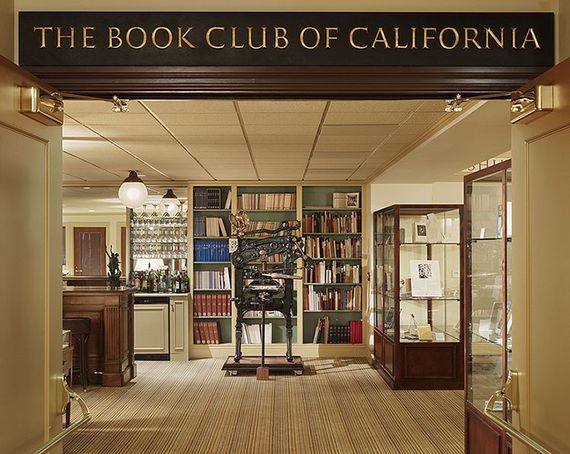

On Monday last, mere days after the announcement of Granta’s fourth installment of young British novelists, I went to hear two of said novelists read at the Book Club of California, one of the great California bibliophilic clubs–a book-lined, womb-like suite of rooms in a building near Union Square.

The novelists, Ross Raisin and Nadifa Mohamed were ferried to California through a joint effort of Granta and the British Council, and feted through the somewhat startling collaboration of the aforementioned Book Club and City Lights Books, venerable but in many ways dissimilar San Francisco institutions.

The Book Club is kept alive by the efforts of patrons who wish to keep old-fashioned pursuits like bookmaking and book collecting and book reading alive. I had been before Monday; I have rolled dollies through its hallways for employers, and bundled up priceless items in bubble wrap while kneeling in the deep nap of its carpet. It is the kind of place where you might encounter a manuscript leaf from The Hound of the Baskervilles, or some press book monumental in its beauty, person-hours, and price. It is clubby, but not snobbish, with weekly programs that are open to the public. It is staffed most of the time by a beautiful poet and a former finance man who has latterly devoted himself to the arts.

The Book Club is kept alive by the efforts of patrons who wish to keep old-fashioned pursuits like bookmaking and book collecting and book reading alive. I had been before Monday; I have rolled dollies through its hallways for employers, and bundled up priceless items in bubble wrap while kneeling in the deep nap of its carpet. It is the kind of place where you might encounter a manuscript leaf from The Hound of the Baskervilles, or some press book monumental in its beauty, person-hours, and price. It is clubby, but not snobbish, with weekly programs that are open to the public. It is staffed most of the time by a beautiful poet and a former finance man who has latterly devoted himself to the arts.

The Book Club is a place of wonders, but it does not generally feel very current. I mean it most affectionately when I say that during the reading you could hear people hack and gurgle, and when the cell phones sounded, which they did rather a lot, it seemed less a function of callow youth than of people who couldn’t figure out how to turn them off, or needed to keep them on for reasons relating to LifeCall.

The Book Club is not hip, but on Monday evening, I felt the spiritual glamour of a place, which, despite its age and sometime pokiness, is founded on the fundamentally sound principle that if you have three glasses of wine in a plastic cup and listen to something beautiful or see it, it can change the whole complexion of the world. The world, as you walk out the door into an unseasonably warm night, and stride down Grant Avenue lined with exquisite narrow buildings, is imbued with possibility.

I was obviously besotted with wine, but also by the talent of Ross Raisin and Nadifa Mohamed and John Freeman, Granta editor, who moderated so smoothly and well that I spent a few moments trying to figure out how old he was, and whether his smoothness was the smoothness of years or divine spark. For my companion and me, the wages of the Book Club’s unhipness were proximity; we sat in the second row, a yard from the podium. Freeman said of the novelists, “In 10 years they won’t be in this room, they’ll be in an auditorium of 500,” and I feel now that this is true, and am grateful for this early-career intimacy.

Both novelists read from their pieces in the current Granta. Raisin, who is the author of God’s Own Country and Waterline, went first and read only part of his story, called “Submersion.” It began without fanfare: “We were out of town, drinking in an empty beachside bar in a small resort down by the coast.” A barman’s patter, a “you,” a television set showing a hard rain. Raisin later told the crowd that he read a lot of Hardy, and Hardy was perceptible a few sentences in, when these seasonal rains were invoked with unexpected pastoralism: “Morris Peake danced in the square. Groups of children ran down to the swollen river to play and smoke and cut channels into Van Stamen’s soft wet fields,” upon which, less pastoral, drowned parsnips eventually floated like “baby’s limbs.”

Both novelists read from their pieces in the current Granta. Raisin, who is the author of God’s Own Country and Waterline, went first and read only part of his story, called “Submersion.” It began without fanfare: “We were out of town, drinking in an empty beachside bar in a small resort down by the coast.” A barman’s patter, a “you,” a television set showing a hard rain. Raisin later told the crowd that he read a lot of Hardy, and Hardy was perceptible a few sentences in, when these seasonal rains were invoked with unexpected pastoralism: “Morris Peake danced in the square. Groups of children ran down to the swollen river to play and smoke and cut channels into Van Stamen’s soft wet fields,” upon which, less pastoral, drowned parsnips eventually floated like “baby’s limbs.”

And then a quick shift to surreality:

The helicopter camera has panned down, and it’s following an object that at first looks like some kind of dark box, but as the image grows closer I see that it is in fact our father, asleep in his armchair, drifting down the high street…Our father is drifting now past the barbershop…the skin on his face is red and peeling, the scalp blistered, hairless…its charred black shape…the remote control deformed and melted onto the armrest.

