1.

Peter Parker was born in 1945 and grew up in Forest Hills, Queens, under the care of his uncle and aunt. Ben Parker was a gentle man. May was a doting but naïve caregiver. Peter was a prodigy and Ben and May Parker encouraged his scientific aspirations. It was a happy home, but at school Peter was the target of low-key verbal bullying and though an outside observer would have considered the taunts mild, they amounted to a form of abuse that haunted him well into his adulthood.

In the early 1960s, several young men and women in the New York City area gained superhuman powers thanks to a series of nuclear experiments held in violation of rudimentary safety codes. That was Peter’s story. He was at a certain place at a certain time and a radioactive spider bit his hand. Within 24 hours, his body underwent a metamorphosis. He was now faster, stronger, and more agile than most members of the human race and possessed a sixth sense which warned him of danger. He sewed a red-and-blue suit which showed off his new thin-muscled body, a body he was proud of and for which he had done nothing to deserve.

He entered and won a wrestling contest. He was a great success, but he was too young to appreciate his good luck. In a moment of self-absorption, he failed to stop a thief. By coincidence that criminal would later kill Ben Parker, and upon discovering the consequences of his selfishness, the teenager decided he would use his powers to help others. He invented webbing fluid, a potent but non-lethal weapon which allowed him to swing across the skyscrapers of Lower Manhattan and trap opponents in viscous nets. He became Spider-Man, an amazing addition to the New York skyline. A hyphen separated the two parts of his name.

2.

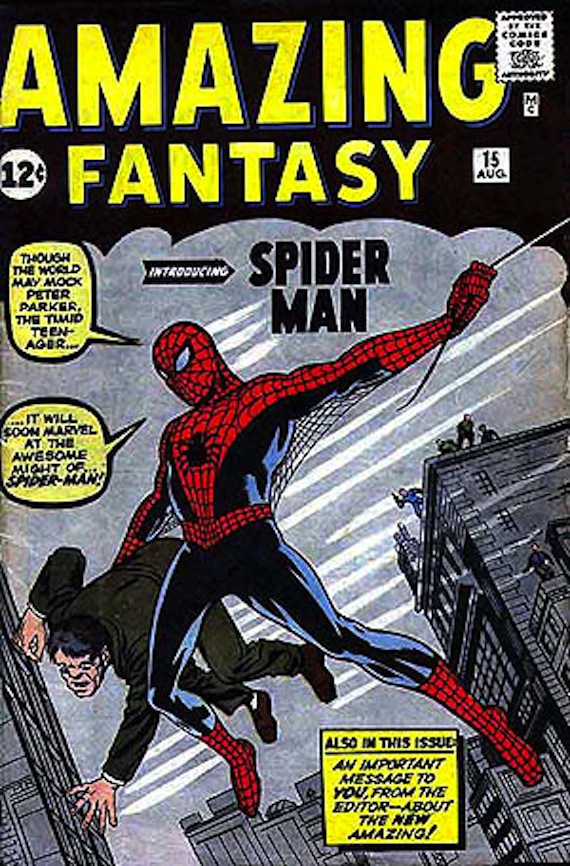

Stan Lee and Steve Ditko’s Peter Parker first appeared in Amazing Fantasy #15 in December 1962. In his debut, he was friendless, miserable, and smarter than everyone in every room he ever walked into. Ditko, a former horror comics artist, had learned to draw humans at their most vulnerable and grotesque and his Peter Parker was an attenuated figure, handsome but not too good-looking, a little damaged. In the pages of The Amazing Spider-Man Parker proved to be a very good superhero, but he wasn’t slick and that was part of his charm. “Isn’t there just a little of Peter Parker in all of us?” That’s the final line of The Amazing Spider-Man #27, from August 1965. In that issue, he loses his uniform and had to make do with a cheap version he picked up in a costume shop. Spider-Man lost his mask in fights. He also lost fights. He fought common colds while in the middle of fights. The superhero who could be you.

