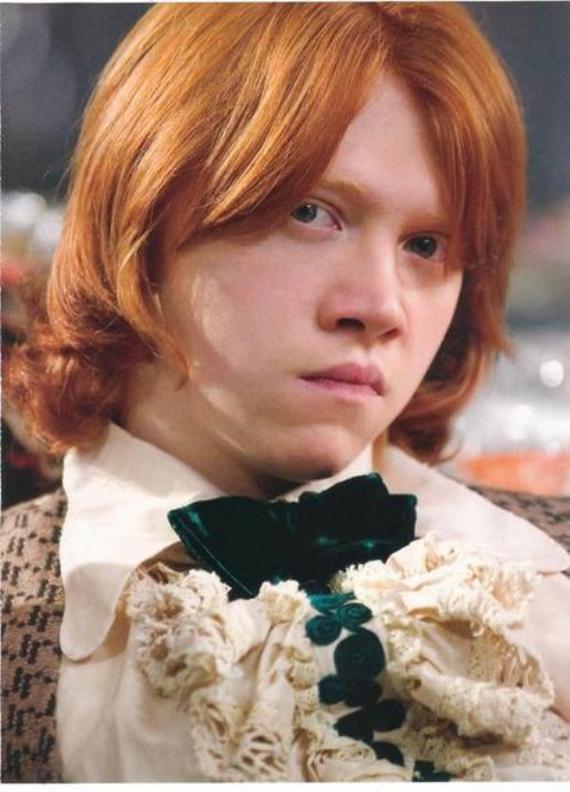

Recently J.K. Rowling dropped a bombshell on the smoking remnants of one of the fiercest shipping wars of the last decade: “I wrote the Hermione/Ron relationship as a form of wish fulfillment. That’s how it was conceived, really. For reasons that have very little to do with literature and far more to do with me clinging to the plot as I first imagined it, Hermione ended up with Ron.” It’s from an interview conducted by Hermione herself, Emma Watson, excerpted in the Sunday Times; the full article, in an issue of Wonderland Magazine guest-edited by Watson, came out on Friday. (The words “publicity stunt” may be floating around, but that kind of speculation is useless.) The ladies, bafflingly, “agree[d] that Harry and Hermione were a better match than Ron and Hermione,” Ron wouldn’t be able to satisfy Hermione’s needs, and the pair as she wrote them would need relationship counseling. And then the internet exploded.

OK, first of all, JKR, please just stop. Is the most aggravating thing about all of this the fact that Hermione doesn’t belong with either of these jokers? Was there literally anyone else for her to get with? (Rowling’s shoddy math suggests possibly not; despite the insistence in an early interview that “there are about a thousand students at Hogwarts,” there remain just eight Gryffindors in the matriculating class of ’98, suggesting no more than three dozen in the entire year, a whole house of which remain irredeemably, mustache-twirlingly evil despite seven books in which to write convincing moral ambivalence and complexity. But I digress.)

But also, JKR, please just stop — for reasons that have a lot to do with literature. Because the weirdest thing about the statement is the “wish fulfillment” bit, which I’ve seen interpreted many different ways, none of them satisfactory. My read of it is accompanied by this question: how is a writer setting down a plot from her head wish fulfillment? Forced, sure — this certainly wasn’t the only instance where it seemed that Rowling was stifled by the tyranny of the outline she mapped out more than a decade before penning The Deathly Hallows. (I spent years wondering how the hell the final word would, as promised, be “scar,” though by the time I got to the last page of the epilogue I was too infuriated to care.)

But also, JKR, please just stop — for reasons that have a lot to do with literature. Because the weirdest thing about the statement is the “wish fulfillment” bit, which I’ve seen interpreted many different ways, none of them satisfactory. My read of it is accompanied by this question: how is a writer setting down a plot from her head wish fulfillment? Forced, sure — this certainly wasn’t the only instance where it seemed that Rowling was stifled by the tyranny of the outline she mapped out more than a decade before penning The Deathly Hallows. (I spent years wondering how the hell the final word would, as promised, be “scar,” though by the time I got to the last page of the epilogue I was too infuriated to care.)

