed literary gadflies, it was natural that he and Sassoon would (again) cross paths, and they did indeed became friends. In the summer of 1918, Osbert will even host a lavish lunch for Sassoon and Wilfred Owen. Sitwell and Sassoon worked together on anthologies and journals after the war, but Osbert and his siblings (the future Dame Edith and their younger brother Sacheverell) soon fashioned themselves into central figures of the Modernist movement. This all became too outré for Sassoon, who broke off the friendship.

But all this, again, lay in the future. Right now — a hundred years ago — Osbert was playing the Misfit Subaltern by day and gorging on high culture by night.

Sitwell was, both naturally and deliberately, a huge snob. He was also a self-mythologizer and a name-dropper. His memoirs are, therefore, very amusing to read, although as an entertainment rather than as capital-L Literature — they provide nothing like the carefully composed ruminations on memory and loss that make Sassoon worth lingering over. When Sitwell writes of 1914 he is seeking not to rediscover his callow younger self but rather to portray the young artist — and all of his famous artist friends — on the first rungs of their climb to greatness:

On June 23rd, I was present at the initial appearance of a great new dancer… Massine…in after years a valued friend of my brother and myself. La Légende de Josephe, in which he first danced, had been designed as a spectacle, rather than a ballet, to the music of Richard Strauss. In it, figures costumed by Léon Bakst, and such as might have been portrayed by the brush of Paolo Veronese, feasted in an enormous scene, pitched, at a hazard, halfway between Babylon and Venice…

That very same comparison to Veronese! Could Sitwell, then, have been the languid blueblood that overawed Sassoon with his description of the “daycore”? It certainly sounds like him.

Or could this be a clue to a literary conspiracy? Is Sassoon referring to Sitwell without using his name, twitting his pretensions with a memory dating from before their friendship? It would be tempting to think so if it were not so completely out of character for Sassoon — or, rather, so against the grain of the polite, fervently inward personality of the narrator of his memoirs.

Did Sitwell, then, remember meeting Sassoon? He should have: Sassoon came from a disinherited branch of a famously wealthy family. He considered himself more a Kentish Thornycroft than an exotic Jewish Sassoon, but new acquaintances often assumed that he was one of those high society Sassoons. How could Sitwell fail to mark a man with such a noteworthy name? Yet, by the same token, if he had remembered it he surely would have dropped it for us. So, alas, they were probably not introduced that night.

And yet they may have come very close indeed. Bear with me for a moment.

Sitwell is at pains to tell us that, while he immediately recognized these new geniuses, most of the true artists in London were not yet clued in to the ballet. (This is a silly claim, since we can now put two other poets there that night, and it is likely that Rupert Brooke came to the next performance.) Nor did “the nodding tiaras and the white kid gloves” who did attend — and pay for — the spectacle understand what they were seeing. But, since the rich do throw great parties, Osbert Sitwell, who spans both worlds like a foppish colossus, will now jauntily slide from lecturing us on Important Art to gossiping about the biggest after-parties of the season, affairs hosted by the likes of Lady Ripon, Lady Cunard, and Lady Speyer, at which Debussy and Diaghilev rubbed shoulders with London’s elite.

It was to Lady Speyer’s vulgar nouveau riche mansion (oh yes indeed — the description is Sitwell’s; he also calls Lady Speyer “lacking…in the power of self-criticism” and fails to mention that she had been an accomplished professional violinist) that Strauss brought a Tyrolean band, to the annoyance of her neighbors. Let’s return now to Sassoon, lonely and headed home:

On my way out of the theatre it had seemed as if everyone except me must be ‘going on somewhere else’. In the foyer there had been a conspicuous group of young people… one of them had rapturously exclaimed that ‘the party was sure to be marvelous fun and food’. Handsome and high-spirited, they had made me wish that I were going with them, even though they were behaving as if they’d bought the whole place. If I were a real rich Sassoon I should probably have been one of them, and should have talked to titled ladies in tiaras and bowed to ambassadors in boxes.

Even the tiaras! And why wouldn’t the ambassador attend a premiere conducted by a famous German composer? And what could be more natural than that Lady Speyer — titled, surely tiara’d, and, though American by birth, the daughter of a German officer and the wife of a financier of German-Jewish ancestry—would later play host to both?

