The first line of Suzanne Scanlon’s novel, Promising Young Women, is a knockout — “Ever since I heard Don Reakes say that the beauty contestant deserved to be raped by Mike Tyson, I wanted him dead,” — and from there the book only continues to deliver jabs of trenchant insight and fine-tuned language. The novel proceeds in a series of fragmented portraits that follow the young Lizzie, actress and wandering, suicidal soul, through a series of psychiatric institutionalizations, most significantly in the SS Roger, a ward for super-sensitives. Promising Young Women is a writer’s novel in its preoccupation with language and its many facets, and it’s also a performer’s novel in its concern for the performative, and especially in the (re)performance of texts it’s aligned with, like Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar. Curtis White likens the experience of reading Promising Young Women to riding a wave: “The reader is driven before the story like something driven before a wave. And that is a deeply pleasurable feeling.” And Kate Zambreno, in her 2012 Year in Reading, called the book “a series of fragmented, poetic portraits…marked by Suzanne’s really gorgeous, wry, erudite voice.” Suzanne and I corresponded via email in a conversation that touched on the ways narratives are codified to create meaning, the liberating experience of reading and working with David Foster Wallace, and art as “the impossible trajectory of hope.”

The first line of Suzanne Scanlon’s novel, Promising Young Women, is a knockout — “Ever since I heard Don Reakes say that the beauty contestant deserved to be raped by Mike Tyson, I wanted him dead,” — and from there the book only continues to deliver jabs of trenchant insight and fine-tuned language. The novel proceeds in a series of fragmented portraits that follow the young Lizzie, actress and wandering, suicidal soul, through a series of psychiatric institutionalizations, most significantly in the SS Roger, a ward for super-sensitives. Promising Young Women is a writer’s novel in its preoccupation with language and its many facets, and it’s also a performer’s novel in its concern for the performative, and especially in the (re)performance of texts it’s aligned with, like Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar. Curtis White likens the experience of reading Promising Young Women to riding a wave: “The reader is driven before the story like something driven before a wave. And that is a deeply pleasurable feeling.” And Kate Zambreno, in her 2012 Year in Reading, called the book “a series of fragmented, poetic portraits…marked by Suzanne’s really gorgeous, wry, erudite voice.” Suzanne and I corresponded via email in a conversation that touched on the ways narratives are codified to create meaning, the liberating experience of reading and working with David Foster Wallace, and art as “the impossible trajectory of hope.”

The Millions: The epigraph for Promising Young Women contains three quotes; I’d like to focus on the first two, by Clarice Lispector and Ariana Reines, that allude to the inevitable interdependency of literature and life. Lispector’s quote, “She wanted to explain that that’s what her life was like, but not knowing what she meant by ‘that’s what it’s like’ or ‘her life’ she didn’t answer,” implicates language and all of its inadequacies (an idea you return to throughout the book) while Ariana Reines’s asks if a book can sufficiently construct other worlds and transport the reader between these worlds: “Can a book carry you into the world you have to pretend doesn’t exist most of the time, can a book carry you back out into what first made you alive.” With this in mind, how do literature and life intermingle for you as a writer, and also in what way does this interaction speak to your vision for Promising Young Women?

Suzanne Scanlon: I’m not exaggerating when I say that much of my identity has been founded or invented or re-created on the books I’ve read. I’ve always read that way — for instructions on how to live, as Flaubert put it. There have been times in my life when the worlds/ideas offered within a book — Virginia Woolf or Marguerite Duras or Shakespeare or Erica Jong — were immensely comforting to me — a balm, a relief from the limitation of the worlds/ideas most present in so-called real life. I guess I’m also very influenced by and interested in writing that, as Ben Lerner put it in an interview, recently, “collapses the distinction between art and life.” I wanted the referenced literature to be central to the life of Lizzie, she has collapsed this distinction in her mind (for better or worse), such that while she’s lying in the quiet room, having been administered a shot of Thorazine, she’s thinking about Virginia Woolf. That’s funny to me, and problematic and true; it might be as dangerous to her as it is her salvation.

TM: I’d love to hear you talk about the performative aspects of writing as an actress and theater critic — how does writing character in fiction compare to taking on a role as an actress? What inspiration does your writing draw from theater and acting?

SS: As a theater student, I was very early educated on a voracious reading of plays, of going to the theater — part of why I went to college in New York. Theater has been a passion of mine for as long as I can remember and I think the world of it is great training for a writer. I recall very well the excitement of my first exposure to Beckett, Ionesco, Chekhov, Caryl Churchill, Wallace Shawn, Karen Finley, to name only a few playwrights — it was simply magic to discover these writers. And in a contemporary sense, I think some of the most interesting writing these days is happening for the theater (Young Jean Lee, Annie Baker, my dear friend David Adjmi, to name a few); there’s an attention to language, to rhythm, and an openness to experimentation that isn’t always valued in (mainstream) fiction. There’s also a playfulness, an awareness of the futility/absurdity of language, the artifice — but with a persistent sense of hope, which is taken for granted in the theater. Erik Ehn once said that the theater is about “the impossible trajectory of hope” and I never forgot that. I suppose that’s what I think all art should be.

