At the beginning of each semester, I gather basic information from my fiction writing students such as major, hometown, and favorite book. Some of this arrives from the registrar before the semester begins, but the information isn’t always accurate, and many students accustomed to large, impersonal classes appreciate even perfunctory interest in their lives. My students’ majors are varied, and the students come from all over the world, even at a state university. With few exceptions, their book selections are depressing.

The selections are not depressing because the books are sad. That would be great. I mean depressing as in uninspired, as in the last book the students can remember reading in high school, the book a movie was based on (sometimes they have only seen the movie), the Twilight series or Hunger Games series. Pretty much any series. This semester three students picked Lord of the Flies and three picked Harry Potter, edging “no response” as the most popular titles. It’s not that these books are necessarily bad, though some are. Instead, it’s what these choices suggest to me, that books occupy an ancillary role in the students’ lives. Books are something they had to read in class, or something a movie is based on, a movie everyone else is seeing. The book is rarely the thing the student willingly came to first.

The selections are not depressing because the books are sad. That would be great. I mean depressing as in uninspired, as in the last book the students can remember reading in high school, the book a movie was based on (sometimes they have only seen the movie), the Twilight series or Hunger Games series. Pretty much any series. This semester three students picked Lord of the Flies and three picked Harry Potter, edging “no response” as the most popular titles. It’s not that these books are necessarily bad, though some are. Instead, it’s what these choices suggest to me, that books occupy an ancillary role in the students’ lives. Books are something they had to read in class, or something a movie is based on, a movie everyone else is seeing. The book is rarely the thing the student willingly came to first.

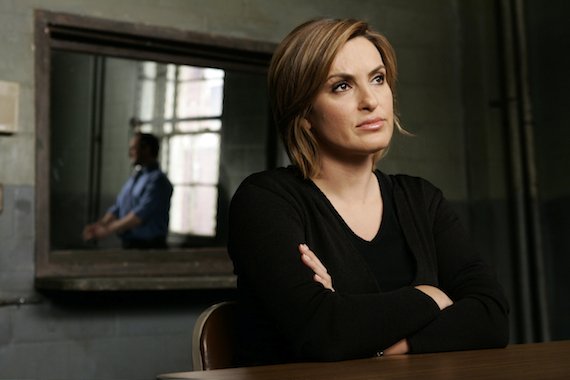

Although my students and I infrequently read the same books, we watch some of the same television shows. We’re more likely to find common ground discussing Breaking Bad than Yiyun Li. If I watched Game of Thrones or The Walking Dead, we’d have a lot to talk about because those programs influence their writing more than any author, living or dead. Other influences: CSI (in its various locales), Law and Order (in its various incarnations), True Blood (vampire everything). I’m not trying to be glib or cute. These are the narratives that influence students’ writing. It’s something I need to take seriously.

Although my students and I infrequently read the same books, we watch some of the same television shows. We’re more likely to find common ground discussing Breaking Bad than Yiyun Li. If I watched Game of Thrones or The Walking Dead, we’d have a lot to talk about because those programs influence their writing more than any author, living or dead. Other influences: CSI (in its various locales), Law and Order (in its various incarnations), True Blood (vampire everything). I’m not trying to be glib or cute. These are the narratives that influence students’ writing. It’s something I need to take seriously.

Who am I to determine what’s good or bad? That’s a reasonable question. Isn’t it my job, as possibly the only creative writing instructor these students will ever have, to place moving stories into their hands, instill the virtues of reading, caution them against the culture’s basest offerings? Yes, gladly. But that’s not the question I find myself asking. The question isn’t even how to teach writing to students who don’t read. The question is how to teach writing to students who watch movies and television instead of reading.

This class, I should note, is an upper-level elective. All of my students arrive voluntarily, and most are upperclassmen. My classes are unfailingly populated with curious young men and women. They’re earnest and respectful and hard-working. I genuinely like them. Every fall and spring there is a waitlist because students want to write stories. What they don’t particularly want to do is read them. Reading literary fiction for the pleasure or edification of reading literary fiction is something very few of my students do.

What they reliably do is watch movies and television. I’m not sure if I’ve encountered a student who doesn’t. When I was in college — this is the last time I’ll allow myself this indulgence — I remember few conversations about television and little time spent watching it. There was a TV in the communal lounge, but it was a shabby space relative to the temptations elsewhere. To be fair, television has improved since I was a student. David Chase’s The Sopranos and David Simon’s The Wire, everyone seems to agree, raised the bar for what a television show could be. One can debate Simon’s characterization of The Wire as a “visual novel,” but for some of my students, it’s the only novel they choose to consume.