This isn’t the first time that Rowling has “revealed” further details about her characters, as if she is their publicist rather than their creator. The Dumbledore announcement was, admittedly, totally awesome, for the political ramifications at the very least. But Rowling seems insistent on undercutting her authorial intent, or her position as omniscient narrator, the sort of “I would have loved for this to happen” statement, it’s like, really? I was under the impression that you were making all the things happen. (The full article in Wonderland—or the full interview, excerpted at Mugglenet — is worth a read for its continued, almost amplified strangeness — Rowling speaks of being shocked to see the filmmakers depicting things she hadn’t written but was feeling about the characters, like the scene between Harry and Hermione in the tent in the first installment of The Deathly Hallows. “Yes, but David and Steve — they felt what I felt when writing it,” Rowling tells Watson, referring to the director and screenwriter. “That is so strange,” Watson responds. Yes — this whole thing is so strange. It feels like there’s a simultaneous disregard for the concept of subtext and the idea that the characters were driven by something other than Rowling’s own fingers. “JKR, I think, probably is still in mystical mode when talking about her characters and work,” Connor Joel said to me in a Twitter conversation. “Which can be OK…sometimes.”)

Is a writer allowed to have regrets? Certainly. Is she allowed to air them publicly? I mean, yeah, it’s a free internet, why not? Do I want to hear a single additional word about the world of Harry Potter from J. K. Rowling that is not in the form of another book? Unless she is going to travel via Time-Turner to the past and personally validate all of my ships, no, not particularly — though that’s just me. (On second thought, no, not even that: sometimes the joy of delving into subtext is that it remains, well, sub.) The night all this came out (my new BFF) Anne Jamison kicked off a round of hilarious authorial regrets on Twitter, collected here. (For example: “‘I realize I made generations believe instant antipathy is a valid basis for ideal marriage,’ sighed Ms Austen, ‘I just thought he was hot.’”)

All joking aside, these tweets got me thinking: how often has this sort of thing happened in the past? Is there something fundamental in the author/reader relationship that feels like it’s being abused in Rowling’s admissions — or is she just following a long tradition of regretful writers undermining their own authority via statements after publication? Initial research suggests that some of the most famous writers haven’t stayed as faithful to their own original texts as I might have guessed. I mean, these examples aren’t exactly the same (I can hear you saying this, even now!), and that might get at what feels so incredibly strange about the “wish fulfillment” idea that Rowling’s putting forth. But regrets are regrets, and once the pages are printed — and even with all the revisions and retractions in the world — there’s essentially no going back. Here are five authors who had a variety of regrets and later said they really wished they’d done things differently — and, in many cases, went on to try to actually do things differently, to varying degrees of success:

