In the four months since my book was published, I’ve given speeches to everyone from hipsters in Williamsburg to an international audience in Holland. I have stood behind wooden podiums to deliver lectures to university students and have worked myself into a near heart attack before being interviewed for morning television. By no means is this unusual. Most authors are bound to talk about their books in settings from bookstores to classrooms. Many authors are introverted creatures that are not naturally inclined to presenting in front of large groups. And yet, I will hazard that my experience is a little different than most. Against any trajectory I would have imagined for my life, I have become this oxymoronic creature, a stuttering public speaker.

In the four months since my book was published, I’ve given speeches to everyone from hipsters in Williamsburg to an international audience in Holland. I have stood behind wooden podiums to deliver lectures to university students and have worked myself into a near heart attack before being interviewed for morning television. By no means is this unusual. Most authors are bound to talk about their books in settings from bookstores to classrooms. Many authors are introverted creatures that are not naturally inclined to presenting in front of large groups. And yet, I will hazard that my experience is a little different than most. Against any trajectory I would have imagined for my life, I have become this oxymoronic creature, a stuttering public speaker.

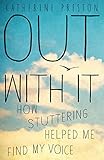

My book, Out With It: How Stuttering Helped Me Find My Voice, recounts the journey that I went on to come to terms with my stutter. Having spent years of my life battling against my speech and wanting to be normal, I spent a year traveling around America talking to hundreds of stutterers, researchers, and speech therapists, trying to find answers. I planned to write a journalistic investigation, to hide behind the role of narrator while I safely penned a book of oral histories. And yet, in the process of writing Out With It, I realized that my safe book of interviews was neither doing justice to those people who had so courageously told me their stories, nor was it doing justice to the type of writing I thought I could accomplish. So I radically changed the book and I rewrote it as a memoir, making my life the thread that wove all our stories together.

Out With It was not the type of book anyone imagined I would write. If you asked any of my friends to describe me they would probably paint a picture of a very private person. I was brought up in England and unabashed feelings tended to make me a little awkward. I imagined they were the realm of those mushy Americans. Dirty laundry was dealt with at home. Love and hate were all expressed in private, away from prying eyes.

But of all the parts of myself that I hid, I hid my stutter the most fervently. Not that my stutter was easily disguised, I’m too verbose and I stutter too often for that ever to be the case, but its effect on me was relatively easy to hide. I laughed it off, and brushed it off, in the hope that if I didn’t draw attention to it, everyone would simply stop noticing. If my mum ever saw through my less-than-convincing act, I would shout at her for long enough that she no longer had the energy to try and peel away the layers of my shell. For years, I protected myself that way.

And then I wrote Out With It. In order to write the best book I could, I had to unearth all the pieces of my life that I had ignored. I dredged up dusty memories and stared at them for long enough that they came into focus. I asked my parents questions and listened to their answers. I reread scribbled and stained diary entries and started to type up my life. I recreated the scenes I could remember, put myself back in the shoes of my earlier selves, and analyzed the sound of my stuttered voice to capture its staccato rhythm on the page. In order not to hide, I thought of myself as a character.

On the day that Out With It was published I remember feeling a huge sense of vulnerability. I was thrilled that it was finally making its way into the world, and yet I fretted about what people would think of me. What would they read into my story? Would anyone read it at all? I was desperate to control the way the world would see me.

And yet it turns out that I was worrying about entirely the wrong thing. It seems that writing a vivid book about stuttering, a book that people read in the privacy of their own lives, is only one level of vulnerability. Standing up to speak about that book, while experiencing the sensation of stuttering and bearing witness to all the immediate reactions that evokes, is quite another.

I watch my audience obsessively when I speak. I watch them laugh, and cry, I see people nod their heads fervently and whisper unheard asides to their friends nearby. The times that I have stuttered the most I have been met with steady eyes and standing ovations. My habitual reaction is to yearn for fluency, and yet the times that I’ve stuttered the least have resulted in yawns and the bored tapping of fingers on blue screens. I have realized that people want to see the “character” of my book up on stage. They want to see stuttering, to feel its curious intensity. I want that too. I want to acknowledge that stuttering exists, that it is nothing to be frightened of. I want to use the candid truthfulness of my speeches to build bridges between us. I aspire to give them what they want, and yet I also crave the rhythmic seduction of language that I find much easier to create on the page. I slip back into my habitual wish to control the atmosphere created by my words.

When I’m standing on stage, I often think about the writer David Shields. Both in conversation, and when he addresses a crowd, there is a remarkable similarity between his writing and his speech. Another stutterer, though not a memoirist, Shields’s writing style is dubbed as collage. In his work, he draws on everything from author quotes to film scenes, and his aim is to eliminate the novelistic facade of plot. In person, he speaks similarly in associations and has no qualms mentioning everything from the “cheat sheet” he’s holding in his hand to his barely stuttered speech. I think of his lack of artifice whenever I’m tempted to turn my speech into a performance and hide behind some coy, over-polished veneer.

The poet Forrest Gander writes that “the best we can do is to try to level ourselves unprotected.” He believes that we should approach the world with as much vulnerability as we can sustain. Memoirists open themselves up to the process of self-discovery, they make art out of the chaos of a life lived. We write to resonate with the souls of others. When the memoirist stands on stage, we are made aware of the connection between product and producer. When I stand on stage, I’m well aware of our tentative separation and our potent connection. Public speaking forces me, and my audience, to witness the messy tug of myself, to see both the struggle and the strength of my speech. It pushes me out of my private cocoon and forces me to trust my audience, to remain cracked open.

I’m lucky to have the choice to speak up about stuttering, to be given the stage. I’m lucky that people want to hear my voice, to be ushered into a world that sounds different to theirs. We live in a world where stuttering gets very little press. It is a condition that, quite literally, finds it difficult to make itself heard. I believe that needs to change. In order to do that, I know that I need to speak up, to push myself towards the microphone, and voice all my hard-crafted words.