Peter Parker was Spider-Man for many reasons and not all of them could be named. He suffered an oppressive guilt for the death of his Uncle Ben, but guilt wasn’t enough for him to do what he did; Parker doesn’t even mention his uncle for three years following the origin story in Amazing Fantasy #15. The truth is that Peter Parker enjoyed being more powerful, better than his peers who made fun of him and better than the criminals he fought. His social circle knew nothing about his abilities, and he took an arrogant pride in his secret identity. He was a sadist, within limits. He never killed anyone, but he enjoyed humiliating and hurting his opponents, taunting them with one-liners — he was a Woody Allen fan but he lacked Woody Allen’s talent — and he rarely softened a punch even when fighting those he could crush with two fingers. He started fights with Johnny Storm, the good-looking member of the Fantastic Four and the subject of Parker’s envy and admiration. He was a narcissist.

He was also Spider-Man because he needed money. He sold photographs of his fights with criminal misfits and ugly men to J. Jonah Jameson, the publisher of Now! and The Daily Bugle, who wrote editorials prejudicing the general public against the young superhero. Peter’s freelancing helped his Aunt May survive her widowhood and earned him spending cash. But in the end, he was profiting off of violence, on fights that he sometimes started. He was also a dishonest journalist. After he failed to photograph a battle with Sandman, he restaged it using large piles of sand.

Yet he was, at heart, a good man and he suffered for his goodness. In Amazing Spider-Man #1 he flirts with the idea of crime in order to help his Aunt May save their house, but he eventually takes pride in his basic decency. He privately acknowledged the good in even his worst bully, Flash Thompson. He was devoted to his aunt. He continued his work as a vigilante even while facing a public that hated him. He honored that role no matter how much it disrupted his personal life.

He grew older, his posture improved, and he found himself in a series of relationships with beautiful women who noticed his charm and his blue eyes. But he was an incompetent and absent lover, more loyal to his secret identity than he was to his women, though he did save their lives on numerous occasions. In the context of the time, he was strangely under-eager to take advantage of the sexual revolution. His life as a superhero could be exhilarating, but it brought him only so much joy. He was a loner. He was also a lonely man.

Thanks to the open-ended, half-planned nature of comic-book serial storytelling, Lee and Ditko could discover new facets of Peter Parker’s psychology in small ways from one month to the next, allowing the man to contradict and amend himself to the point where his heroism was as strange as the anti-heroism of Walter White, his pop-cultural antithesis. John Romita took over for Ditko in Amazing Spider-Man #39 in August 1966 and completed Parker’s transformation into a romance-comics heartthrob, discovering the depression inherent in the young man’s doleful charm. So no, it’s not so much that Spider-Man was the superhero who could be you, though Lee used that very phrase in the comics. Spider-Man was one of the few superheroes who was more interesting than the supervillains he fought.

3.

Spider-Man and Peter Parker were inventions of New York, not the New York of our world, but a New York, despite all Lee and Ditko’s use of proper landmark names, that was as foreign as Metropolis or Gotham City. When Marvel Comics introduced a new Spider-Man in its Ultimate Universe a few years ago, one who had a black father and a Latino mother, the decision only highlighted one of the weirder elements of the world Lee and Ditko created 50 years before. Parker was a working-class teenager growing up in 1960s Queens and yet his social circle — Mary Jane Watson, Gwen Stacy, Flash Thompson, Betty Brant, Ned Leeds — did not include anyone with an obvious white-ethnic marker, an Irish, Italian, or Jewish name. The interior of Parker’s high school was based on the one Ditko attended in Johnstown, Penn. When Parker graduated high school he entered Empire State University, an amalgam of Columbia and City College, which again, oddly, had strikingly few non-white-ethnics. He mostly fought petty hoods who spoke like ’40s B-movie gangsters. Parker’s world was lily-white until issue #51 (August 1967), when Robbie Robertson, a black man, takes a city editor position at The Daily Bugle, and drug-free until issues #96 through #98 (May-July 1971), when Harry Osborn faces the consequences of his acid trips. And as much as he fancied himself an outsider, he was very much at home in his version of the city.

This New York provided a template against which Peter Parker, with all his self-doubts and all his angst, could invent himself. The superhero genre had existed for at least three decades before he showed up, and part of Parker wondered if he was a kind of Don Quixote, dressing up and playing out a fantasy for a world that did not need his heroism. But this particular New York did need him. The presence of supervillains, of the Green Goblin and Doctor Octopus, always prepared to kill thousands, suggested that this shadow New York was under constant threat of annihilation. In our world, Peter Parker would be a true madman. (Actually in our world, the U.S. government would have captured and held him in a terrible facility and re-engineered him into a super soldier. It also would have figured out a way to turn his webbing fluid into either a torture or lethal weapon on a massive scale. Imagine a giant thick substance designed to cover entire cities and suffocate all of its inhabitants.) But Parker challenged his homogenous version of New York and made it more interesting. In his New York, he could be a most beautiful man, like Don Quixote or Jean Valjean or Samuel Pickwick — Dostoevsky’s three famous examples of the archetype — a figure whose greatest creation, born out of neurosis and genius, is himself.

