1.

The year is 1984, and in the quiet center of a declining Midwestern city, the Indians start to appear. They loiter on skybridges over otherwise dead downtown streets. They pose for snapshots in front of the train station, gather in saris for picnics on the hill beneath the art museum. An Indian princess suddenly marries the heir to a local brewery. At the annual Veiled Prophet Ball, where the city’s elite honors one of its own, the Prophet’s throne stands empty. Most mysteriously of all, after the city’s longstanding police chief retires, he passes over local candidates to select an unknown woman from Bombay as his successor. “The city was appalled,” the novel begins, “but the woman — one S. Jammu — assumed the post before anyone could stop her.”

The year is 1984, and in the quiet center of a declining Midwestern city, the Indians start to appear. They loiter on skybridges over otherwise dead downtown streets. They pose for snapshots in front of the train station, gather in saris for picnics on the hill beneath the art museum. An Indian princess suddenly marries the heir to a local brewery. At the annual Veiled Prophet Ball, where the city’s elite honors one of its own, the Prophet’s throne stands empty. Most mysteriously of all, after the city’s longstanding police chief retires, he passes over local candidates to select an unknown woman from Bombay as his successor. “The city was appalled,” the novel begins, “but the woman — one S. Jammu — assumed the post before anyone could stop her.”

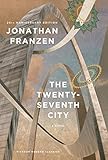

The Twenty-Seventh City was published twenty-five years ago this month by a young writer named Jonathan Franzen. The book’s cover reflected the soaring ambitions of its author, an antiquated skyline dominated by an outsized Gateway Arch and a female face staring out intesely from under her bindi, sometimes called a third eye. The city was St. Louis — once the fourth largest city in the U.S., it had dropped to twenty-seventh by 1988 — helpfully rendered on a map inside the front cover as if it were a fantasy novel, the Midwest as Middle Earth. And in some ways it was a fantasy, the dark twisted fantasy of a native son.

Wasting little time, S. Jammu begins reconfiguring the political landscape. Her immediate goal is to restore St. Louis to its former glory by reintegrating the city with the more affluent and powerful county, from which it split off in the late 19th century. To this end, she funnels millions of foreign dollars into real-estate speculation on the city’s north side. She quickly converts the mayor, gains traction with the black community, and co-opts prominent business and governmental leaders to her cause. Along with her accomplices, most notably a decadent radical named Singh, she enacts a subversive program inspired by Indira Gandhi’s martial-law-like crackdown, the Emergency. The homes of prominent St. Louisans are bugged. When coercion and bribery fail, the arrivistes are not afraid to resort to car bombs, roadblocks, and paramilitary strikes — what might be called limited acts of terror.

The only man that stands in Jammu’s way is Martin Probst, a contractor from Webster Groves, the inner-ring suburb where Franzen grew up. A contractor who worked on the iconic Arch, and the widely respected leader of the civic-improvement organization Municipal Growth, Probst is a noble capitalist Ayn Rand could almost love (he defeated the unions but probably treats his employees too well). Probst distrusts Jammu and leads the opposition to her takeover of the city. This drives Jammu and Singh to extraordinary measures: they will attempt to induce “the State” in Probst. The State is in a shattered, vulnerable condition “in which a subject’s consciousness became extremely limited.” Singh’s account of the operation is chilling:

As a citizen of the West, Probst was…sentimental. In order to induce the State in him, it might be necessary only to accelerate the process of bereavement, to compress into three or four months the losses of twenty years. The events would be unconnected accidents, a “fatal streak”…lasting only as long as it took Probst to endorse Jammu publicly and direct Municipal Growth to do likewise.

