1.

“What does your tattoo say?” Lorrie Moore asks our young waiter.

“What does your tattoo say?” Lorrie Moore asks our young waiter.

Moore has the distinct quality of seeming silent even when she is speaking. Her low, honeyed voice moves in jovial swoops, and when she laughs, she does so deeply, like she means it. We sit tucked away in a corner of Brassiere V, on Madison’s trendy Monroe Street, Moore sipping on beer and coffee like she has a hundred times before for a hundred other journalists and I imagining an invisible web spreading out from her, potential narratives vibrating on the periphery.

“It says ‘I am the rock that grounds me.’ Deep,” he adds, sort of apologetically.

“That’s too deep for a tattoo,” Moore teases. Turning back to me, she says, “There was a girl who used to bartend here with a tattoo I borrowed for a character. It was a city on her neck and I had a character who had all the cities that she didn’t want to go back to as tattoos.” KC, a young but tired indie musician, is tattooed with “Decatur,” “Moline,” and “Swanee” and befriends, at her apathetic boyfriend’s suggestion (and with questionable motives) an aging and maybe-horny man.

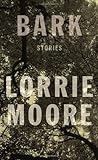

The story in which KC appears, “Wings,” was published in Harper’s and is in Moore’s new collection, Bark. “Wings” is both a summation and forgiveness of the gross things we do, like dating schmucky people and schmoozing the nice-but-wealthy old man next door, things meant to help us get ahead but that instead leave us a little behind. “Ignorance ironically arranged for future self-knowledge,” thinks KC, “Life is never perfect.”

The story in which KC appears, “Wings,” was published in Harper’s and is in Moore’s new collection, Bark. “Wings” is both a summation and forgiveness of the gross things we do, like dating schmucky people and schmoozing the nice-but-wealthy old man next door, things meant to help us get ahead but that instead leave us a little behind. “Ignorance ironically arranged for future self-knowledge,” thinks KC, “Life is never perfect.”

Taking in the room, Moore explains that her writing usually starts with characters and predicaments, “people who are up against the world in a particular manner. Feelings you are trying to get at with language.”

Thirty-seven years have passed since Moore’s first published work appeared, a short story about a janitor in an elementary school, which won Seventeen magazine’s fiction contest in 1976. She was 19 years old and refers to the experience as a “fluke,” noting that she didn’t get serious about writing until many years later. Originally, she had hoped to win Seventeen’s art contest but says that by time she wrested up the courage to send them anything at all, she was writing stories. “What I remember most is the 500 dollars,” she recalls. “Which seemed a fortune to me, and I was able to buy my textbooks plus a new stereo.” Her next published work would not appear until 10 years later, the barbed and reflexive Self-Help, a book that hooks you with all the tough, but good-natured love readers go back for again and again.

Born in Glens Falls, a small town in upstate New York, Moore attended Saint Lawrence University where she studied English, graduating summa cum laude. Her father was educated as a scientist and worked in insurance, though his true love was music, while her mother was a nurse, a teacher and homemaker, and a “community activist of sorts.” The household was fairly religious; dinners began with grace and there was minimal TV watching, a home replete with all the “general suspicions of the 20th century” Moore said last October in a talk, “Watching Television.” Like many of her generation, her and her brother’s salad days were full of illicit television viewing in the basement TV room and mad dashes back upstairs as their parents pulled into the driveway. Their mother would sometimes press her hand against the TV screen to see if it was warm, the vestiges of “Gilligan’s Island” and “F-Troop” evaporating off the glass.

Moore says her parents weren’t supportive or unsupportive of her writing career. “No parent in their right mind should really encourage a child to become a writer. It has to come completely from the child,” she explains. Besides the relative poverty most writers at some point find themselves in, the writing life also tends to be an isolated one, with observational skills sharpening at a quicker pace than social ones. I ask her whether or not she feels her capacity to observe ever gets in the way of simply interacting with people. “I think with all observers it’s a problem,” she remarks, and refers to one of her favorite writers, Alice Munro. “I can’t remember precisely what she said,” Moore says of Munro’s acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize in Literature, “But I think essentially it was ‘I just want to be normal now.’” It’s the old idea that to be a writer is to lead a double life. “You’re not doing quite what other people are doing in the same situation perhaps,” Moore reflects.