What they reliably do is watch movies and television. I’m not sure if I’ve encountered a student who doesn’t. When I was in college — this is the last time I’ll allow myself this indulgence — I remember few conversations about television and little time spent watching it. There was a TV in the communal lounge, but it was a shabby space relative to the temptations elsewhere. To be fair, television has improved since I was a student. David Chase’s The Sopranos and David Simon’s The Wire, everyone seems to agree, raised the bar for what a television show could be. One can debate Simon’s characterization of The Wire as a “visual novel,” but for some of my students, it’s the only novel they choose to consume.

I have my students read a lot of stories. I make a point, as most instructors do, to vary the subjects and styles, to include authors of different ages, ethnicities, genders, classes, and backgrounds. Every two years I change all of the stories, so I’m not flying on autopilot. There is no shortage of incredible short fiction. The students digest the stories dutifully. Sometimes students are visibly moved in class, which visibly moves me. These mutually-moved moments don’t happen all of the time. I’ve learned to appreciate them.

When a student really likes a story, she will often compare it to a favorite episode, and then this happens:

“It totally reminds me of the Dexter when he —”

“Oh my God, I’m obsessed with that show.”

(General murmurs of approval.)

“Have you seen the one where he [kills someone in a mildly unpredictable way for morally dubious reasons]?”

“That one is amazing.”

Nobody says she is obsessed with Denis Johnson.

My students love Dexter. I have watched enough episodes to conclude I do not love Dexter, though it’s an interesting case study, as it attempts to communicate the protagonist’s inner life. This is harder to do on the screen than on the page, and while I applaud the show’s writers for taking this aspect seriously, the character’s monologues strike me as clumsy and inorganic. They’re supposed to be funny, but they’re not funny.

My students love Dexter. I have watched enough episodes to conclude I do not love Dexter, though it’s an interesting case study, as it attempts to communicate the protagonist’s inner life. This is harder to do on the screen than on the page, and while I applaud the show’s writers for taking this aspect seriously, the character’s monologues strike me as clumsy and inorganic. They’re supposed to be funny, but they’re not funny.

I have yet to find a voiceover that doesn’t make me cringe. As great as Vertigo is, the voiceover bums me out every time. I feel like Hitchcock doesn’t trust me — or his filmmaking — enough, and I’m thrown out of what John Gardner calls the “vivid and continuous dream.” If American Hustle wins a bunch of academy awards, it will be in spite of the lazy voiceover.

Good fiction grants you sustained, nuanced entry into a character’s mind that is difficult to achieve on the screen. This is one of the reasons the best books rarely translate into transcendent films, no matter how many times studios try (e.g. The Great Gatsby). It’s also why some of the best films come from books that aren’t universally regarded (e.g. The Godfather). That The Godfather works better as a film than a book doesn’t diminish the story. Film and literature aren’t interchangeable, and watching the former isn’t necessarily going to help you write the latter. Indeed, it may give you some bad habits. In the classroom, I regularly find myself contradicting the students’ first teacher, the screen.

Good fiction grants you sustained, nuanced entry into a character’s mind that is difficult to achieve on the screen. This is one of the reasons the best books rarely translate into transcendent films, no matter how many times studios try (e.g. The Great Gatsby). It’s also why some of the best films come from books that aren’t universally regarded (e.g. The Godfather). That The Godfather works better as a film than a book doesn’t diminish the story. Film and literature aren’t interchangeable, and watching the former isn’t necessarily going to help you write the latter. Indeed, it may give you some bad habits. In the classroom, I regularly find myself contradicting the students’ first teacher, the screen.

Each Law and Order episode begins with the short dramatization of a crime. Those two minutes set the tone for the rest of the hour. The showrunner makes a contract with the audience before each episode: There will be a crime, it will be investigated, there will be red herrings, but the crime will be solved. Although the characters are more or less the same from episode to episode, the crimes are self-contained. Clearly, this formula works. It’s hard to find someone who hasn’t enjoyed an episode of Law and Order. I particularly enjoy the halcyon days of Special Victims Unit with Christopher Meloni, Mariska Hargitay, Ice-T, and BD Wong, whom I regard as a master of deadpan.

