“Is it a book then . . . that you’re working on?”

“I wouldn’t call it a book, really,” Felix replied evenly, his knuckles white on the balcony railing.

“But through all our talks, you’ve never once mentioned it!” the Professor, now truly hurt, blurted mournfully. “How can that be?” Then the question authors dread above all others: “Pray, what’s it about?”

1.

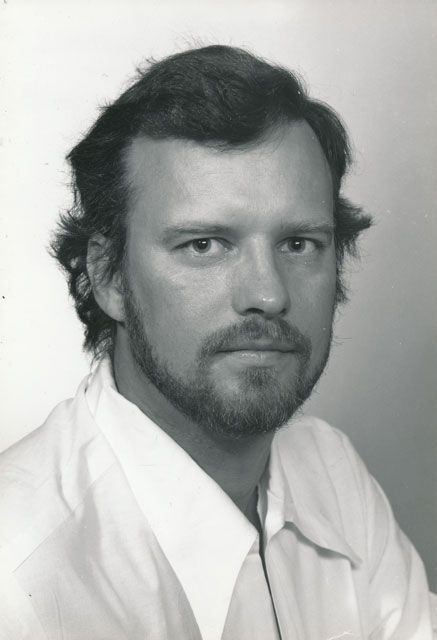

In the summer of 1989, my uncle, the novelist Charles Newman, rented a cottage near the weekend home my parents owned on Cape Cod. Uncle Charlie, as I was still absurdly in the habit of calling him as an 18-year-old, was out of place on the Cape — he avoided the water and lacked a family to indulge at the ubiquitous drive-ins and miniature golf courses. The brand-new black Acura Legacy with gold trim that he had driven all the way from St. Louis, its trunk packed full of high-potency multivitamins and Mahler CDs, stood parked all summer in the cottage’s white, sandy driveway like a rebuke to the entire peninsula. I never went inside the cottage. My mother had instructed me to not even drive down the street when Charlie was working, which was always, and to never under any circumstances ask what he was working on. After the summer ended, though, we inferred that it had been productive. Charlie was sober, stable, and had been quiet most of the time. Whatever he was creating inside the cottage, as long as it came out soon, would meet his usual publication schedule of a book every few years.

In the summer of 1989, my uncle, the novelist Charles Newman, rented a cottage near the weekend home my parents owned on Cape Cod. Uncle Charlie, as I was still absurdly in the habit of calling him as an 18-year-old, was out of place on the Cape — he avoided the water and lacked a family to indulge at the ubiquitous drive-ins and miniature golf courses. The brand-new black Acura Legacy with gold trim that he had driven all the way from St. Louis, its trunk packed full of high-potency multivitamins and Mahler CDs, stood parked all summer in the cottage’s white, sandy driveway like a rebuke to the entire peninsula. I never went inside the cottage. My mother had instructed me to not even drive down the street when Charlie was working, which was always, and to never under any circumstances ask what he was working on. After the summer ended, though, we inferred that it had been productive. Charlie was sober, stable, and had been quiet most of the time. Whatever he was creating inside the cottage, as long as it came out soon, would meet his usual publication schedule of a book every few years.

At 51, Charlie was nearing the pinnacle of his strange but just-as-he-would-have-it career. Not that he cared about reputation, or so he claimed, but only a few years earlier he had produced a volume of essays, The Post-Modern Aura, which despite being called “Hegelian” for its “daunting” prose and “exquisitely complex argument,” had been something of a sensation for a work of literary criticism, garnering euphoric reviews (“Brilliant,” “Scathing,” “Brilliant,” “Relentless,” “Brilliant,” “Brilliant,” “Brilliant”) in one newspaper or magazine after another. His previous novel, White Jazz, had been a New York Times book of the year and bestseller. Outside of writing, though still trapped in the emasculating, brain-deadening torture chamber of academia, he was in the best position he had ever known to maximize his output, having somehow, despite a record of adversarial relations with previous employers, secured a plummy professorship at Washington University, home to one of the best writing programs in the country, where he taught little and no longer had to edit for a living. (For years Charlie had been the editor of TriQuarterly, where, as a junior professor at Northwestern in his 20s, he accomplished the dream of every small-time lit mag editor in the world: turning a no-name campus rag into a vehicle for Nabokov, Borges, and Calvino.)

