I would dearly love to be able to start this piece by saying that

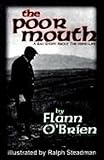

The Poor Mouth is the funniest book ever written. It’d be a real lapel-grabber, for one thing, an opening gambit the casual Millions reader would find it hard to walk away from. And for all I know, it might well be true to say such a thing. Because here’s how funny it is: It’s funnier than A Confederacy of Dunces. It’s funnier than Money or Lucky Jim. It’s funnier than any of the product that any of your modern literary LOL-traffickers (your Lipsytes, your Shteyngarts) have put on the street. It beats Shalom Auslander to a bloody, chuckling pulp with his own funny-bone. And it is, let me tell you, immeasurably funnier than however funny you insist on finding Fifty Shades of Grey. The reason I can’t confidently say that it’s the funniest book ever written is that I haven’t read every book ever written. What I can confidently say is that The Poor Mouth is the funniest book by Flann O’Brien (or Myles na gCopaleen, or any other joker in the shuffling deck of pseudonyms Brian O’Nolan wrote under). And if this makes it, by default, the funniest book ever written, then all well and good; but it is certainly the funniest book I’ve ever read.

The Poor Mouth is the funniest book ever written. It’d be a real lapel-grabber, for one thing, an opening gambit the casual Millions reader would find it hard to walk away from. And for all I know, it might well be true to say such a thing. Because here’s how funny it is: It’s funnier than A Confederacy of Dunces. It’s funnier than Money or Lucky Jim. It’s funnier than any of the product that any of your modern literary LOL-traffickers (your Lipsytes, your Shteyngarts) have put on the street. It beats Shalom Auslander to a bloody, chuckling pulp with his own funny-bone. And it is, let me tell you, immeasurably funnier than however funny you insist on finding Fifty Shades of Grey. The reason I can’t confidently say that it’s the funniest book ever written is that I haven’t read every book ever written. What I can confidently say is that The Poor Mouth is the funniest book by Flann O’Brien (or Myles na gCopaleen, or any other joker in the shuffling deck of pseudonyms Brian O’Nolan wrote under). And if this makes it, by default, the funniest book ever written, then all well and good; but it is certainly the funniest book I’ve ever read.

And I’ve read it maybe five or six times at this point: first as a teenager, then again as an undergraduate when I was supposed to be reading other much less funny things, and then again another couple of times while writing a Masters thesis – a terrific wheeze of a Borges/O’Brien comparative reading. And I’ve just now revisited it afresh, partly to reassure myself before writing this piece that it is just as funny as I remember it being. (It is, albeit with the slight caveat that it’s possibly even funnier.) The first time I read it, I was in school, and I remember being confounded by two facts: 1) That it was originally published in 1941 and 2) That it first appeared in Irish as An Béal Bocht. And if there was one thing that was less funny than anything written before, say, 1975, it was anything that was written in Irish.

To fully understand this, I think you would probably need to have some first-hand experience of the Irish educational system. This is a country in which every student between the ages of five and eighteen is taught Irish for several hours a week, and yet it is also, mysteriously, a country in which relatively few adults are capable of holding a conversation in the language in anything but the most stilted, self-consciously ironic pidgin. (After almost a decade and a half of daily instruction in the spoken and written forms of what is officially my country’s first language, just about the only complete Irish sentence I myself can now speak translates as follows: “May I please have permission to go to the toilet, Teacher?” I don’t think I’m especially unusual in this regard, although I’m aware my ability to forget things I’ve learned is exceptional.) I don’t want to get into this too deeply here, except to say that part of this has to do with a kind of morbid cultural circularity: the reason so few people speak Irish outside of classrooms is because so few people speak Irish outside of classrooms, and that there would therefore be few people to speak it to if they did. Also, very little literature gets written in Irish, partly because (for the reasons outlined above), relatively few people are capable of writing it, and also because, if they did, the readership for it would be correspondingly small. And so the stuff that gets taught in schools tends to be a combination of (as I remember it) unremarkable contemporary poetry and psychotropically dull peasant memoir.

