1.

Some years ago, before my first novel found its eventual home, several editors in a row said the book was “too quiet.” I was told at the time that this was just a euphemism for “no obvious marketing angle,” but I found it interesting to consider the idea that some novels are quiet, whereas others are loud.

2.

In her exquisite memoir, The Faraway Nearby, Rebecca Solnit writes movingly of Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein. Shelley gave birth to four children, but only the fourth survived. “In the years she gave birth to all those too-mortal children,” Solnit writes:

In her exquisite memoir, The Faraway Nearby, Rebecca Solnit writes movingly of Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein. Shelley gave birth to four children, but only the fourth survived. “In the years she gave birth to all those too-mortal children,” Solnit writes:

…she also created a work of art that yet lives, a monster of sorts in its depth of horror, and a beauty in the strength of its vision and its acuity in describing the modern world that in 1816 was just emerging. This is the strange life of books that you enter alone as a writer, mapping an unknown territory that arises as you travel. If you succeed in the voyage, others enter after, one at a time, also alone, but in communion with your imagination, traversing your route. Books are solitudes in which we meet.

But before the meeting comes the solitude, the book as a private space that a reader steps into, and nowhere is this clearer to me than on the subway. On any given morning, a majority of my fellow passengers are reading. It’s a way to pass the time, of course, but it seems to me that escaping into a book in these moments is also a bid for some measure of seclusion.

In the places where everyone drives, the roads fill with single-occupancy vehicles in the mornings and the late afternoons, thousands or millions of drivers in their solitudes. On a subway commute, packed in with strangers in an underground train, solitude is more elusive. We resort to small tricks to find some space for ourselves: the noise-blocking headphones, the iPad, the book. I wear earbuds on my commute, but unless I’m too tired to read or the person next to me is loud, the iPod in my pocket is dark. I just want things to be a little quieter, so that I can disappear into my book more fully. In those moments I just want to be a little more alone.

It probably goes without saying that you’ll crave different solitudes at different moments in your life, both in books and in physical places. I have an immense love for loud books. Novels like, say, Nick Harkaway’s, about which I’ve rhapsodized at length, books that come galloping into your life with their doomsday machines and schoolgirl spies and ninjas and leave you daydreaming for days afterward about clouds of mechanized bees. But on the other end of the spectrum, there’s the immense pleasure of novels like Teju Cole’s Open City, which I finally got around to reading a few weeks back. Very little happens in Open City, plotwise. It’s a very intelligent meditation on memory, dislocation, family, music, national identity, and other interesting topics, but the action is mostly a man wandering the streets of New York. I found it mesmerizing.

It probably goes without saying that you’ll crave different solitudes at different moments in your life, both in books and in physical places. I have an immense love for loud books. Novels like, say, Nick Harkaway’s, about which I’ve rhapsodized at length, books that come galloping into your life with their doomsday machines and schoolgirl spies and ninjas and leave you daydreaming for days afterward about clouds of mechanized bees. But on the other end of the spectrum, there’s the immense pleasure of novels like Teju Cole’s Open City, which I finally got around to reading a few weeks back. Very little happens in Open City, plotwise. It’s a very intelligent meditation on memory, dislocation, family, music, national identity, and other interesting topics, but the action is mostly a man wandering the streets of New York. I found it mesmerizing.

Lately, possibly because it’s been a long summer of continuous hard work on a new novel and I don’t want to think about plot just now, or perhaps because my annual allotment of vacation days at my day job resets every September 1st, I’ve been out of vacation time since February, and reading quiet books is the closest I can get to a vacation at the moment, I’ve discovered a new appreciation for books that fall on the quieter end of the spectrum.

3.

Any definition of what constitutes a quiet book will naturally be subjective, but I think the important point here is that quiet isn’t the same thing as inert. I’m not talking about the tediously self-conscious novels written by authors who use “literary fiction” as a sort of alibi, as in “my book doesn’t have a plot, because it’s literary fiction.” I rarely get more than fifty pages into these books before they join the books-that-need-to-get-out-of-my-apartment-immediately pile by the front door. Nor is quiet necessarily the same thing as minimalist. Raymond Chandler’s prose is minimalistic, but his stories aren’t quiet.

The books I think of as being quiet, the ones I’ve been enjoying lately, have a distilled quality about them, an unshowy thoughtfulness and a sense of grace, of having been boiled down to the bare essentials. If the solitude you crave at the moment is a quiet one, here’s a short reading list of quiet books that I’ve recently read and admired:

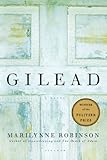

1. Gilead by Marilynne Robinson

1. Gilead by Marilynne Robinson

The book takes the form of a letter written by an aging Congregationalist minister, John Ames, to his young son. I found the language extraordinary.

2. Open City by Teju Cole

A young psychiatrist, Nigerian-born, walks the streets of New York City. The walks open the city to him and serve as a respite from the stress of his working life.

3. Snow Hunters by Paul Yoon

A North Korean man defects and immigrates to a coastal town in Brazil following the Korean War, where he becomes a tailor’s apprentice. An elegant account of a quiet and solitary life.

4. The Number of Missing by Adam Berlin

A deeply moving chronicle of drinking, friendship, and grief. Paul was among the scores of Cantor Fitzgerald employees who died in the World Trade Center. In the months following the 9/11 attacks, his best friend, David, moves like a ghost between the bars of Manhattan, sometimes with and sometimes without Paul’s widow, Mel. Both are falling, but David is waiting for Mel to fall first, so that he can catch her.

5. The Summer Book by Tove Jansson

5. The Summer Book by Tove Jansson

Sophia, age six, and her grandmother, who’s nearing the end of her life, while away the days of a summer on a remote island in the Bay of Finland. Jansson’s depiction of both characters and of their relationship is delightful.

6. The Harp in the South by Ruth Park

A classic in Australia. A couple raise their children in the slums of 1940s Sydney, “in an unlucky house which the landlord had renumbered from Thirteen to Twelve-and-a-Half.”

Image via Michael Veltman/Flickr