At 51, Charlie was nearing the pinnacle of his strange but just-as-he-would-have-it career. Not that he cared about reputation, or so he claimed, but only a few years earlier he had produced a volume of essays, The Post-Modern Aura, which despite being called “Hegelian” for its “daunting” prose and “exquisitely complex argument,” had been something of a sensation for a work of literary criticism, garnering euphoric reviews (“Brilliant,” “Scathing,” “Brilliant,” “Relentless,” “Brilliant,” “Brilliant,” “Brilliant”) in one newspaper or magazine after another. His previous novel, White Jazz, had been a New York Times book of the year and bestseller. Outside of writing, though still trapped in the emasculating, brain-deadening torture chamber of academia, he was in the best position he had ever known to maximize his output, having somehow, despite a record of adversarial relations with previous employers, secured a plummy professorship at Washington University, home to one of the best writing programs in the country, where he taught little and no longer had to edit for a living. (For years Charlie had been the editor of TriQuarterly, where, as a junior professor at Northwestern in his 20s, he accomplished the dream of every small-time lit mag editor in the world: turning a no-name campus rag into a vehicle for Nabokov, Borges, and Calvino.)

Most important, his writing powers were at their peak, at least in theory. Looking back at his prose from that period, you can see that “the long line” he’d pursued for so long had finally come to him, whether because he’d found the right form to pursue it in (“Every writer has to find their form,” Charlie would often say, his own journey having taken him from the personal essay to cultural criticism and both minimalist and maximalist fiction, though I suspected that his real métier was The Angry Letter: the denunciatory, bridge-burning screed), because he’d stopped drinking, or something more mysterious.

Don’t ask what your uncle is writing about — but I was 18 at the time, the age at which being told “Don’t do something” makes it impossible to do anything but. One day, a few months after that summer on the Cape, while visiting Charlie in St. Louis, I waited until he went to campus and tiptoed upstairs to his office.

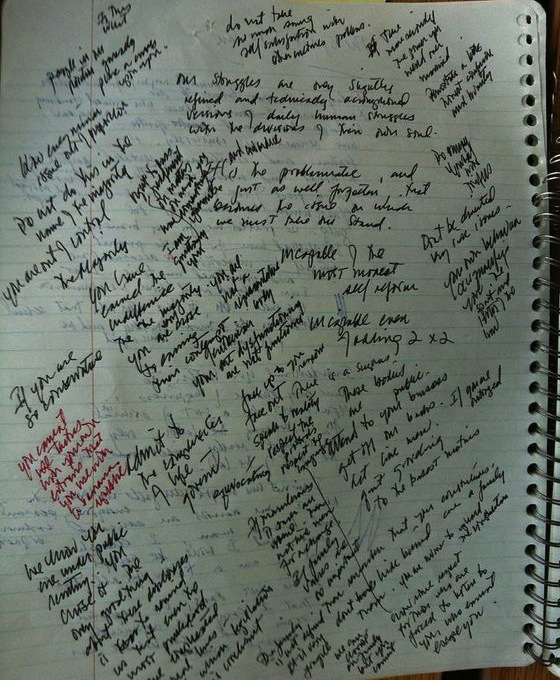

Charlie’s goal when he started each day was to come up with one or two, possibly three sentences he liked, and to get there he wrote out his drafts by hand, then sent the pages to an assistant, who returned them typewritten on plain white sheets, which Charlie then cut into slivers, isolating individual sentences before reinserting them with Scotch tape in the handwritten notebooks, or tacking them to a wall. Those tacked-up sentence slivers were before me now, along with dozens if not hundreds of pink and yellow note cards scrawled with riffs, phrases, lists, and snatches of dialogue. The book, in other words, was in front of my face — no drawers had to be opened, no papers rifled through. The office itself was surprisingly clean and uncluttered, aside from 50 or so briarwood pipes and an astonishing number of overdue library books.