The great canonical presence in the latter genre is a book called Peig, the autobiography of an outstandingly ancient Blasket island woman named Peig Sayers, which was dictated to a Dublin schoolteacher and published in 1936. Successive generations of Irish students were forced not just to read this exegesis of poverty and misfortune – over and over and over – but to memorize large chunks of it, later to be disgorged and explicated at the intellectual gun-point of state examination. The memoir begins with Peig outlining what a rigorously shitty time she had of it growing up in rural Ireland in the late 19th century, and this unhappy existence is narrated with a signature flatness of tone that is maintained throughout the whole grim exercise:

The great canonical presence in the latter genre is a book called Peig, the autobiography of an outstandingly ancient Blasket island woman named Peig Sayers, which was dictated to a Dublin schoolteacher and published in 1936. Successive generations of Irish students were forced not just to read this exegesis of poverty and misfortune – over and over and over – but to memorize large chunks of it, later to be disgorged and explicated at the intellectual gun-point of state examination. The memoir begins with Peig outlining what a rigorously shitty time she had of it growing up in rural Ireland in the late 19th century, and this unhappy existence is narrated with a signature flatness of tone that is maintained throughout the whole grim exercise:

My people had little property: all the land they possessed was the grass of two cows. They hadn’t much pleasure out of life: there was always some misfortune down on them that kept them low. I had a pair of brothers who lived — Sean and Pádraig; there was also my sister Máire.

As a result of never-ending flailing of misfortune my father and mother moved from the parish of Ventry to Dunquin; for them this proved to be a case of going from bad to worse, for they didn’t prosper in Dunquin no more than they did in Ventry.

For a teenager, of course, the only appropriate reaction to this stuff is the most inappropriate one, somewhere between stupefaction and manic amusement. As real and as comparatively recent as the history of grinding poverty and oppression in Ireland is, it’s still hard to read this with a straight face – particularly if, as a youth, you had to commit great thick blocks of it to memory. There’s something about the improbable combination of sober causality and delirious wretchedness (“As a result of the never-ending flailing of misfortune”; “a case of going from bad to worse”) that comes on like an outright petition for heartless juvenile ridicule. “Nothing is funnier than unhappiness,” as Nell puts it in Beckett’s Endgame. We should take this point seriously, coming as it does from an old woman who has no legs and lives in a dustbin.

Beckett’s contemporary Flann O’Brien understood this, too: unhappiness is the comic goldmine from which he extracts The Poor Mouth’s raw material. He is parodying Irish language books like Peig and, in particular, Tomás Ó Criomhthain’s memoir An t-Oileánach (The Islander); but in a broader sense, he’s ridiculing the forces of cultural nationalism that promoted these books as exemplars of an idealized and essentialized form of Irishness: rural, uneducated, poor, priest-fearing, and truly, superbly Gaelic.

O’Brien’s narrator, Bonaparte O’Coonassa, is not so much a person as a humanoid suffering-receptacle, a cruel reductio ad absurdium of the “noble savage” ideal of rural Irishness promoted by Yeats and the largely Anglo-Irish and Dublin-based literary revival movement. A lot of the book’s funniness comes from its absurdly stiff language (which reflects an equally stiff original Irish), but that language is a perfect means of conveying a drastically overdetermined determinism – a sort of hysterical stoicism which seems characteristically and paradoxically Irish. The book’s comedic logic is roughly as follows: to be Irish is to be poor and miserable, and so anything but the most extreme poverty and misery falls short of authentic Irish experience. The hardship into which Bonaparte is born, out on the desperate western edge of Europe, is seen as neither more nor less than the regrettable but unavoidable condition of Irishness, an accepted fate of boiled potatoes and perpetual rainfall. “It has,” as he puts it, “always been the destiny of the true Gaels (if the books be credible) to live in a small, lime-white house in the corner of the glen as you go eastwards along the road and that must be the explanation that when I reached this life there was no good habitation for me but the reverse in all truth.”