When Siegfried, then, is home alone, reflecting that “somewhere in that London summer night a grand party was being given in honor of the famous German composer to whose applause I had contributed my clapping,” it’s likely that Osbert is hanging about that very party.

If he was, the coincidence is so sharp that it seems like a new sort of historical irony, an actual historical accident that out-writes the best writers. Instead of two separate stories of a young man and the ballet, we now have a stereoscopic image of two poets nearly colliding, then going on their way, one borne off with the society swells, the other headed home to wallow in loneliness and think of poetry. This is even better “Last Summer” spin than Sassoon’s song of his own innocence or Sitwell’s clever invocation of Venice and Babylon — cities famous, respectively, for over-decorated decline and ruinous fall — as he segues from disappointing ballet to uproarious party.

And yet: the very end of Sassoon’s chapter pulls us back to this moment. What is his younger self thinking, lying in bed that night?

“Better for youth to be falling asleep with a snatch of Papillons still dancing in his head than to be acquiring disillusionment in that dazzling limbo of the coldly clever, the self-seeking, and the faithless.”

Was this thought thought in 1914, or placed in an innocent 1914 mind by the experienced, memoir-writing man more than a quarter-century later? By then Sassoon had long been committed to writing in a backward-looking pastoral style that can be read as an extended rear-guard action against the onslaught led by the Sitwells, a fighting retreat in defense of the traditional decencies of English poetry. Damn those cold, self-seeking Sitwells: and perhaps the pendulum should begin to swing back from skepticism and coincidence toward credence and conspiracy…

Edward Thomas, circa 1905

4.

This return to good English nature poetry can carry us to Edward Thomas, whose life was then so different from either Sassoon’s or Sitwell’s that the roles of social butterfly and melancholy poet seem suddenly like child’s play. Thomas was thirty-six, living in a country cottage with his three children and his heroically supportive wife Helen, whom he no longer loved. They had married young — and pregnant — and though each came from the educated middle class, they had been legitimately poor, their lives hard. Thomas struggled for years to support his family with his writing, and although he survived bouts of crippling depression to produce dozens of books of criticism and nonfiction — much of it written in swift, striking prose — he saw this as hack work that had prevented him from writing something lasting.

Thomas felt like a failure. Yet when he was reasonably healthy he realized he was lucky not only in his wife but in his friends. These included several of the “Georgian Poets” — their work recently anthologized by Eddie Marsh — who had settled near the village of Dymock, Gloucestershire. Thomas at times participated in their unique version of ad hoc communal living, which seems to have been something like a half-realized William Morris tract: long walks and arguments, spurts of agricultural labor, children and guests running freely through various houses, and many perplexed stares from the locals.

Thomas believed that the poetry of the Edwardian age was tired and in need of a new direction, and he found confirmation of this in the poetry of Robert Frost, who had brought his family to England in 1912 and later rented a house in the same area. Frost and Thomas soon became fast friends, not least because of the hand-in-glove match between Frost’s new work and Thomas’s theories about the need for a more natural poetic idiom—later this summer Thomas will be giving Frost’s North of Boston several rave reviews.

A few weeks before the night of the premiere, though, he had done something courageous, considering his personal demons: he had confessed, in a letter to Frost, that he, too, wanted to be a poet. Thomas had only dabbled in verse before, but he too was close, now, to turning away from a disdained career and rededicating himself to poetry. It took a few months, but by early 1915, even as he began to feel crippling pressure to enlist, poetry was flowing freely from Thomas’s pen.

And then he did enlist, and went to war, and was killed by a heavy caliber shell on Easter Monday, 1917. There are scarcely two years between the first poem and the last, but this was enough time for Thomas to emerge as a major poet.

Thomas based several of his first poems on observations jotted down in notebooks during the summer of 1914. In fact, the trip to London to see the ballet (though not the ballet itself) ended up providing the kernel of his most beloved poem.