What I don’t enjoy are short stories inspired by SVU. Meloni and Hargitay are fine actors, but on the show, their inner lives are straightforward. They’re driven by primal and singular impulses. The world they inhabit offers little complexity. Sex offenders are bad. Detectives are good. Sometimes good people have to do bad things to get bad guys; that’s about as morally ambiguous as the show gets. It also has a fetish for vigilantism that I don’t share.

One of the most common student stories begins with a scene of violence. It’s unclear who is involved, or why they’re doing what they’re doing. Typically, nobody is named. There’s a space break signifying a leap in time and place, and then the story unfolds in a linear fashion. By the end, the villain (easier to spot than the writer imagines) is apprehended, often with a bit of insufferable banter. The story doesn’t work. My students didn’t learn this formula from reading.

I reference the stories we read. Look where Raymond Carver starts his story. What is all of the protagonist’s furniture doing on the front lawn? Why does Mary Robinson have the strange woman stop by the house on the second page? Start the story as late in the action as you can, I tell my students. Make sure your protagonist wants something, even if only a glass of water. I tell them Kurt Vonnegut gave me this advice. Some of them read Slaughterhouse Five in high school. We’re getting somewhere. Did you read any of his other books? Blank stares.

I reference the stories we read. Look where Raymond Carver starts his story. What is all of the protagonist’s furniture doing on the front lawn? Why does Mary Robinson have the strange woman stop by the house on the second page? Start the story as late in the action as you can, I tell my students. Make sure your protagonist wants something, even if only a glass of water. I tell them Kurt Vonnegut gave me this advice. Some of them read Slaughterhouse Five in high school. We’re getting somewhere. Did you read any of his other books? Blank stares.

Ideally, the stories I assign and recommend will lead my students to read fiction on their own. Sometimes this happens. They take other classes with me, stop by my office hours, write me emails. Few things make me happier than students from past semesters soliciting books. I hope they’re still writing, but if they’re only reading, they’re enlarging their sense of human experience. They’re becoming more empathetic and, in turn, better brothers and sisters, sons and daughters, boyfriends and girlfriends. I believe this.

Most students I never hear from again. We get fifteen weeks, twice a week, eighty minutes a class. It’s not a lot of time to inspire a lifetime of reading. It’s not a lot of time to give students a framework from which they might begin to construct meaningful stories on their own.

Each student writes two stories for my class, but the time he or she spends thinking about the published stories I assign is arguably more important. Students who haven’t taken many writing or literature classes at the university will likely arrive with few reference points, and I treat each story as an opportunity to teach students about character or structure or language. When students reference television shows, I counter with stories. If the story isn’t protected by copyright, I’ll post a link to Blackboard. Anyone can read Anton Chekhov’s “Gusev” or James Joyce’s “Araby” or Alice Munro’s “The Bear Came Over the Mountain” for free online. Publishers mail me unsolicited books all of the time; I give the good ones to my students.

Sometimes when students reference television shows, I go with it. I ask students what they like about the show and what, if anything, they might apply to their writing. If I admire the film they reference, and I think it offers something narratively rewarding, we discuss why. Occasionally, I reference a moment in a film, for better or worse. The Third Man delays the introduction of the antagonist in a way that’s supremely effective (it doesn’t hurt that Graham Greene wrote the screenplay). I rather like Lost in Translation, but the scene where Bill Murray whispers something unheard to Scarlett Johansson strikes me as a narrative betrayal. The writer and character, I’ve told them, shouldn’t know more than the reader. Like all teachers, I’m happy when students intelligently disagree.

In their own stories, I encourage students to write something that makes them uncomfortable. If they’re going to write autobiographically, and many do, they have to be prepared to show their worst characteristics. Probably, the protagonist should do something stupid or ugly. That’s what the reader wants. If they’re going to make something up completely, and I encourage this, they have to move beyond formula. If they crib a violent scene from The Walking Dead, I give them Flannery O’Connor. It’s no less gruesome.

My students are curious in my own tastes, to an extent. What do I like to watch? I tell them. I pair the film with a book. They want to know why the book is always better than the movie. They’re referring to Harry Potter or The Hunger Games. They’ve been told this so many times they believe it, even if they don’t see it personally. It’s because your imagination is so much more interesting than what’s on the screen, I tell them. They don’t buy it. Their interest wanes. The reader and the writer co-create the story, I insist. Reading is collaborative in a way that watching a screen isn’t. You prefer your image to the director’s, no matter how beautiful Jennifer Lawrence might be. You’re narcissistic that way. It’s okay.

They nod reluctantly, like maybe it is.