Like many of the best comedians of prose, O’Brien is a master of studied repetition. Again and again, unhappy situations are met with total resignation, with a fatalism so extreme that it invariably proceeds directly to its ultimate conclusion: death. Early on, Bonaparte tells us about a seemingly intractable situation whereby his family’s pig Ambrose, with whom they shared their tiny hovel, developed some disease or other that caused him to emit an intolerable stench, while at the same time growing so fat that he couldn’t be got out the door. His mother’s reaction to this situation is simply to accept that they’re all going to die from the stench, and that they therefore might as well get on with it. “If that’s the way it is,” she says, “then ‘tis that way and it is hard to get away from what’s in store for us.”

Individual hardships or injustices are never seen as distinct problems to be considered with a view to their potential solution; they are always aspects of a living damnation, mere epiphenomena of “the fate of the Gaels.” It’s a mindset that’s both profoundly anti-individualist and cosmically submissive. The cause of suffering isn’t British colonialism: it’s destiny. On Bonaparte’s first day of school, his teacher beats him senseless with an oar for not being able to speak English, and to impress upon him the fact that his name is no longer Bonaparte O’Coonnassa, but “Jams O’Donnell” – a generically anglicized title the same schoolmaster gives to every single child under his tutelage. When Bonaparte takes the matter up with his mother later that day, she explains that this is simply the way of things. The justice or injustice of the situation doesn’t come into it:

Don’t you understand that it’s Gaels that live in this side of the country and that they can’t escape from fate? It was always said and written that every Gaelic youngster is hit on his first school day because he doesn’t understand English and the foreign form of his name and that no one has any respect for him because he’s Gaelic to the marrow. There’s no other business going on in school that day but punishment and revenge and the same fooling about Jams O’Donnell. Alas! I don’t think that there’ll ever be any good settlement for the Gaels but only hardship for them always.

The assumption that nothing can be done about it, though, doesn’t mean that ceaseless meditation and talk about the suffering of the Gaels is not absolutely central to the proper business of Gaelicism. True Irishness is to be found in the constant reflection on the condition of Irishness. (This is still very much a characteristic of contemporary Irish culture, by the way, but that’s probably another day’s work.) O’Brien’s characters think and talk about little else. Bonaparte, at one point, recalls an afternoon when he was “reclining on the rushes in the end of the house considering the ill-luck and evil that had befallen the Gaels (and would always abide with them)” when his grandfather comes in looking even more decrepit and disheveled than usual.

– Welcome, my good man! I said gently, and also may health and longevity be yours! I’ve just been thinking of the pitiable situation of the Gaels at present and also that they’re not all in the same state; I perceive that you yourself are in a worse situation than any Gael since the commencement of Gaelicism. It appears that you’re bereft of vigour?

– I am, said he.

– You’re worried?

– I am.

– And is it the way, said I, that new hardships and new calamities are in store for the Gaels and a new overthrow is destined for the little green country which is the native land of both of us?

O’Brien uses the term “Gael” and its various derivatives so frequently throughout the book that the very idea of “Gaelicism” quickly begins to look like the absurdity it is. This reaches a bizarre culmination in the book’s central comic set-piece, where Bonaparte recalls a Feis (festival of Gaelic language and culture) organized by his grandfather to raise money for an Irish-speaking university. The festival is, naturally, an exhaustively miserable affair, characterized by extremes of hunger and incredibly shit weather. (“The morning of the feis,” Bonaparte recalls, “was cold and stormy without halt or respite from the nocturnal downpour. We had all arisen at cockcrow and had partaken of potatoes before daybreak.”) Some random Gael is elected President of the Feis, and opens the whole wretched observance with a speech of near perfectly insular Gaelicism:

If we’re truly Gaelic, we must constantly discuss the question of the Gaelic revival and the question of Gaelicism. There is no use in having Gaelic, if we converse in it on non-Gaelic topics. He who speaks Gaelic but fails to discuss the language question is not truly Gaelic in his heart; such conduct is of no benefit to Gaelicism because he only jeers at Gaelic and reviles the Gaels. There is nothing in this life so nice and so Gaelic as truly true Gaelic Gaels who speak in true Gaelic Gaelic about the truly Gaelic language.