TM: You touch on the power of spoken language in your story (or is it an essay?), “How I Lost My Dictionary,” where the narrator is carjacked by a boy claiming he has a gun that he never reveals: “This is a stick-up. If you say something, does it make it true? If you call your finger a gun, does it make you powerful? Do the words matter?” In Promising Young Women, it seems that the psychiatrist’s diagnoses function in the same way — if Roger says Lizzie is sicker than he thought then this becomes truth. In what way do words matter, especially in the ways they define identities and catalyze interactions? In what way is life a performance?

SS: Thank you for reading that piece! Yes, that’s long been a concern and, at times, obsession of mine. The way narratives get codified and repeated to create meaning. There was a time when this terrified me — the way that naming, labeling, delimits identity. As a parent, I see it anew: how a child may take to a label s/he is assigned (shy, smart, naughty, etc.) and then live up to it; the way families begin very early to assign, and repeat narratives (the lazy one, the difficult one, the responsible one). When Roger uses the term “Designated Patients” this speaks to the same idea — there is always a scapegoat, one to play the role — we like to limit identity and are less comfortable understanding the self as a fluid, multivalent thing. If we did accept that, we might see that we are all more alike than we could bear.

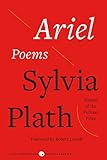

TM: Many reviews of Promising Young Women have remarked on the number of literary allusions folded into the relatively short novel — from Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar and Ariel, from Joyce’s “The Dead” and Ulysses,, from Tolstoy and Melville, too. You’ve also borrowed scenes and structural devices and integrated them into Promising Young Women, and specifically scenes from The Bell Jar. This strikes me as a form of acting, perhaps in the sense of adopting roles of other novels and acting them out within your own. It also seems like an intriguing, fresh take on allusion. Could you talk more about the literary ancestors and allusions and borrowing, and how these play into the novel for you?

TM: Many reviews of Promising Young Women have remarked on the number of literary allusions folded into the relatively short novel — from Sylvia Plath’s The Bell Jar and Ariel, from Joyce’s “The Dead” and Ulysses,, from Tolstoy and Melville, too. You’ve also borrowed scenes and structural devices and integrated them into Promising Young Women, and specifically scenes from The Bell Jar. This strikes me as a form of acting, perhaps in the sense of adopting roles of other novels and acting them out within your own. It also seems like an intriguing, fresh take on allusion. Could you talk more about the literary ancestors and allusions and borrowing, and how these play into the novel for you?

SS: Well, you know David Foster Wallace, who was my teacher at one point, does this throughout his work — he samples, alludes directly and indirectly — this is something I learned reading his work, and also through things he said. Reading him was mind-blowing: Wow, you can do that?! It was as if he gave me permission. I didn’t realize what fiction could be. I can say that about many writers, I guess, but for someone alive at the same time as I was — it felt huge. I remember reading “The Depressed Person” for example, and thinking, wow, so you can take that language and turn it around, make it do something else? Perform it, yes. I think his work is very performative, hysterically shifting, constantly referencing other works, other writers, while becoming his own.

Taking on the role of Plath, of course, using her words — well, it is easier in a novel than it is in real life. Just as Lizzie plays a woman who puts her head in the oven, I can play with Plath’s novel. I feel quite privileged, in fact, to be able to learn from Plath — to recognize her genius and the truth of her writing — and yet to have lived in a moment which has allowed me to approach it as one voice among many, one within a dialectic.

TM: The artist/writer Alexandre Singh recently laid out his own beliefs on the simultaneity of art-making by referencing Borges’s idea, that “every new artist causes the past to become deeper and richer. The past isn’t a dead, fixed place but one to which we’re constantly looking back to, discovering things, seeing things anew.” How do you envision this playing out within your writing? (Or do you?) To what extent do you see literature as enabling a dialogue with writers past and present (and future)?

SS: I do love the idea of the past as a shifting place, open to revision — and I like his idea that interviews are fictions! Yes, I feel like various dead writers are dear friends of mine — from Woolf to Plath to Duras to DFW — their lives and lessons and warnings and urgings are constantly informing my own, challenging my own. In this book, in writing in part about my mother’s death, I was both performing her life (which is supposedly fixed in the past, a space we are meant to leave behind) and her death. I was inventing a mother and then finding a way for her to die, to allow her to die. To move her to that place so that I might move there. I don’t know if that was conscious, but that’s how I see it now. For years I longed to speak to her, to get her advice, and I suppose a comfort in writing is being able to create her as much as I create a self.

TM: I was impressed by the verve and tone of the narrative voice — from the striking opening line, “Ever since I heard Don Reakes say that the beauty contestant deserved to be raped by Mike Tyson, I wanted him dead,” to aphorisms like, “There is a kind of loneliness that comes from being with people.” Much is said about the failure of communication, about the gaps between what is said and what is conveyed, about distances that cannot be bridged, about the utter failure to find the words, to convey messages. Very few writers who attempt this are able to communicate this breakdown so well. And yet this focus on the failure of language, its limitations, this occurs with a novel that, of course, relies on words. Would you speak more to the general weariness here, and also specifically the weariness towards language — the gaps and spaces?