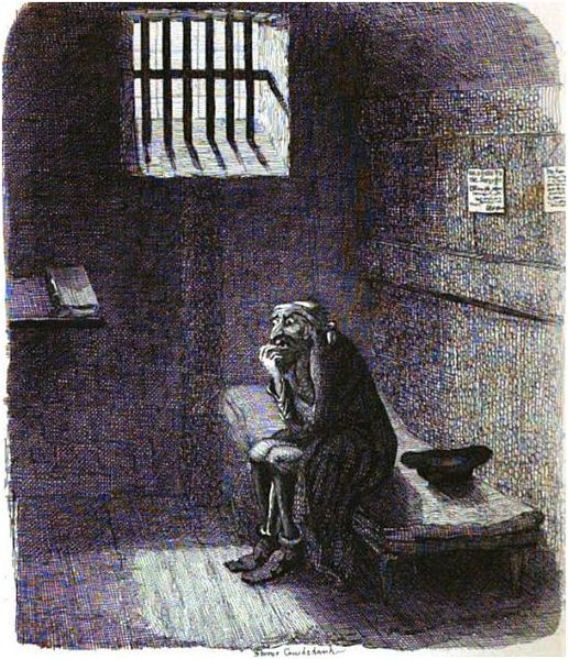

Charles Dickens

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Oliver Twist’s greedy, villainous employer, Fagin, is most famously marked by his Jewishness, via every derogatory stereotype in the history of man and by outright assertion: references as “the Jew” outnumber “the old man” in the original text nearly ten-to-one. There was no doubt in Dickens’s mind, nor that of many of his mid-Victorian counterparts, that this was totally fine, that Fagin’s crimes fell right in line with his background: he stated later, by way of (really poor and blatantly anti-Semitic) defense, that “that class of criminal almost invariably was a Jew.” But in 1860 Dickens sold his house to a Jewish couple and befriended the wife, Eliza, who wrote him later to say that the creation of Fagin was a “great wrong” to the Jewish people. Dickens saw the light, albeit in a sort of, “Well, some of my best friends are Jewish!” sort of way, and began stripping out references to Fagin’s religion from the text, as well as the caricature-like aspects: at a reading of a later version, it was observed that, “There is no nasal intonation; a bent back but no shoulder-shrug: the conventional attributes are omitted.” But was it too little too late? After all, the original depiction of Fagin has endured through the centuries. Dickens tried, anyway. “There is nothing but good will left between me and a People for whom I have a real regard,” he wrote. “And to whom I would not willfully have given an offence.”

Oliver Twist’s greedy, villainous employer, Fagin, is most famously marked by his Jewishness, via every derogatory stereotype in the history of man and by outright assertion: references as “the Jew” outnumber “the old man” in the original text nearly ten-to-one. There was no doubt in Dickens’s mind, nor that of many of his mid-Victorian counterparts, that this was totally fine, that Fagin’s crimes fell right in line with his background: he stated later, by way of (really poor and blatantly anti-Semitic) defense, that “that class of criminal almost invariably was a Jew.” But in 1860 Dickens sold his house to a Jewish couple and befriended the wife, Eliza, who wrote him later to say that the creation of Fagin was a “great wrong” to the Jewish people. Dickens saw the light, albeit in a sort of, “Well, some of my best friends are Jewish!” sort of way, and began stripping out references to Fagin’s religion from the text, as well as the caricature-like aspects: at a reading of a later version, it was observed that, “There is no nasal intonation; a bent back but no shoulder-shrug: the conventional attributes are omitted.” But was it too little too late? After all, the original depiction of Fagin has endured through the centuries. Dickens tried, anyway. “There is nothing but good will left between me and a People for whom I have a real regard,” he wrote. “And to whom I would not willfully have given an offence.”