Another friend of Thomas’s now enters the story — Eleanor Farjeon, a poet and a quiet sort of free spirit who later became a prolific author, largely of children’s literature. She had met Thomas not long before and fallen in love with him. He, it would seem, valued not just her friendship and critical faculties but something in that love itself. This should be the beginning of a bad story. But it’s not — only a strange one. Eleanor frequently stayed with the Thomases, and her feelings were obvious. But Helen Thomas seemed to believe that, since Edward showed no sexual interest in Eleanor, the disproportionate attraction would strengthen the family bond rather than strain it. Eleanor became a valued reader and editor of Edward’s work, and the two women remained friends long after the death of the man they had both loved, each writing memoirs. In Edward Thomas: The Last Four Years, Farjeon includes several of the letters Thomas wrote to her:

My dear Eleanor

We are just starting for Ledbury and are in a real hurry. Last night by the way we were at the ballet and one of the nicest things in that hot air was Joan Thorneycroft [sic] who transpired. Also Thamar, Papillons and Joseph which I liked in that order…

Helen and I are

Yours ever

Edward Thomas

So Edward and Helen Thomas, too, were in the audience at the Theatre Royal that night.

And what did he make of it? Well, not much—at least not directly. Who knows if he would have, like Sitwell and Sassoon, re-written a night at a “spectacle, rather than a ballet,” (the words are Sitwell’s) into a prime example of the artistic indulgences of the belle époque. It would have been hard to resist:

It included a magnificent banquet which was the most sumptuous spectacle I had ever seen; and altogether I felt that I’d got rather more than a guinea’s-worth of gorgeousness… it is possible that I unconsciously realized that The Legend of Joseph—as was generally admitted afterwards—had been rather a heavy affair—a grandiose failure, in fact. The date of its production subsequently suggested that Belshazzar’s Feast would have been a more appropriate subject for everyone concerned. Many people must have looked back on that evening as ‘epitomizing the end of an epoch.’

This is Sassoon, who, when not focusing on his own experience, inevitably places the performance in the larger context of the Last Summer, alongside the heat, the parties, the preoccupation with Ireland and the Suffragettes, and the indifference, five days later, to news of the assassination of some Archduke somewhere.

5.

This is why a forgettable ballet can be so memorable: like any collective memory, it can be put to different personal uses. For Sassoon, it was at once an initiation and a confirmation of a wan sort of outsider status; for Sitwell, only one star-studded night among many; for Thomas, the gift of a trip to London—a night out, but also a day away.

And yet the ballet caused at least one ripple that did not subside into anecdote— Thomas did look back on that trip to London. They had to get back to the country afterwards, and the letter to Eleanor Farjeon, written from his parents’ house the next morning is perhaps the last thing he wrote before catching the train home. Later that day, stopped at an obscure village station, Thomas scrawled a few lines in his notebook:

Then we stopped at Adlestrop, thro the willows cd be heard a chain of blackbirds songs… looking out on grey dry stones between metals & shiny metals & over it all the elms willows & long grass—one man clears his throat—and a great rustic silence.

In January, Thomas returned to this notebook and wrote “Adlestrop,” one of the great poems of the English countryside. But it’s a poem of sense-memory, not immediate impressions, a look back from the war’s first winter at a vanished summer. Its four stanzas are the transmutation, by time, of simple observation into elegy.

Beginning “Yes, I remember Adlestrop,” the poet recalls that view:

And willows, willow-herb, and grass,

And meadowsweet, and haycocks dry,

No whit less still and lonely fair

Than the high cloudlets in the sky.

Thomas might not have loved his night at the ballet, and he did not live to write a memoir of those last days of peace—but he remembered Adlestrop.

6.

There is one final footnote to tack onto the historical record: Sassoon was wrong in thinking that Eddie Marsh was the only person he “had any likelihood of knowing” that night. The Joan Thornycroft mentioned in Thomas’s letter was engaged to Eleanor Farjeon’s brother—and she was Sassoon’s first cousin. Did she go along with Helen and Edward, or is it just possible that she attended with her cousin, “transpired” to say hello, and was later churlishly forgotten or mercilessly written out of Sassoon’s lonely-boy memory-story?

No—there’s no real reason to imagine such an odd omission. Besides, it’s much nicer to believe in the complete coincidence of Marsh, Thornycroft, Sitwell, Sassoon, and the Thomases coming altogether for an evening at the ballet—and in my being the first to notice.

A small world, and a salutary coincidence, a reminder, here at the centennial-season starting line, of the difference between the uncertain angularity of history as it is lived and the voluptuous story-shape of history as it was written up afterward. Looking back on June, what they wrote about was not a mediocre ballet but a last banquet of the doomed, not an ordinary London summer, but rather a lovely, sun-dappled paradise headed all-unknowing for total eclipse.