Probst’s “fatal streak” begins with the death of the family dog, and escalates to the choreographed estrangement of his teenage daughter, who moves into the apartment of a young photographer. When Probst refuses to bend, Singh kidnaps his wife, Barbara. From its premise the novel extracts a ruthless set of consequences, spelled out in technocratic and emotionless prose — a technique that very effectively creates sympathy for the Probst family and its embattled patriarch. Probst is a flawed but decent man, devoted to his family and his privacy: his most characteristic expression is an awkward “well!” Even as Probst’s family falls apart, the peripheral characters in his life close in, such as his old and pitiable high school friend Jack DuChamp, the excellently unhinged gardener Mohnwirbel, and the right-wing lunatic General Norris (in this book, Norris has it all right). These characters seem like the repressed specters haunting Probst’s orderly American mind. What is stripped away by the conspiracy against him, and by extension the novel itself, is his “wellness,” his comforts and psychic embankments. It is not until his memorably germ-infested visit to a shopping mall on Christmas Eve that he recognizes what has happened to him: “He was sick, and the city was sick on the inside too, choking on undigested motives, racked by lies”

2.

It was a long, dense, problematic novel about a city not exactly at the center of the nation’s consciousness, then or now. Nevertheless, Franzen’s debut was widely reviewed and, for the most part, highly praised. Richard Eder’s rave in the Los Angeles Times was titled “America’s History May Not Be Written by Americans.” In the New York Times, Michiko Kakutani was more ambivalent, noting that “the storyline about a charismatic, Marxist-indoctrinated woman’s attempt to seize control of an American city by using terrorist tactics…sounds like a red-baiting, paranoid nightmare come true.” Neither response fully captured the anger of the novel or the extent of Franzen’s imaginative allegiance with the outsiders.

The local media saw it differently. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch ran a defensive article about Franzen entitled “Don’t Judge by Cover: Author Likes His Hometown.” Referring to the first edition’s cover art, but implicitly to the novel itself, the Post asked: “Why so much distortion? Why would a son of St. Louis be so hard on his hometown?”

Franzen’s deeply ambivalent portrait of the city provokes these questions, and also exposes the bind of the first-time Midwestern novelist: even while the speculative plot unleashes chaos on St. Louis, the city itself is rendered with a wealth of local detail which I imagine will be exhausting to many coastal readers. Franzen builds up and dismantles the city at once, using a sinuous omniscient voice that glides between the locals and the plotting Indians (Jammu and Singh evoke the city’s imperial past when they attribute their terrorist acts to a front group called the Osage Warriors). It’s interesting to learn that the character Jammu was imported from a play Franzen wrote at Webster Groves High School. Behind the Pynchonesque conspiracy, there is an adolescent revenge fantasy at the novel’s heart, which produces some of its most inspired scenes: a suburban family taking cover as their windows shatter with gunfire, an explosion in a TV station parking lot, mass panic at a pro football game. Franzen reimagines the Midwest as an oddly theatrical war zone where terror is a fact of life. But the novel also makes us feel the loss of the Probsts’ rich, cluttered domestic life in Webster Groves, a history that readers must infer almost archeologically from its ruins. If it was possible to write a book of violent nostalgia, Franzen had succeeded.

3.

My wife and I were surprised to find how much we liked St. Louis, after we moved here in the fall of 2004. We knew very little beyond the ominous reports that had filtered through the national media. “All cities are ideas,” Franzen writes. “They create themselves, and the rest of the world apprehends them or ignores them as it chooses.” By the time we arrived, the twenty-seventh city had fallen to the fifty-second (it is now the fifty-eighth). What we encountered was a vexed landscape, a crumbling but also rebuilding city which welcomed us into its project of rehabilitation. I read Franzen’s novel as a primer, a narrative of tragic decline, from the eclipse of St. Louis by Chicago in the 1870 census and the city’s shining moment at the 1904 World’s Fair, to de-industrialization, white flight, the demolition of the notorious Pruitt-Igoe housing complex in the 1970s. Still, we’d never seen structures of such peculiar spectral beauty as the looming red-brick buildings that seemed to line every St. Louis street. While the city’s inequalities could be disorienting, a single wrong turn taking you from stable neighborhoods to areas of surreal devastation, it was also a fascinating place. We felt like we were living someplace where we could matter. After graduating with her master’s degree in urban planning, my wife found work managing data and making maps for a nonprofit that revitalized low-income neighborhoods. Despite the city’s rumored insularity, we grew connected and invested here, and within a few years we bought a house, adopting the city and its problems as our own.