I stayed in the office until the Acura pulled in the driveway an hour or so later, by which time I still had no idea what the book was about. Charlie’s kinetic shorthand was often indecipherable even to assistants who had worked with him for years, and as for the sentences that had been typed out, they were typically fragments (“army of deserters,” “mad for sanity”) or mystical pronouncements such as “History has a way of happening a little later than you think” or “In Russia you always have to buy the horse twice.” Sometimes they contained no more than a single word. (“Deungulate.”)

However, the question also has to be asked: Even if I had found some synopsis for the novel-in-progress, what difference would it have made? Charlie’s books tended to thwart summary. How, for example, would you distill the plot of White Jazz? (“Sandy, a young man who works for an information technology company, sleeps around”?) How would you describe the subject of The Post-Modern Aura: art? Literature? History? Or simply the abjectness of the human condition? Even sympathetic readers often found themselves struggling to say what Charlie’s books were about. (Paul West, attempting to describe the novel The Promisekeeper in a 1968 review for The Times, called it “not so much a story as an exhibition, not so much a prophecy stunt as a stunted process, not so much a black comedy as a kaleidoscopic psychodrama.”)

2.

Over the next several years, Charlie continued to work on his mysterious book in St. Louis and New York (where he lived when he wasn’t teaching), as well as various parts of Europe, Russia, and the U.S. He and my parents frequently traveled together; all of us sat with him in restaurants and walked through museums in places like Santa Fe, Chicago, and Kansas City and did everything possible to avoid asking — to not even think about — the question we most wanted to ask.

But then a surprising thing happened: Charlie began to talk about the book. I can’t exactly remember when it became clear that he was not going to lunge across the table if we brought it up, but some part of him softened, something opened up, and if you weren’t inelegant about it (“The worst kind of mistake[is] not a moral but an aesthetical one,” Charlie would write, not jokingly) you could extract a few details — which of course weren’t always that enlightening.

“It’s the great un-American novel,” he would say in a cheerful mood, or “It’s a novel for people who hate novels, a novel pretending to be a memoir that’s really a history” — or something like that. Sometimes he would go on at length, easefully sketching out major characters, including the most important character of all, “Cannonia,” the invented country in which the book was set. Sometimes he would simply say “it’s indescribable — nothing like it has ever been written.” Then there’d be nothing but one of Charlie’s “special repertoire of silences” hovering about the table, until eventually the conversation moved on.

“It’s the great un-American novel,” he would say in a cheerful mood, or “It’s a novel for people who hate novels, a novel pretending to be a memoir that’s really a history” — or something like that. Sometimes he would go on at length, easefully sketching out major characters, including the most important character of all, “Cannonia,” the invented country in which the book was set. Sometimes he would simply say “it’s indescribable — nothing like it has ever been written.” Then there’d be nothing but one of Charlie’s “special repertoire of silences” hovering about the table, until eventually the conversation moved on.

The openness could have been reassuring, a sign that Charlie was on top of his book and didn’t fear talking it away. The more he spoke, though, the more I worried, in part because the book he was describing sounded not just indescribable but unwriteable. First, there was its premise: Charlie said he was going to write the history of a place which did not exist but wherein virtually everything described — characters, events, locales — was real, drawn from actual sources. That alone explained why the book was taking so long: Charlie had obviously gotten bogged down in research. (A grant proposal I later discovered listed his primary texts as “obscure diaries, self-serving memoirs, justifiably forgotten novels, carping correspondence, partisan social and diplomatic histories, black folktales and bright feuilletons.”) But it wasn’t the only reason to be nervous; there was also Charlie’s intention to somehow merge his fake-but-real history with a spy thriller, a cold war novel of suspense. Was such a book even possible? Wasn’t a spy thriller supposed to be brisk and plotted, and history (even pseudo-history) ruminative and disjointed? How would you blend the two genres? And then there was Charlie’s insistence that the book, despite its writerly ambitions, would somehow be “accessible and commercially viable,” containing not one but “several” movies. This seemed least fathomable of all — the most uncompromising writer ever, bowing to conventional taste? Altogether the project seemed impossible, even for Charlie, who once vowed to “write books that no one else could write” and who would have rather changed careers than give up experimenting.