Notes for Further Reading:

The first thing to read would be the poetry: all three poets are represented together in many anthologies of First World War Poetry, including the newer Penguin and the Everyman, while both Sassoon and Thomas are published in manageable Collected Works (Sitwell’s verse is not worth sustained reading).

As for the memoirs, Sitwell may be a minor poet, but his five volumes of autobiography, beginning with Left Hand! Right Hand!, are certainly lively, if out of print. The third volume, Great Morning!, is quoted from above, while Laughter in the Next Room has several friendly anecdotes, from the post-war years, involving Sassoon. Thomas left no memoirs, but there are Helen Thomas’s, collected in Under Storm’s Wing, and Eleanor Farjeon’s Edward Thomas: The Last Four Years, from which the Adlestrop-day letter is quoted. The quotation from Thomas’s notebook is found in Matthew Hollis’s excellent Now All Roads Lead to France. All in all, Sassoon’s six volumes of memoirs, which appeared between 1928 and 1945, are the most interesting sustained literary wrestling match with the war. The first three are fictionalized in a very odd way (they can be found as The Complete Memoirs of George Sherston, and have recently been individually republished), while the next three go back to the beginning in a more open and literary way. The middle volume of this second trilogy, The Weald of Youth, contains the descriptions of the unfateful night at the ballet. For more on Sassoon’s unusual memoirs, see here—there are also short introductions to Thomas, Sitwell, Brooke, and Marsh.

As for the memoirs, Sitwell may be a minor poet, but his five volumes of autobiography, beginning with Left Hand! Right Hand!, are certainly lively, if out of print. The third volume, Great Morning!, is quoted from above, while Laughter in the Next Room has several friendly anecdotes, from the post-war years, involving Sassoon. Thomas left no memoirs, but there are Helen Thomas’s, collected in Under Storm’s Wing, and Eleanor Farjeon’s Edward Thomas: The Last Four Years, from which the Adlestrop-day letter is quoted. The quotation from Thomas’s notebook is found in Matthew Hollis’s excellent Now All Roads Lead to France. All in all, Sassoon’s six volumes of memoirs, which appeared between 1928 and 1945, are the most interesting sustained literary wrestling match with the war. The first three are fictionalized in a very odd way (they can be found as The Complete Memoirs of George Sherston, and have recently been individually republished), while the next three go back to the beginning in a more open and literary way. The middle volume of this second trilogy, The Weald of Youth, contains the descriptions of the unfateful night at the ballet. For more on Sassoon’s unusual memoirs, see here—there are also short introductions to Thomas, Sitwell, Brooke, and Marsh.

While I haven’t found anyone remarking upon the double coincidence of the three poets (Kirsty McLeod’s The Last Summer records both Sitwell and Sassoon’s comments on the ballet, but does not mention the fact that they seem to have gone the same night; I don’t think anyone has noticed that Thomas was there too) the obsession with poets crossing each other’s paths is harbored by many others—there’s even an odd book all about it (Harry Ricketts’s Strange Meetings). The most famous convergence of the poets is that of Sassoon—now playing the grizzled, urbane, and experienced hero/protester/poet—and the shell-shocked and as-yet-unpublished Owen at Craiglockhart War Hospital. This became the starting point for Pat Barker’s Regeneration trilogy, an unusually powerful intertwining of history and fiction.

While I haven’t found anyone remarking upon the double coincidence of the three poets (Kirsty McLeod’s The Last Summer records both Sitwell and Sassoon’s comments on the ballet, but does not mention the fact that they seem to have gone the same night; I don’t think anyone has noticed that Thomas was there too) the obsession with poets crossing each other’s paths is harbored by many others—there’s even an odd book all about it (Harry Ricketts’s Strange Meetings). The most famous convergence of the poets is that of Sassoon—now playing the grizzled, urbane, and experienced hero/protester/poet—and the shell-shocked and as-yet-unpublished Owen at Craiglockhart War Hospital. This became the starting point for Pat Barker’s Regeneration trilogy, an unusually powerful intertwining of history and fiction.

For a more careful consideration of the possibility that Sassoon remembers Sitwell’s presence and is covertly mocking him, or for notes on my far-from-exhaustive efforts to find previous references to this coincidence, see today’s entry on the A Century Back blog.