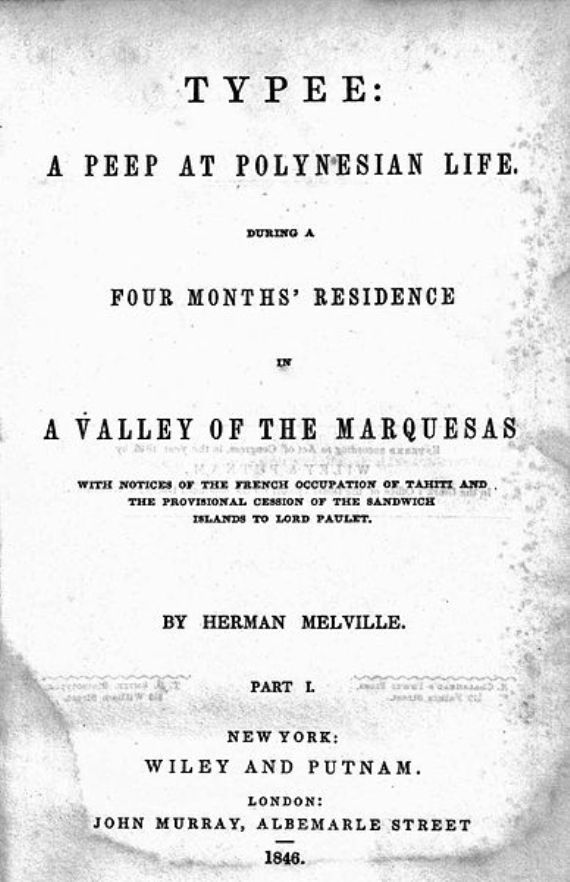

Herman Melville

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Typee, Melville’s first novel and the most popular during his lifetime, is described as “one of American culture’s more startling instances of a fluid text.” There appears to be no definitive version of Typee — the sort of book that makes you question just how definitive anything you read really is. “All texts are fluid,” writes John Bryant, a scholar who’s done extensive work on Typee, examining its states of flux. “They only appear to be stable because the accidents of human action, time and economy have conspired to freeze the energy they represent into fixed packets of language.” Some of the changes — which were made over the course of half a century, from the first drafts Melville penned fresh off the high seas to the final years of his life — came from pressures from critics and his publishers: disparagement of missionary culture, expanded upon in first drafts, was largely removed in subsequent editions. Some requests for changes, including a toning down of the ‘bawdiness’ of earlier editions, took place decades later, when Melville was an old man — “Certain passages were to be restored, a paragraph on seaman debauchery dropped, and ‘Buggery Island’ changed to ‘Desolation Island,’” writes Bryant, though not all of these changes were honored in the posthumous edition. Bryant has developed a digital edition to view the fluid text as a whole, though perhaps even that can’t — and shouldn’t — answer the question of whether one version or another can be called the definitive text.

Typee, Melville’s first novel and the most popular during his lifetime, is described as “one of American culture’s more startling instances of a fluid text.” There appears to be no definitive version of Typee — the sort of book that makes you question just how definitive anything you read really is. “All texts are fluid,” writes John Bryant, a scholar who’s done extensive work on Typee, examining its states of flux. “They only appear to be stable because the accidents of human action, time and economy have conspired to freeze the energy they represent into fixed packets of language.” Some of the changes — which were made over the course of half a century, from the first drafts Melville penned fresh off the high seas to the final years of his life — came from pressures from critics and his publishers: disparagement of missionary culture, expanded upon in first drafts, was largely removed in subsequent editions. Some requests for changes, including a toning down of the ‘bawdiness’ of earlier editions, took place decades later, when Melville was an old man — “Certain passages were to be restored, a paragraph on seaman debauchery dropped, and ‘Buggery Island’ changed to ‘Desolation Island,’” writes Bryant, though not all of these changes were honored in the posthumous edition. Bryant has developed a digital edition to view the fluid text as a whole, though perhaps even that can’t — and shouldn’t — answer the question of whether one version or another can be called the definitive text.

F. Scott Fitzgerald

Image via Wikimedia Commons

F. Scott Fitzgerald, a man prone to last-minute editorial regrets: he sent a telegram to his publisher as The Great Gatsby was going to press, asking to change the title to Under the Red, White, and Blue. It arrived too late. He’d wavered so much on the title already — amongst a dozen other suggestions, he’d been set on Trimalchio in West Egg for a good while. But Tender is the Night suffered, in his opinion, from problems far larger than what was printed on the dust jacket. It was published in 1934 to poor critical and public response, and Fitzgerald set to work figuring out why it didn’t work. When it was reprinted two years later, he wanted to make minor changes and clarifications, and wrote that, “sometimes by a single word change one can throw a new emphasis or give a new value to the exact same scene or setting.” But he soon decided it wasn’t a “single word” — it was the entire structure: “If pages 151-212 were taken from their present place and put at the start,” he wrote to his editor at Scribner, “the improvement in appeal would be enormous.” He set to work slicing apart the novel — physically — and rearranging it in the order he felt it was now meant to be, the narrative now chronological rather than reliant on flashback. The copy is on display at Princeton, with Fitzgerald’s penciled note written inside the front cover: “This is the final version of the book as I would like it.” After Fitzgerald’s death, Malcolm Cowley decided to try to fulfill these editorial wishes, rearranging the book based on the notes and cut-up version. But people weren’t any more interested in this version than the first, and in the intervening half-century, the original has endured.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, a man prone to last-minute editorial regrets: he sent a telegram to his publisher as The Great Gatsby was going to press, asking to change the title to Under the Red, White, and Blue. It arrived too late. He’d wavered so much on the title already — amongst a dozen other suggestions, he’d been set on Trimalchio in West Egg for a good while. But Tender is the Night suffered, in his opinion, from problems far larger than what was printed on the dust jacket. It was published in 1934 to poor critical and public response, and Fitzgerald set to work figuring out why it didn’t work. When it was reprinted two years later, he wanted to make minor changes and clarifications, and wrote that, “sometimes by a single word change one can throw a new emphasis or give a new value to the exact same scene or setting.” But he soon decided it wasn’t a “single word” — it was the entire structure: “If pages 151-212 were taken from their present place and put at the start,” he wrote to his editor at Scribner, “the improvement in appeal would be enormous.” He set to work slicing apart the novel — physically — and rearranging it in the order he felt it was now meant to be, the narrative now chronological rather than reliant on flashback. The copy is on display at Princeton, with Fitzgerald’s penciled note written inside the front cover: “This is the final version of the book as I would like it.” After Fitzgerald’s death, Malcolm Cowley decided to try to fulfill these editorial wishes, rearranging the book based on the notes and cut-up version. But people weren’t any more interested in this version than the first, and in the intervening half-century, the original has endured.