3.

About eight years later and a month or so after Charlie’s death in 2006, I went back to his office — not the one I’d trespassed in in St. Louis but the one in New York, which was in a gloomily black-windowed high-rise on West 61st Street called The Alfred. The space was as Charlie had left it before he died, and at the bottom of a closet, underneath an assortment of dirty blankets, Italian suits, and hunting clothes, I found an old television still murmuring, its picture tube faintly aglow. It had been five months since Charlie was there, but I had the sense that the inflamed set had been attempting its manic, muffled communication even longer. The clothes inside the closet were as hot as if they’d just been ironed.

Unlike the office I had been in 15 years earlier, this one was squalid, cluttered with foldable picnic tables, overstuffed vinyl chairs, and still-running air purifiers blackened by pipe tobacco. The couches were stained and burnt. Every level surface was covered with manuscript pages, newsletters from financial “gurus,” and advertisements for eternal life potions. The entire Central European history and literature sections of the Washington University library seemed to be on hand, plus hundreds of books on espionage and psychoanalysis. I made a list of titles near Charlie’s desk: Freud and Cocaine, Were-Wolf and Vampire in Romania, Escape from the CIA, A Lycanthropy Reader, Mind Food and Smart Pills.

Back in the 1990s, when Charlie moved into the Alfred, the feature of his apartment he had been proudest of was a custom-built series of cubbyholes spanning one entire wall, which he would use to organize the Cannonia manuscript. Like his openness when discussing the book, the shelves had a reassuring aspect — after all, they were finite (you could see where they ended) and therefore so must be the book!

But the actual filing system I discovered after Charlie’s death bespoke madness, the cubbyholes having been filled with household items that had nothing to do with Cannonia. Instead, the manuscript was stored in dozens of sealed Federal Express boxes which had apparently been sent back and forth from New York to St. Louis and vice versa — draft after draft after draft after draft, so many it was impossible to tell which was most recent. The boxes, many of them having been taped shut years ago and never reopened, piled up under the plastic picnic tables. Also in the apartment were hundreds of sealed manila envelopes containing those cut-out, typed-up sentences — “Angry hope is what drives the world,” “He had brains but not too many,” “Women fight only to kill” — which it appeared Charlie had also been mailing, one tiny sliver per envelope, whether to an assistant or himself wasn’t clear.

Charlie had several helpers at The Alfred — unofficially, the doormen, who knew he only left the building to go to the Greek diner two blocks away, and to call the diner’s manager when he did to make sure he arrived. There was also a young woman he had hired to fix his virus-flooded Gateway and provide data entry — in the office I found her flyer with its number circled, the services it advertised including not only computer repair but martial arts instruction and guitar lessons. I met her a few times after Charlie’s death and we talked about the book, which she claimed Charlie had finally finished. “I know because we wrote it together,” she said. “He thought up the ideas for the scenes and I wrote them.” But she never showed me the completed, final manuscript, and a few weeks after we met she stopped returning calls.

4.

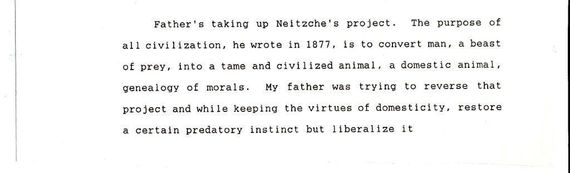

Here is the story of Charlie’s book, I think. In the 1980s Charlie wrote a novel, the story of Felix, a bankrupt “breaker of crazy dogs and vicious horses,” and the Professor, a certain Viennese psychoanalyst who brings Felix neurotic animals and theories of the mind. This modestly-sized, thoroughly old-fashioned book “split the middle,” to use one of Charlie’s favorite phrases, between fantasy and autobiography — Charlie, of course, being neither a Central European aristocrat living on an abandoned royal hunting preserve (as Felix is), nor an acquaintance of Freud. He was, however, a one-time breeder of hunting dogs who owned a kennel and horse farm in one of the most isolated parts of Appalachia, where, like Felix, he imported exotic plant specimens and found a way to escape the academic-literary-intellectual world he loathed. Losing the farm, as he did in the mid-1980s (to inflation, as he described it — inflation also being the scourge of several of Charlie’s books, it is worth noting), was surely the novel’s impetus.