SS: Well, yes, a general weariness. But I think the joy of writing is the feeling of reaching across or through those gaps. I love this essay by Susan Griffin where she states that her favorite moment in writing is “when the writing falls short.” I, too, find that exhilarating — that even at times the awareness of its limitation is comfort. This essay is in John D’Agata’s Next American Essay which also contains an essay by Annie Dillard, who is always working toward and around and through these gaps. I am not wearied when I read a line, a paragraph of hers or a line of DFW’s. I’m regularly thrilled by the movement toward or across that impossibility.

SS: Well, yes, a general weariness. But I think the joy of writing is the feeling of reaching across or through those gaps. I love this essay by Susan Griffin where she states that her favorite moment in writing is “when the writing falls short.” I, too, find that exhilarating — that even at times the awareness of its limitation is comfort. This essay is in John D’Agata’s Next American Essay which also contains an essay by Annie Dillard, who is always working toward and around and through these gaps. I am not wearied when I read a line, a paragraph of hers or a line of DFW’s. I’m regularly thrilled by the movement toward or across that impossibility.

I suppose there was a time when I felt like Lizzie the narrator — that it was a waste to even try. The older I get, the more grateful I feel to have the chance to try, to work within and against a tradition.

TM: One of the things that Lizzie says she learns on the S.S. Roger — the psychiatric ward for super sensitives where Lizzie is a patient — is that she’s a cipher: “I am an empty thing. A fragmented mutating subject.” This is central to Lizzie’s desire to try on identities through acting, and is echoed through the novel’s structure. The novel, too, is a fragmented mutating subject, told from various overlapping perspectives. I’m wondering if you could talk about the role of this structural system in Promising Young Women (or other structural systems you were/are drawn to). Did you consciously define the novel against the traditional male bildungsroman, with its phallic Freytag triangle and climax? Also, in this sense, are there other literary influences to this novel/your writing, that aren’t as conspicuous as, say, the Plath?

SS: No, it was not consciously defined against the bildungsroman, though I have been interested in what I read as female bildungsroman (like The Bell Jar or Kate Chopin’s The Awakening) and so in that way it’s a subversion. Many of my favorite books are fragmented in structure, resisting linear plot or redemption — perhaps especially work by women — Lydia Davis, Claudia Rankine in Don’t Let Me Be Lonely, Maggie Nelson, also The Lover, Jesus’ Son, Beloved, Brief Interviews with Hideous Men. I think that while revising certain sections of PYW I was rereading both The Bell Jar and Infinite Jest. These novels might seem dissimilar but both are kind of anti-coming of age stories and both, of course, contain descriptions of depression that feel inspired, true.

SS: No, it was not consciously defined against the bildungsroman, though I have been interested in what I read as female bildungsroman (like The Bell Jar or Kate Chopin’s The Awakening) and so in that way it’s a subversion. Many of my favorite books are fragmented in structure, resisting linear plot or redemption — perhaps especially work by women — Lydia Davis, Claudia Rankine in Don’t Let Me Be Lonely, Maggie Nelson, also The Lover, Jesus’ Son, Beloved, Brief Interviews with Hideous Men. I think that while revising certain sections of PYW I was rereading both The Bell Jar and Infinite Jest. These novels might seem dissimilar but both are kind of anti-coming of age stories and both, of course, contain descriptions of depression that feel inspired, true.

Also, my editor, Danielle Dutton, is a brilliant writer and reader and her vision for fiction and this book truly made these fragments cohere, essentially made this a book. There was a time when I saw these as a collection of linked stories, but she saw it as a novel.

TM: The phrases “Promising Young Women” and later, “Girls with Problems,” are such taglines for the ways that young, attractive, women are romanticized, and even exulted, for their dependencies, their great sadnesses and weaknesses, and who become projects for the men, like the psychiatrist and like the boyfriend, who want to or need to help. While the book exposes these clichés (much like it maligns Friends, whose laugh track and faux cheery camaraderie alienate Lizzie) does participation in this system become a self-fulfilling prophecy? How does one break from the loop, and where does Lizzie and the SS Roger fall into this?

SS: Honestly, I don’t know how to break from the loop, save from becoming an artist who is both outside and inside. I think getting older helps, too. It’s much easier not to be a young woman, though everywhere you go you’re told to feel bad about getting older. I think Lizzie wants to be part of this system as much as it wants her. I think it is a mutual dependency. I don’t see it in black and white terms; one can be exploited and helped all at once. But yes, self-fulfilling prophecies abound — as with the naming of someone ill or sick; she lives up to this idea of herself, which is an idea that she, on some level, wants/needs to believe at this point in her life. Part of her breakdown then becomes a gift, a breakthrough — a total embracing of an identity in order to exhaust it, perhaps, to wear it out. If that makes any sense.