Part of what defines Moore’s public persona is the debate over how autobiographical the work is, as well as the fervid enthusiasm of her fans. Set in that comfortably crummy place we call middle class, Middle America, her protagonists are often witty, stubborn, and charmingly self-deprecating, a humor mostly lost on the mollifying Midwesterners that surround them. It’s an embarrassing show of intelligence that leaves them feeling more isolated and misunderstood than before. Moore invokes with eerie familiarity awkward moments that tend not to pan out so well — if at all — in a landscape distinctly red, white, and blue. Her hometowns are dead-on, though they have caught her some flack from a few of her Midwestern neighbors. “She made it clear in many interviews how little she thought of the city and its people,” an anonymous reader writes on Madison’s local The Daily Page. “This disdain also showed up in her fiction.”

Home of the University of Wisconsin Badgers and the fiercely granola, Madison is somewhat of an anomaly: a university-town hailed for its liberalism and farmers’ markets in a largely conservative state. The summers in Madison are buggy and bird-chirpy, full of Friday night fish fries and beer-drinking Lutherans. The winters are insanely cold, with hoar frost and black ice and gobs of snow. Cars remain salt-encrusted until mid-March, when temperatures rise high enough to wash them without the doors freezing shut. Wisconsin, like the rest of the Midwest, is dull and cozy and more appealing when filtered through fiction or Instagram.

Some locals took umbrage with Moore’s story that appeared in 1997, in The New Yorker. “People Like That Are the Only People Here,” is a tale in which a baby is diagnosed with cancer and undergoes an operation with some procedural errors. Moore has a son of college-age who was also very ill as a baby and Moore, speaking to the Guardian, explains that the story was assumed by some to be attack on the local hospital. “They felt that I was hard on the medical students, and hard on the doctors.”

From the opening paragraph, it is hard to divorce the fiction from its foundation in reality.

The Surgeon says the Baby has a Wilms’ tumor. The Mother, a writer and teacher, asks, “Is that apostrophe ‘s’ or ‘s’ apostrophe?” The doctor says the Baby will have a radical nephrectomy and then chemotherapy. The Mother begins to cry: “Life has been taken and broken, quickly, like a stick.” She thinks perhaps she is being punished for her errors as a mother. At home, she leaves a message for the Husband. The Baby has a new habit of waving goodbye to everything, which breaks her heart. She sings him to sleep and says, “If you go, we are going with you.” The Husband comes home and cries. He tells the Mother, “Take notes. We are going to need the money.” He says, “I can’t believe this is happening to our little boy,” and cries again. The Mother tries to bargain for the Baby’s life, imagining the higher power she addresses as the Manager at Marshall Field’s. She argues with her husband over the idea of selling the story: “This is a nightmare of narrative slop.”

Others closer to Moore have also questioned whether or not they’ve made it into her work. “People get confused. People get paranoid,” she says, telling the story of a man she once dated who became suspicious of a specific character. “First of all, the character is a woman,” she remembers saying to him, “Second of all, darling, the character has a job.”

She ruffles slightly when asked directly how autobiographical the work is, and is careful to describe writing like stagecraft. “I’m never writing about myself. It’s [about] observing a feeling in someone else. Imagining a feeling in a particular character — and that character is a collage from your mind — and then you enter into that character like an actor or actress. You’re not going to be journaling. You’re trying to find, as efficiently as possible, a thing that person would say — or possibly say — and definitely do, that you, the author, are interested in the reader feeling. All of that happens at your desk.”

Moore does not journal at all, but she does keep a notebook. “One should always take notes and try not to be lazy about it,” she says. And to that end, one is reminded of Joan Didion, who failed at keeping a diary, instead finding comfort in the distinction of note taking. “The point of my keeping a notebook has never been, nor is it now, to have an accurate factual record of what I have been doing or thinking,” Didion writes in her essay “On Keeping a Notebook.” “That would be a different impulse entirely, an instinct for reality which I sometimes envy but do not possess.” Similarly, Moore’s work is brimming with a brilliant discernment of what may be interesting to express through prose as opposed to what is overly expressive, a literary refining process Didion describes as “just this side of self-effacing.”