“I wanted to write a long novel about the farm,” he once told an interviewer, “but the farm was so hurtful to me in many ways, not only economically but in terms of the loss of beloved animals,” as well as what he called a “nineteenth-century” existence.” So he wrote a short novel instead, one that was a throwback as much as the farm. In many ways it is a response — positive and hopeful, for all the unhappiness it apparently came out of — to the wrenching blankness of White Jazz and The Post-Modern Aura, works that depict spiritual suffering (“a vast cultural sadness,” in Charlie’s words) in an age of multiple, overlapping determinisms. For if nothing else, Felix lives in a world where his own agency matters, and where meaningful connections — with his wife, his animals, the Professor, and perhaps above all the land he lives on — are possible.

Charlie could have published the story of Felix and the Professor in the early ’90s, roughly maintaining his schedule of a book every few years. But one of Charlie’s idiosyncrasies as a writer is that he would often write something, then put it aside, and years or even decades later find some unexpected way to combine it with other, different material. In the case of the book inspired by the farm, he decided to hold off in favor of incorporating it within a massively enlarged work to be harvested from the book’s fantastical setting — Cannonia. Now instead of one book there would be roughly nine, divided into three volumes, all to be published at the same time. (“No dribbling out,” he growled when I asked if he would consider publishing even a little of the material before he’d reached the end.)

Having thus re-envisioned his tidy coastal steamer as a three-decker battleship, Charlie set out to write an introduction of suitable vastness, providing centuries of background and introducing characters who would not reappear for thousands of pages. The nature of the project all but required him to take this world-building approach. The story itself could wait. Characters could get away with announcing themselves in the grandest possible manner, then vanish. Charlie’s passion for history and obscure primary sources could be indulged. It was all part of the excitement, the buildup, the setting of an appropriate tone.

Ten years later, Charlie was still writing the overture to his symphony. And not surprisingly, the time it was taking, plus the future amount of work he could surely see coming, not to mention the embarrassment of attempting such a behemoth, weighed on him visibly. A lifelong alcoholic who frequently stunned even the people who knew him best with his capacity for self-destruction and recovery, Charlie had curtailed his drinking in the 1980s through Alcoholics Anonymous and sheer white-knuckle effort, then lost control in the ’90s, undoubtedly in part due to the stress of Cannonia. Toward the end of the decade his nervous system began to break down, and he spent much of the following years in the hospital, where doctors at first thought he might have suffered a stroke or the onset of Parkinson’s. Intermittently unable to speak or walk, he put aside the trilogy for long stretches, struggled with depression, and when the wherewithal to write eventually returned, started a pair of new books instead, a history of American education and a long essay on terrorism. He also became estranged from family, saw his fourth and final marriage end (“Why do people fear dying alone and unloved?” he had already written at this point, glimpsing the future. “What difference does it make?”) and reduced his teaching to the point where he was scarcely seen on campus.

During these years Charlie seemed to answer conflictingly every time he was asked if the book was done. In 1998, it was three-quarters finished, in 2005, only two-thirds, while in 2002 it was complete. His assistant in St. Louis believed he might never stop rearranging the table of contents and inserting new pages, and in fact he never did.

5.

The first time I read a draft of In Partial Disgrace, Charlie was still alive, and reading it all but put me into despair, not only for Charlie but at the idea any writer could suffer the kind of delusion he’d suffered so long. Page after page after page, there was nothing but setting or background. Cannonia, “our ineffable tragi-comic protagonist, superior to tragedy,” a country that is “effectively all border” and usually covered on maps by the compass sign or coat-of-arms, its natives standing guard over a mystical redoubt where Europe’s vanished species, such as the Tarpan horse and auroch, still thrive, was certainly a magical-sounding place, but it appeared one in which things only happened, usually in the distant past—there was virtually no present, no now. In many passages Charlie’s powers as a writer, rather than being at their peak, seemed to have dribbled out of him after all. How could an author who once wrote this:

“In front, as usual, were the graduate students, dressed in the russet, olive, beige and black of phlegmatic earnestness. Further back, spilling into the aisles, sprawled the gaudier, paisleyed and striped undergraduates, umbrellas and rainwear steaming in piles at their feet. In the balcony he could make out what must have been a visiting high school band class, restless, jaunty; girls smoothing tartan skirts about their knees, in serried rows assembled. How he loved girls who wore high socks.” (The Five-Thousandth Baritone)

and this:

“So it was that the Sandman had an inkling of Modern Revenge. The lost self, a bit of sugar in the gas tank. To the degree he had forgotten, he was.” (White Jazz)

think seriously of publishing turds like “the muse is mostly merciless” and “misconstruction makes the morning coffee”? I was confused also because so much of the novel Charlie had talked about for so long seemed missing. Where was Freud? Where was Pavlov? Where were the battle scenes, and where were the spooks? After 400 pages I put it down — obviously I held only a fragment of the overall work to come, and there was nothing to do but wait.

Then, after Charlie died, I found the story of Felix and the Professor, a novel that was alive in its language, arresting in its ideas, and humanly engaging in its depiction of a friendship between two painfully isolated men. Like the television at the bottom of the closet, it pulsed with warmth. The question was how to disentomb it.

6.

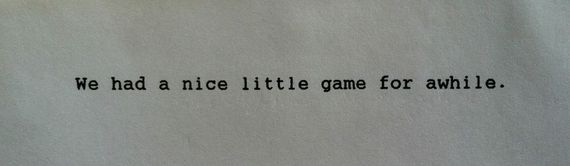

I had been struggling to edit the novel — I could feel its shape but was groping for a center of gravity — when one day while sorting through Charlie’s papers, one of those envelopes containing a single cut-out sentence dropped from a yellowed folder and landed at my feet. I picked it up, pulled out the scrap of paper and read, if not exactly a synopsis of the book, a clear answer to the Professor’s question.

It was as if a series of flat, flickering images had suddenly merged into a three-dimensional figure and the figure had eyes that were looking into your own. The idea of “reversing” civilization was the book’s continuous line, though it dipped in and out of view, submerged at times by other lines. Previous books of Charlie’s contained it as well: “Hey, let’s get some dinner. Be civilized,” says one of the unpleasant characters in White Jazz, a cruelly cartooned airhead feminist. “What’s civilized about dinner?” the Charlie-esque protagonist retorts.

I was elated, of course, but also chilled. In Partial Disgrace is positive and hopeful in that Felix is fully alive (unlike his weak, scolding counterpart, Dr. Freud), but what makes him so is his wrathful rejection of society, especially the institution of family.

Essentially the book portrays a man who, in true Nietzschean fashion, wills his way past cant and technobabble and bad art and the disorienting spirals of inflation — all the bad actors of our time — to becoming historical, to claiming a place in time. However, in spite of this, or perhaps because of it, at the end of the book one of Felix’s key connections fails: the Professor commits one of those unforgivable aesthetic violations, and in his fury Felix is unmasked as a malevolent demon who wields art (like Charlie, Felix is writing a book he can’t finish) as a weapon, to “be brought to bear against the cult of family values and civil society in general.” If you remember the end of Notes from Underground, you know the feeling this brings. It is the most wretched and exhilarating ending to any book I have ever read.

7.

And then last summer, while organizing Charlie’s papers, I came across another important document: a letter from an assistant doing research for him in the New York Public Library. The date: 1983, earlier than any other indication I’d seen of when Charlie started working on In Partial Disgrace. Did he ever envision the book would take 30 years? Had he known, if he had been able, what would he have changed? Nothing, I suspect. If you as a writer were given the choice — family, sanity and health on one hand, and The Book on the other — which would you pick? Especially if that book, or even just part of it, turned out exactly the way you wanted: perfect, dark, and unique.

[Editor’s Note: This essay appears, in slightly different form, as the Editor’s Note to In Partial Disgrace, published this month by Dalkey Archive Press]