Shown at this year’s Tribeca Film Festival and coming soon to a multiplex near you is a new movie called Palo Alto. It’s adapted from a book of short stories written by a member of the cast. Surely you’ve heard of the guy. There’s a sporting chance you despise him. His name is James Franco.

What’s interesting about James Franco is not that he has parlayed the job of movie star into a cottage industry of endeavors that includes short story writer, poet, novelist, memoirist, artist, teacher, movie director, Broadway star, Oscar host, fragrance pitchman, perpetual grad student, and, to hear my 25-year-old niece and her girlfriends tell it, the smokingest thing in pants. No, what’s interesting – what’s instructive – about James Franco is the way his precocity has turned him into a lightning rod, into one of those polarizing figures people either love, or love to hate.

I’ve always found such vitriol magnets irresistible. My personal pantheon includes the likes of Richard Nixon, Michael Jordan, Margaret Thatcher, Tom Cruise, Robert McNamara, and Dick Cheney – a gaggle of paranoiacs, megalomaniacs, sore winners, and evil geniuses so immaculately loathsome that they manage to flip my emotional gyroscope and become almost…lovable. Of course most people are content to hate such people, pure and simple, praying for their downfall and relishing the moment when it comes.

There’s a German word for almost everything and the German word for this icky delight people derive from the misfortune of others is schadenfreude, literally “damage joy,” or malicious gloating. To my knowledge there is no German word for the converse of schadenfreude, that is, resentment for the success of others, an emotion that’s especially prevalent in creative fields. I’ve been around enough creative types – writers and artists in New York, car stylists in Detroit, songwriters in Nashville, movie people in Los Angeles – to know that the only thing more toxic and debilitating than their schadenfreude is their seething resentment over the success of a rival. Especially when it’s seen as unearned.

You saw this same resentment go thermonuclear back in 2010 when Jonathan Franzen, another guy many people love to hate, got his unshaven face on the cover of TIME magazine. So unearned!, cried the outraged multitudes. The fury of their reaction was a telling sign of the times we live in, its toxic stew of snark and schadenfreude and resentment, all of it ready to go viral in the time it takes to hit Send. Before Franzen’s anointment, it had been a decade since a living writer had made the cover of TIME (Mark Twain did it in 2008, Stephen King in 2000). There was a time, the 1950s and ‘60s, when such appearances were virtually an annual rite (T.S. Eliot and Robert Frost did it the same year, 1950, and they were poets). These appearances were causes for widespread celebration in the literary world, not because everyone loved the writing of, say, Arthur Schlesinger Jr., but because it was a kick to see a writer enjoy a dollop of fame and increased sales. As Franzen and Franco have shown, those days are long gone. And we’re all poorer for it.

I spent my life believing I was immune to this kind of petty resentment, but recently discovered I am not. (I’m guessing no one is.) When an acquaintance of mine snagged a monster advance for his first novel, I actually sat down and did the math and figured out that his advance was exactly 400 times larger than the advance I’d just gotten for my third novel. This made me sick – not the whopping disparity in our paydays, but the very fact that I cared. It took me several days to get over the shame I felt for being so petty, and several more to come around to feeling what I should have felt all along – namely, delight for my acquaintance’s astonishing good fortune, and pride in the fact that I had sold another book. It was an unnerving emotional roller-coaster ride.

Which brings us back to James Franco. Judging by the reaction to Janet Potter’s recent essay here at The Millions, the people most likely to work up a foam-at-the-mouth hatred for Franco are aspiring writers. We’re back to the converse of schadenfreude. Potter’s essay grew out of a recent poetry reading she attended in Chicago featuring Franco and Frank Bidart, a renowned poet who has become a mentor to Franco and a vocal supporter of Franco’s literary ambitions. Franco’s first book of poetry is called Directing Herbert White, a reference to the short movie he directed that was inspired by Bidart’s poem, “Herbert White,” which is narrated by a necrophiliac murderer. At the reading, Bidart said it was “thrilling” to watch Franco turn his poem into a movie, and he praised Franco as someone who “astonishes the guardians of category.” To her surprise, Potter found that this unlikely pairing of the poet and the movie star made for an “unironically enjoyable and inspiring” evening.

Which brings us back to James Franco. Judging by the reaction to Janet Potter’s recent essay here at The Millions, the people most likely to work up a foam-at-the-mouth hatred for Franco are aspiring writers. We’re back to the converse of schadenfreude. Potter’s essay grew out of a recent poetry reading she attended in Chicago featuring Franco and Frank Bidart, a renowned poet who has become a mentor to Franco and a vocal supporter of Franco’s literary ambitions. Franco’s first book of poetry is called Directing Herbert White, a reference to the short movie he directed that was inspired by Bidart’s poem, “Herbert White,” which is narrated by a necrophiliac murderer. At the reading, Bidart said it was “thrilling” to watch Franco turn his poem into a movie, and he praised Franco as someone who “astonishes the guardians of category.” To her surprise, Potter found that this unlikely pairing of the poet and the movie star made for an “unironically enjoyable and inspiring” evening.