Ray Bradbury

Image via Wikimedia Commons

If the biggest disappointment of 2015 will be the fact that almost nothing resembles the 2015 bits of “Back to the Future” (what’s sadder — no hoverboards or no magical pizzas?), it speaks to the risks of setting a sci-fi novel in the not-so-distant future. When Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles, first published in 1947, were reissued fifty years later, the stories’ chronological start date was just two years away. Bradbury and his publisher made the call to bump up the timeline by three decades, 2030-2057, and made some additional editorial changes while they were at it. The timeline shift isn’t unique in science fiction: Wikipedia’s got a poetically-titled “List of stories set in a future now past,” which reveals that Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep also got a thirty-year bump. It’s an interesting question, and one that may crop up more and more as time goes on: does reading about some sort of alien “future” that’s now a few years in the past take a reader right out of the story? Isn’t there some joy in imagining Bradbury imagining 1999 in 1947, a vision of the future from that precise point in the past?

If the biggest disappointment of 2015 will be the fact that almost nothing resembles the 2015 bits of “Back to the Future” (what’s sadder — no hoverboards or no magical pizzas?), it speaks to the risks of setting a sci-fi novel in the not-so-distant future. When Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles, first published in 1947, were reissued fifty years later, the stories’ chronological start date was just two years away. Bradbury and his publisher made the call to bump up the timeline by three decades, 2030-2057, and made some additional editorial changes while they were at it. The timeline shift isn’t unique in science fiction: Wikipedia’s got a poetically-titled “List of stories set in a future now past,” which reveals that Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep also got a thirty-year bump. It’s an interesting question, and one that may crop up more and more as time goes on: does reading about some sort of alien “future” that’s now a few years in the past take a reader right out of the story? Isn’t there some joy in imagining Bradbury imagining 1999 in 1947, a vision of the future from that precise point in the past?

Anthony Burgess

Image via erokism/Flickr

And then what to do if an author wishes the entire book had never been written? One famous example: “J.D. Salinger spent 10 years writing The Catcher in the Rye and the rest of his life regretting it,” Shane Salerno and David Shields assert in their recent biography. But Salinger’s dissatisfaction appeared to stem from the extraordinary amount of unwanted attention he received for it over the years. But what about Anthony Burgess, who wrote about A Clockwork Orange in his Flame into Being: The Life and Work of D. H. Lawrence, published in 1985:

And then what to do if an author wishes the entire book had never been written? One famous example: “J.D. Salinger spent 10 years writing The Catcher in the Rye and the rest of his life regretting it,” Shane Salerno and David Shields assert in their recent biography. But Salinger’s dissatisfaction appeared to stem from the extraordinary amount of unwanted attention he received for it over the years. But what about Anthony Burgess, who wrote about A Clockwork Orange in his Flame into Being: The Life and Work of D. H. Lawrence, published in 1985:

We all suffer from the popular desire to make the known notorious. The book I am best known for, or only known for, is a novel I am prepared to repudiate: written a quarter of a century ago, a jeu d’esprit knocked off for money in three weeks, it became known as the raw material for a film which seemed to glorify sex and violence. The film made it easy for readers of the book to misunderstand what it was about, and the misunderstanding will pursue me until I die. I should not have written the book because of this danger of misinterpretation, and the same may be said of Lawrence and Lady Chatterley’s Lover.

Lawrence died decades before the obscenity trials placed his book at the center of the moral questions of literature and society. Burgess had decades to witness the unraveling of the “misunderstandings” of the novel he will always be most remembered for. As for its merits as a work of literature? He also described it as “too didactic to be artistic.” Ah, well. Everyone is entitled to their opinions of a book and its characters. Even, I suppose, the author himself.