This is followed by more speeches of equal or greater Gaelicism, to the point where a number of Gaels “collapsed from hunger and from the strain of listening while one fellow died most Gaelically in the midst of the assembly.” From a combination of malnutrition and exhaustion, several more lives are lost in the dancing that follows.

O’Brien’s reputation as a novelist rests largely on the postmodern absurdism of The Third Policeman and At Swim-Two-Birds, with their mind-bending meta-trickery and audacious surrealism. But the essence of his genius was, I think, to be found in his extraordinary mastery of tone, in his skillful manipulation of a kind of uncannily mannered monotony. Repetition and redundancy are absolutely crucial to the comic effect of his prose, and it’s in The Poor Mouth that these effects are most ruthlessly pursued, not least because they are crucial elements of the kind of story he’s parodying here – a life of unswerving and idealized tedium, in which basically the only viable foodstuff is the potato. (Breakfast is memorably referred to as “the time for morning-potatoes.”) There’s a feverish flatness to the narrative tone throughout, a crazed restraint, and a steady accumulation of comic pressure that is like nothing else I’ve ever read. Bonaparte’s recollection of his first experience with alcohol – in the form of poitín, which is of course the potato fermented to the point of near-lethality – is one of the stronger examples of this in the book. It’s also, I think, probably the greatest of O’Brien’s many great comic riffs:

O’Brien’s reputation as a novelist rests largely on the postmodern absurdism of The Third Policeman and At Swim-Two-Birds, with their mind-bending meta-trickery and audacious surrealism. But the essence of his genius was, I think, to be found in his extraordinary mastery of tone, in his skillful manipulation of a kind of uncannily mannered monotony. Repetition and redundancy are absolutely crucial to the comic effect of his prose, and it’s in The Poor Mouth that these effects are most ruthlessly pursued, not least because they are crucial elements of the kind of story he’s parodying here – a life of unswerving and idealized tedium, in which basically the only viable foodstuff is the potato. (Breakfast is memorably referred to as “the time for morning-potatoes.”) There’s a feverish flatness to the narrative tone throughout, a crazed restraint, and a steady accumulation of comic pressure that is like nothing else I’ve ever read. Bonaparte’s recollection of his first experience with alcohol – in the form of poitín, which is of course the potato fermented to the point of near-lethality – is one of the stronger examples of this in the book. It’s also, I think, probably the greatest of O’Brien’s many great comic riffs:

If the bare truth be told, I did not prosper very well. My senses went astray, evidently. Misadventure fell on my misfortune, a further misadventure fell on that misadventure and before long the misadventures were falling thickly on the first misfortune and on myself. Then a shower of misfortunes fell on the misadventures, heavy misadventures fell on the misfortunes after that and finally one great brown misadventure came upon everything, quenching the light and stopping the course of life.

The effort to identify the comic operations of any given piece of writing – what its technology consists of, how its moving parts fit together – is essentially a mug’s game. There’s a hell of a lot to be said for just accepting that something is funny because it makes you laugh. But there’s something about the flawlessness of this passage’s mechanism that makes me want to take it apart and lay out its components. Obviously, repetition is the primary engine here – just the sounds of the words “misadventure” and “misfortune” in such close succession is powerfully amusing. And, as with the spookily O’Brien-esque passage above from Peig, there’s the mix of sober causality and delirious wretchedness. Accumulation and enumeration is, as always with this writer, an irresistible comic force. But I think the real stroke of genius here – the element that really elevates it to the level of the sublime – is how he keeps going well past the point where the joke has done its job. The funniest word here, in other words – the word that always tips me over into literal LOLing whenever I read it – is “Then …”

And maybe this is funny precisely for the least funny of reasons: because misery and misadventure rarely stop at the point where their work is done. Even when misfortune – or life, or history – has already made its irrefutable point, there’s never anything to prevent it taking a quick breath and starting a new sentence: “Then …”

Image via Wikimedia Commons