Her sentiment was not unanimous. Ian Belknap, who also attended the reading, wrote that Franco is a “slack and slipshod writer – a writer whose name we would never know if we did not see it on marquees and posters.” Belknap added that Franco’s writing is “farcical beat-offery,” his poetry is an “aggressive and sustained campaign of dipshit-ification,” and Franco himself is “more pretentious than the leotard-wearingest mime.”

Vitriol can be so funny! Amusing as it is, Belknap’s rant raises serious questions, such as: since this is still sort of a free country, shouldn’t someone who is successful in one field be free to dabble in another field or, in Franco’s case, many other fields? And even if Franco’s celebrity makes it easier for him to get published than a more talented nobody, is it really true that a book by a movie star automatically siphons vital money from more deserving writers? I have my doubts. Franco has said that he hopes his celebrity will bring new readers to all poetry and fiction. Maybe it will. Given the sorry state of reading in America today, I say anything that might get people to read is worth a shot.

Ian Belknap, it turns out, wrote and performed a one-man show in Chicago last year with a title that says it all: “Bring Me the Head of James Franco, That I May Prepare a Savory Goulash in the Narrow and Misshapen Pot of His Skull.” Asked by a Chicago Tribune writer to explain his beef with Franco, Belknap replied, “The basic thrust is that Franco has taken the most bloated, lightweight approach to the arts I’ve ever seen…My problem is with the people who ostensibly believe in the arts, as Franco claims he does, who then erode the value of art from within…(M)y qualm is with the access to an audience, resources, publishing and galleries by people like him.” Among “people like him” Belknap includes Ethan Hawke playing novelist and Kevin Bacon playing in a band.

Wait a minute. Nobody squawks when established writers publish shitty books, something that happens every day, to the detriment of worthy unknowns. And nobody squawked when a bunch of bestselling authors – Stephen King, Amy Tan, Dave Barry, and Barbara Kingsolver, among others – formed a band called Rock Bottom Remainders and hauled in some $2 million from their performances and recordings – money that, in theory, was diverted from the pockets of more worthy professional musicians. (It probably helped that the wealthy authors didn’t take themselves too seriously and they donated the $2 million to charity.)

But back to Palo Alto and Palo Alto and “Palo Alto” – the place that inspired the book of short stories that inspired the movie. Franco grew up in this privileged California town, and his book of short stories attempts to capture the anomie of coming of age in such a place. The writing is flat, wooden, and disjointed, not an easy combo to pull off. The movie isn’t much better – a string of vignettes about teenagers hooking up, binge drinking, barfing, smoking weed, cutting down trees, and driving the wrong way on the freeway. We’re reminded, yet again, how tough it is to be a rich teenager.

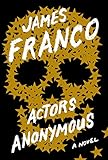

Last year, Franco followed Palo Alto with his first novel, Actors Anonymous, which includes an actor named James Franco and feels like a dashed-off first draft in need of rumination and polishing. Like his other books, it got largely negative reviews and inspired widespread foaming at the mouth.

Last year, Franco followed Palo Alto with his first novel, Actors Anonymous, which includes an actor named James Franco and feels like a dashed-off first draft in need of rumination and polishing. Like his other books, it got largely negative reviews and inspired widespread foaming at the mouth.

The self-referential streak in Franco’s writing announces that he has decided to write what he knows. Normally a hobbling strategy for a writer unless you happen to be a Proust, a Joyce, or an Updike, this might yet prove to be a smart move on Franco’s part. His intimate familiarity with the workings of celebrity puts him in touch with a potentially rich source of material, especially in a culture like ours that’s drunk on the stuff. Unfortunately, Franco has not yet figured out a way to write knowingly about what he knows. Consider the poem “Because,” which opens Directing Herbert White. It’s worth quoting in its entirety:

Because I played a knight,

And I was on a screen,

Because I made a million dollars,

Because I was handsome,

Because I had a nice car,

A bunch of girls seemed to like me.But I never met those girls,

I only heard about them.

The only people I saw were the ones who hated me,

And there were so many of those people.

It was easy to forget about the people who I heard

Like me, and shit, they were all fucking fourteen-year-olds.And I holed up in my place and read my life away,

I watched a million movies, twice,

And I didn’t understand them any better.But because I played a knight,

Because I was handsome,This was the life I made for myself.

Years later, I decided to look at what I had made,

And I watched myself in all the old movies, and I hated that guy I saw.But he’s the one who stayed after I died.

After bumbling along on the surface of some mildly interesting ideas, the poem suddenly dives deep and says something visceral and revealing: I watched myself in all the old movies, and I hated that guy I saw. Now we’re getting somewhere dark and promising – the movie star’s dirty little secret, his loathing for that chimera on the screen who millions of people worship. Maybe, with time, Franco will grow into the role of Hollywood mole, delivering wise dispatches from inside the belly of the beast, à la Bruce Wagner or Joan Didion or Nathanael West.

I’m not going to wait and see, and I’m not going to waste my time hoping James Franco fails because I know this: schadenfreude and its evil doppelgänger, resentment, are a pair of stone-cold killers. They will kill you and they will kill your writing. So you might want to do what I’m going to do: I’m going to forget about James Franco and Jonathan Franzen and other writers’ advances, then get on with my own work.