“People Like That” is one of Moore’s best-loved short stories, and to say it is simply memoir perhaps diminishes her ability to pull back and allow the reader some breathing room, a little space for Moore’s audience to enter into her characters and share their pain and the evolution of their love.

Moore is no memoirist, but it is not impossible to connect a few dots between her world and that of her characters, especially when sitting in her web. A small sympathy went out to our waiter when he described the quinoa salad as a “mélange.”

“That’s a terrible word to use for food,” Moore teased. The boy blushed and fumbled for a better description. In her novel, A Gate at the Stairs, protagonist Tassie Keltjin marvels at the evolution of menu-language. “I went back to studying the menu — was it not a kind of poetry?” narrates Tassie. “There were astonishing things: crab mousseline with a shellfish cappuccino. There were fennel-cured salmon noisettes with a champagne foam. Not a Chubby Mary in the house. There was bison carpaccio with wilted spring leaves…There were salads of lambs quarters and mint and sorrel with beets and pea shoots and tomatoes that were heirloom, like brooches, and cheeses that had won prizes in shows, like dogs.”

“That’s a terrible word to use for food,” Moore teased. The boy blushed and fumbled for a better description. In her novel, A Gate at the Stairs, protagonist Tassie Keltjin marvels at the evolution of menu-language. “I went back to studying the menu — was it not a kind of poetry?” narrates Tassie. “There were astonishing things: crab mousseline with a shellfish cappuccino. There were fennel-cured salmon noisettes with a champagne foam. Not a Chubby Mary in the house. There was bison carpaccio with wilted spring leaves…There were salads of lambs quarters and mint and sorrel with beets and pea shoots and tomatoes that were heirloom, like brooches, and cheeses that had won prizes in shows, like dogs.”

Obvious correlations like tattoos and menus, or the doll hospital near Moore’s hometown and the one that appears in “Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?” are peppered throughout her prose, making it especially hard for people — fans, relatives, friends, and boyfriends — to not become paranoid. “But that’s what artists do,” Moore says, explaining that if she does borrow something like a tattoo, she asks. “And ultimately, elements of a story collide and create a certain feeling,” she says. “You are trying to give the reader an experience.” And with Moore, it’s an experience that occasionally makes the reader want to bash their head in.

“I remember reading a story of hers about a woman who drops a baby,” says Jad Abumrad, host of the popular radio show Radiolab, “and I was devastated.” The last in her collection of short stories, Birds of America, published in 1998, “Terrific Mother” opens with a young woman, Adrienne, awkward and discomfited by the idea of motherhood. At a backyard party, Adrienne is asked to hold a friend’s baby and in an unfortunate moment of picnic benches and gravity, drops and kills the child. It’s a dazzling and trenchant look at one woman’s struggle to somehow continue a life after a god-awful event; about how heavy past events can weigh in the present. “She goes right for the jugular,” says Abumrad.

“I remember reading a story of hers about a woman who drops a baby,” says Jad Abumrad, host of the popular radio show Radiolab, “and I was devastated.” The last in her collection of short stories, Birds of America, published in 1998, “Terrific Mother” opens with a young woman, Adrienne, awkward and discomfited by the idea of motherhood. At a backyard party, Adrienne is asked to hold a friend’s baby and in an unfortunate moment of picnic benches and gravity, drops and kills the child. It’s a dazzling and trenchant look at one woman’s struggle to somehow continue a life after a god-awful event; about how heavy past events can weigh in the present. “She goes right for the jugular,” says Abumrad.

Her newest collection, Bark, is perhaps her darkest yet and took her over ten years to compose. “One wants a story to be searing and to be whole in terms of what it’s taking in of the world and of life,” she writes later in an email, recognizing the punch she can pack. She suggests that the stories can stand alone, that they should perhaps be read that way. “I think as with all story collections the reader must pace herself, since certainly the writer did.”

Our waiter returns with a small pot of coffee and instructs Moore to “wait three minutes” before pouring. Turning his attention to the newly arrived couple seated next to us he recites the specials, this time without using the word “mélange.”

2.