I found the thing electrifying.

Mohamed, the author of Black Mamba Boy and the upcoming Orchard of Lost Souls, read from a story called “Filsan.” The titular Filsan is a female soldier in the Revolutionary Somali Army, assigned to Hargeisa, where Mohamed herself was born. Like “Submersion,” the story had elegant pacing. The reading began with Filsan and her comrades in a dusty village, where a rebellion is or is not brewing, and the mission is ostensibly to destroy the water supply to save the water supply. The villagers don’t heed Filsan, although she is there “with the full authority of the Revolutionary government.” Later, they heed: she is surprised by the bullets spilled from her own gun, and by the shells of those bullets when they become “bronze beetles scuttling” over her feet. Three men are dead. At the end of the passage, Filsan’s colleague congratulates her while she asks, “What happened? Who killed them?” Again, electrifying.

Mohamed, the author of Black Mamba Boy and the upcoming Orchard of Lost Souls, read from a story called “Filsan.” The titular Filsan is a female soldier in the Revolutionary Somali Army, assigned to Hargeisa, where Mohamed herself was born. Like “Submersion,” the story had elegant pacing. The reading began with Filsan and her comrades in a dusty village, where a rebellion is or is not brewing, and the mission is ostensibly to destroy the water supply to save the water supply. The villagers don’t heed Filsan, although she is there “with the full authority of the Revolutionary government.” Later, they heed: she is surprised by the bullets spilled from her own gun, and by the shells of those bullets when they become “bronze beetles scuttling” over her feet. Three men are dead. At the end of the passage, Filsan’s colleague congratulates her while she asks, “What happened? Who killed them?” Again, electrifying.

After these relatively brief readings, John Freeman took over and asked Raisin and Mohamed about their storytelling influences and motivations. “I’m a Yorkshireman, and I’m from a family of quite quiet, recalcitrant, gruff Yorkshire people,” said Raisin, in what might make a nice, to-the-point epitaph. His formative reading, he reported, ranged from James Herbert and Dean R. Koontz and Stephen King all the way to Graham Greene and the aforementioned Hardy. There is another novelist in his family tree, but not one, evidently, who appears on any Granta lists.

Mohamed talked about her father, a “Forrest Gump” whose stories tended to begin and end in provocative clips like “The last time I had a headache was in Ecuador in 1963.” She spoke of intentionally addressing the “small lives caught up” in history in her writing–people like her father (or a woman, no relation, who saved her whole life to buy an English Bible she couldn’t read, only to be executed for it by Bloody Mary.)

Place came up a lot. It is a central conceit of the Granta list, an enterprise that leaves “Britishness” open to relentless interrogation from all sides. The catholicity of the list, in terms of birthplaces and borders and varieties of government documents, has been remarked upon at length: grumpily, by the right-wingers in The Guardian’s Comment is Free (“Amazing what passes for being British these days isn’t it”), and earnestly, by Granta itself. Freeman sprung surprise passages upon the two novelists to read and show the ever-increasing lexical depth of English: Raisin’s passage in Glaswegian, Mohamed’s invoking jinns and half-men. And then he sprung something even harder, his final question: “How do you feel about Britain today, and if you had to explain to someone who’s been living on the moon for the last 204 years, how the British cosmology of literary life works, how would you do that?” And we all had some laughs and they spoke well and there was no answer, because what is the answer to How British is it?

I thought about places when Raisin quoted the climactic augurs–“If it floods, it floods”–with “flood” shaped the same way as “gruff” (as in “gruff Yorkshire people”). Or when Mohamed read her characters saying “Stop” and “Get back, back, back,” with the full meaning of the words in her delivery, and the texture imparted to the words by her pleasant, infinitesimally stuffy-nosed voice. I thought about places, how people might look at the sky over Somaliland, “counting the stars as they one-by-one bowed and left the stage,” or how a man might dance in Raisin’s rainy town square.

Like all good stories, though, these readings also took me back to my own territory (where, for reasons inscrutable and presumably risible, Raisin’s novel God’s Own Country is called Out Backward). Mostly the associations were grim: hearing Raisin’s passage on helicopter footage of flooded-out people on roofs, what American could fail to think of Katrina? When his beer-drinkers see their be-armchaired, waterborne dad with peeling skin and melted remote, different footage leapt unbidden to mind: the man from last week, photographed in the wheelchair with his legs blown off, whose father found out from the news. At the end of Mohamed’s story, I thought about people who are very young, whom I can’t believe mean for bullets to spray out, or want for things to end with men on the ground and their wives weeping upon them.

Later, I read several peevish things in The Guardian about Freeman, who allegedly maligned Leeds as a provincial outpost in a recent interview. But the first words out of his mouth at the Book Club of California were “I grew up in Sacramento,” which, despite being the former stomping ground of Joan Didion and Raymond Carver, is a somewhat unsexy capital. I know this, having spent a summer toiling behind the hostess stand of the now-defunct Pyramid Alehouse on its main drag, so when Freeman said this, I thought simultaneously I’m surprised and I feel you. And when it was all over I thought about the prosiness and unexpected glamour of places, like Sacramento, or the Book Club of California, 100 years old and hosting world-class novelists I am grateful to have seen in the flesh.

When I got home, still high from the evening’s triumphs, I finally became a member, at the reduced-price rate for the young novel reader.

Image Credit: The Book Club of California