This is why he is loved. This is why you want to be him. And this is why he is not the superhero who could be you.

4.

The problem with Spider-Man is the same problem with all popular comics heroes. Eventually, after several hundred issues, he hit a moment of stasis in which he stopped evolving, stopped discovering the strange hidden facets of his personality.

Still, writers and artists attempted and sometimes succeeded in putting their signatures on Parker. In July 1973, Gerry Conway, Gil Kane, and Romita killed off Gwen Stacy in the middle of a fight between Spider-Man and the Green Goblin. There is a consensus among fans that she died from whiplash from the web Parker shoots to save her, thus providing a space for a new form of a guilt for Parker to explore. I was 10 when I got into reading my older brother’s collection from the late ’80s. That Spider-Man was still interesting. He was a college dropout, fighting to make rent, seriously wondering how he wasted his intellectual talents in the interest of crime fighting. But within a few years, after he married Mary Jane Watson, he ceased to be credible. In the early ’90s, Todd McFarlane’s artwork exaggerated Spider-Man’s contortionism, while his writing accentuated his sadism and diminished his wit, transforming one of the great geek heroes into a dumb jock. By the 2000s, the storylines within the regular Marvel continuity had achieved a level of absurdity that demanded retconning. In one limited series set in the future, Parker’s radioactive semen kills Mary Jane. Marvel writers in their attempts to be gritty, had become the equivalent of literary novelists who reach for Holocaust references as substitutes for gravitas. Their fascination with ultra-violence obscured the essence of Spider-Man.

Brian Michael Bendis and Mark Bagley’s Ultimate Spider-Man, which launched in September 2000, started everything over again, and attempted to return the hero to his roots. In Bendis and Bagley’s version, Parker was a millennial and his Uncle Ben and Aunt May were aging hippies. And Parker looked to John Hughes movies for inspirations for his one-liners. “It’s almost Shakespearean in the sense that the theme of it, the morality of it, all of it holds true,” Bendis told me in an interview that appeared in Ultimate Spider-Man: Ultimatum. “And you can change the setting, you could put it all on a space station and the story of Peter Parker getting bit by a spider would resonate all these ideas. So once I came to terms with that, that I’m adapting a work by Shakespeare, it became very freeing.”

Brian Michael Bendis and Mark Bagley’s Ultimate Spider-Man, which launched in September 2000, started everything over again, and attempted to return the hero to his roots. In Bendis and Bagley’s version, Parker was a millennial and his Uncle Ben and Aunt May were aging hippies. And Parker looked to John Hughes movies for inspirations for his one-liners. “It’s almost Shakespearean in the sense that the theme of it, the morality of it, all of it holds true,” Bendis told me in an interview that appeared in Ultimate Spider-Man: Ultimatum. “And you can change the setting, you could put it all on a space station and the story of Peter Parker getting bit by a spider would resonate all these ideas. So once I came to terms with that, that I’m adapting a work by Shakespeare, it became very freeing.”

Bendis and Bagley did capture Peter Parker’s morality. Their stories were cleanly plotted, Bendis’s writing was slick, and Bagley’s pen, and later that of Stuart Immonen who replaced him in the 111th issue (September 2007), looked more to Romita’s romance than Ditko’s horror ethos for inspiration. And yet that slickness and Peter’s unquestionable decency formed the title’s main flaw. Bendis’s Parker was a little too charismatic. The characters in the Ultimate Universe loved him more than any of the comic’s readers could. I liked the comic myself, but a true Spidey agoniste would have preferred the Peter Parker of the Ditko and Romita years.

Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man trilogy was a throwback to the Ditko and Romita years. All three of his movies, even the much maligned Spider-Man 3, have fine moments, though they spend far more time studying Peter Parker’s guilt than the other more disturbing aspects of his personality. Raimi’s horror-movie pathos turned Spider-Man’s villains into tragic figures. Alfred Molina’s Doctor Octopus, in his final moments, rediscovers a moral clarity and sacrifices himself in order to undo his evil plans. Thomas Haden Church’s Sandman attempts to grasp his dead wife’s wedding ring even as his fingers dissipate into tiny molecules. Tobey Maguire’s Spider-Man is sweet, naïve and gentle, and a fine presence, but he exists to counterbalance the weight of evil and age more than to exert his awesome self.

Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man trilogy was a throwback to the Ditko and Romita years. All three of his movies, even the much maligned Spider-Man 3, have fine moments, though they spend far more time studying Peter Parker’s guilt than the other more disturbing aspects of his personality. Raimi’s horror-movie pathos turned Spider-Man’s villains into tragic figures. Alfred Molina’s Doctor Octopus, in his final moments, rediscovers a moral clarity and sacrifices himself in order to undo his evil plans. Thomas Haden Church’s Sandman attempts to grasp his dead wife’s wedding ring even as his fingers dissipate into tiny molecules. Tobey Maguire’s Spider-Man is sweet, naïve and gentle, and a fine presence, but he exists to counterbalance the weight of evil and age more than to exert his awesome self.

Andrew Garfield’s Peter Parker in Marc Webb’s Amazing Spider-Man movies, themselves modeled on the Bendis/Bagley and the Bendis/Immonen runs, is the most physically interesting one we’ve seen on screen. He’s discovered the line between Parker’s teenage awkwardness and Spider-Man’s athleticism, Parker’s brooding charm and Spider-Man’s power, and beneath it all there lies his constant melancholy. He’s a young-adult hero with a riot of conflicting rages that recall those suffered by Lee and Ditko’s Parker. Working with a by-the-numbers screenplay, Garfield reimagines a beautiful man, a flesh-and-blood being, that otherwise would have been nothing more than a symbol, or, considering the nature of Sony and Disney/Marvel’s competing interests, a trademark.

5.

The Peter Parker of the regular Marvel Universe has no real fears in any of his battles, which he always manages to survive. He’s barely aged 10 years in the 52 since he first appeared. Immortality has erased the stakes of his existence. He has no reason to evolve. These are the kinds of story-telling decisions, made in the interest of the profit motive, that can rob a character of his soul.

The best thing about the Peter Parker of the Ultimate Universe is his mortality. He dies at the age of 16 in Ultimate Spider-Man #160 (August 2011) saving his aunt, his friends, and his neighbors from the Green Goblin. Unless something happened in between the panels that Bendis did not mention, he dies a virgin. And he does not come back. Death makes his sweetness and his goodness tragic and beautiful. It makes Peter Parker human, and, in at least one particular way, a superhero who could be you.

I don’t imagine the Spider-Man Lee and Ditko created in 1962 dying in any major battle, but I do imagine an alternate reality for him, one that diverges from the Marvel storyline sometime in the early ’70s, when Parker is still in college. He realizes at that point that he’s gone about as far as he could go as Spider-Man, which was always a fun but immature project. He learns to dislike violence and prefers helping people in more peaceful ways. He spends more time in costume at children’s hospitals, and eventually starts showing up out of costume. More superheroes have shown up in New York, and most of them, he’s now humble enough to realize, are better at crime fighting. He goes for one last night-swing, comes home to his apartment, folds up his costume and places it in a box at the back corner of his closet.

He starts dating more and notices that he has fewer inhibitions. After breaking up once with Mary Jane Watson, he starts dating a handsome man he meets in a chemistry lab. It goes on for a few months, he discovers a form of affection he didn’t realize he was capable of, but he returns happily to Mary Jane.

He graduates college. He forgoes a hard career in science after he discovers an allergy to corporate structures and a love of teaching. He teaches in one of New York’s magnet programs while at home he tinkers with his brilliant inventions, creating all sorts of wonders far more interesting than web fluid. He decides to keep his work to himself.

He marries Mary Jane and they have children. They enter into a routine by the time they hit their 40s. On Friday nights, they go up to the rooftop of their Park Slope home. Mary Jane lights up a joint. He performs some mild acrobatics. Then they go back downstairs.

The kids graduate high school. They graduate college. They get married and give him grandchildren.

And then Peter Parker, the most beautiful man New York has ever known, dies.

Image Credit: Wikipedia