In March 2008, on her way home from work, my wife was attacked on a quiet street just blocks from our house. What began as a mugging devolved into sexual assault. (She later brilliantly documented how the attack altered her mental map of the city on her blog.) A few days later, the police caught up to the perpetrator and arrested him in the bird sanctuary of a nearby park. He pled guilty to all charges, sparing my wife from testifying at his trial, so in this limited, legal sense, everything was resolved. Yet at the same time, over the months and years to follow, she was haunted by the experience in State-like ways. And while her experience remained fundamentally unimaginable to me, no matter how many times I replayed her description in my head, my confusion and anger became its own kind of State, so that I would join her there. It was impossible not to think of her as I reread the passages about Barbara Probst’s captivity in a desolate East St. Louis warehouse. To maintain the charade that Barbara has left Probst for him, Singh dictates her weekly phone calls to her husband, and as artificial as they are, these scenes do actually capture the distortion, the brittleness that can enter a relationship after a trauma. It never felt like we were alone in those days, as if our conversations were being filtered through an interpreter. We could feel, with Probst, that “the whole city [was] a thing of foreignness and menace.” We turned off the news: every report of violence — and these were violent post-recession years in St. Louis — resounded with suddenly personal import. My wife carried a timetable of civil twilight so that we would never be caught outside after dark; in the dark we stayed home and watched TV, something safely fictional. Guilt filtered into our daily lives, leading us to question our most basic acts, until we felt culpable in our mere presence. We wondered if our earlier enthusiasm for St. Louis wasn’t naive. At one point, Franzen writes of Barbara Prost: “This was the worst pain of all, that the world seethed with motives she could never grasp.” While we eventually emerged, and saw the attacker as an individual rather than a malign force, his crime something that could have occurred anywhere, the city never looked exactly the same.

4.

It was another St. Louisan, T.S. Eliot, who wisely said that humankind cannot bear very much reality. I certainly can’t. Books serve me both as a way to confront and avoid real difficulty, and my wrenching ambivalence about The Twenty-Seventh City probably results from the ways it hits too close to home and doesn’t allow me to escape. There is something unsettling about the novel’s tentacular hold on my own experience in the city it depicts. Books can become essential to us in strange and invasive ways, almost against our will.

Franzen continues to have a remarkable ability, both as a writer and a persona, to touch nerves, and his divisiveness is surely a sign of his strength. While I’ve enjoyed all of Franzen’s subsequent work and recognize the technical gains he has made as a storyteller, nothing has moved me personally like his first novel. “I was trying to write an uncanny book,” Franzen told The Paris Review. “A book about making strange a familiar place…that was the feeling I was after…what kind of weird, surreal world have I fallen into here, in the most boring of Midwestern cities?” Well, I disagree about the boring part, and I think The Twenty-Seventh City succeeds, insofar as it does, not only by making St. Louis strange but by drawing out the latent strangeness in the city’s history. The audacity of Franzen’s project still resonates in the city today — a local developer’s north-side regeneration project bears an uncomfortable resemblance to Jammu’s land grab — and its visionary streak stands as something of an unfulfilled promise in his later work. It will be reissued in November as the first Picador Modern Classic.

“Only St. Louis knew,” Franzen writes. “Its fate was sealed within it, its special tragedy nowhere else.” The narrative of tragic decline is seductive in its own way, partly because it relieves the mourner from the responsibility of forming new conspiracies to make the city better. All cities are ideas, and St. Louis’s struggle, as in other Midwestern cities, is partly the mental one of convincing itself that it is not specially doomed. Looking closely, there are definite signs of progress: new residents downtown, an undersung art scene, community development on the north side, consolidation of chambers of commerce and law-enforcement functions. There is even some renewed talk of a Great Reconciliation between the city and the county. The Twenty-Seventh City itself ends darkly in a series of ironic anticlimaxes, reflecting the growing cynicism of the young man from Webster Groves. After almost a decade here, I understand how this city could have driven Franzen nuts and broken his heart. It’s hard to say how long we’ll stay in St. Louis, but despite all its obvious issues, despite everything, we’ll always be rooting for this town. It’s harder to say what I think of The Twenty-Seventh City. Reading it again, I experience its pervasive uncanniness, the sense of being somewhere close to home, but not quite. It also makes me a bit sad, almost as if I’m reading a posthumous work. That St. Louis kid is long gone.