Like many writers, Moore’s life is not innately interesting, and could be a stand in for most artistic types whose repertoire includes graduating with a liberal arts degree and moving to New York City. “I used to be skinny and young in New York,” she says laughing. Moore worked briefly as a paralegal in the city but the allure of a MFA program, especially one that would pay your tuition, proved magnetic enough to draw her away from city life. “It’s a lonely business, writing. To be around other writers — for them to read your work — it sounded like a dream come true. [And] it kind of was.” She wasn’t keen on leaving New York City but Cornell offered her the best deal. “’My god!’ I thought, ‘I’ll never see another bagel again!’ But of course the main street of Ithaca is all bagel shops.”

Shortly thereafter Moore left for a job at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, where she taught for over 30 years, only this January relocating to Vanderbilt University in Nashville. Her more recent emails are flavored slightly with southern vernacular, trying on colloquialisms like “darlin’” for size.

What is remarkable about Moore’s prose is how true it feels, her gift in pointing out the “general absurdities of being human,” as Brooke Watkins, a librarian at the New York Public Library wrote to me. I met Watkins at “Watching Television,” part of the NYPL’s annual Robert B. Silvers lectures. Her readings are a veritable bonding experience, excited conversations of “first times” with Moore’s work edge into something akin to sexual frenzy. A young man behind the merchandise table selling Moore’s work raved with abandon about “Who Will Run the Frog Hospital?” — his personal favorite — while the woman behind me avidly agreed, saying the book “enters into your bloodstream.” The two hit it off so well I felt like the third-wheel, and slouched off with my then still unread copy. (It is now also my personal favorite. Followed closely by Birds.)

Her fans have been described by the New York Times as “ardent, even cultish.” And like the equally ardent and cultish readers of Joan Didion or David Foster Wallace, writers also distinctive and evocative and deadly funny or deadly sad, we the willfully misunderstood finally feel understood, and we crave her writing, almost narcissistically so. Because we each feel like she “gets us,” we also feel — covetously and alone — that we “get her.”

It is her heroines, specifically, that cull strong, sororal ties. “I’ve met lots of men who love and admire her fiction,” writes Watkins, “but I think it’s her female readership that has more of an obsessive relationship to her work.” Moore, the writer of anxious women with rogue emotions — women unsure of what scares them most, domestic failure or domestic success — has been collectively appointed mother to a thousand disoriented daughters. “Her characters aspire toward a life of the mind,” Watkins writes. “They crave some kind of hard-won wisdom but often slip into self-deprecation and cynicism instead, which ends up being really funny.” With honed bullshit detectors and an over-developed sense of humor, Moore’s characters exemplify a “way to be resilient even when they’re sinking fast. I’ve always found her writing obliquely instructive in this way.”

Moore is no minor authority on human understanding and her language is quick, the kind of language that asks us who you are and what you want to be, reminding us that higher understanding always prevails at our own expense and that happiness can be hard work. In “How to Become a Writer Or, Have You Earned This Cliché?” Moore writes, “First, try to be something, anything else.” And then, later, “You spend too much time slouched and demoralized. Your boyfriend suggests bicycling. Your roommate suggests a new boyfriend.” And later yet:

Vacuum. Chew cough drops. Keep a folder full of fragments.

An eyelid darkening sideways.

World as conspiracy.

Possible plot? A woman gets on a bus.

Suppose you threw a love affair and nobody came.

The essay is Watkin’s personal favorite. “I’d never read anything like it,” she says. “In the end, of course, the story is a cautionary tale about a woman who sacrifices everything for the time to write, and eventually she’s left with no ideas or inspiration, or really any friends, and when I was eighteen I thought this was both sad and hilarious, and the truest thing I’d ever read.”

Exploring the demands of a life is the heart of Moore’s work, and the resonate truth of her prose has fueled a fevered desire for her books. Her characters don’t so much adventure through life as they do drift and stumble through it, making it a map of emotional landmarks, places you keep finding yourself in. One suspects that Moore is not simply writing a life, but cleverly recording yours. There is a commonality linking reader with character, an elastic boundary between her fiction and our reality that both reinforces and subverts one’s own sense of uniqueness. Coming away from one of her stories, one is reminded that we are all just doing this the best we know how.

Image via Bill Morris