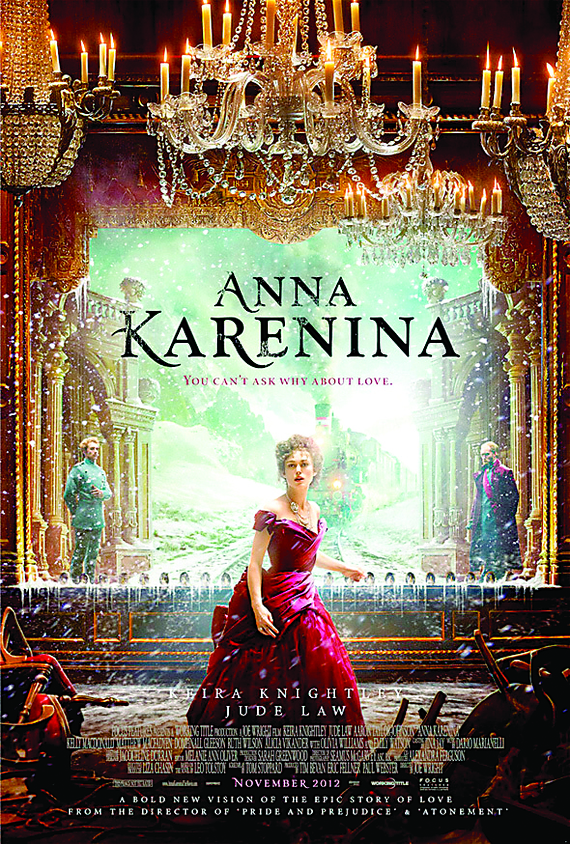

I’ve read Anna Karenina countless times, published articles, and dedicated two chapters in my book Understanding Tolstoy to the novel. So it is particularly exciting for me when an adaptation comes along that allows me to see the novel in a fresh light and even stirs me to tears over moments I thought I knew by heart. That happened to me a number of times while watching Joe Wright’s 2012 adaptation of the work. Which is why I was disappointed when the movie was nominated for Oscars in what amounts to the consolation prize categories, the ones having to do more with the style than the substance of the film: Cinematography, music (original score), costume design, and production design.

But then, I’m not surprised. Most criticisms of the movie have focused on the idea that it’s long on style, short on depth. Robert Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times writes, “This is a sumptuous film — extravagantly staged and photographed, perhaps too much so for its own good.” “Visually stunning, emotionally overwrought, beautifully acted, but not quite right,” claims Betsy Sharky of The Los Angeles Times. And yet, I would argue, that it is precisely by means of its stylistic prowess that Wright’s film captures the deeper truths about Tolstoy’s novel as successfully as any other adaptation I’ve seen.

But then, I’m not surprised. Most criticisms of the movie have focused on the idea that it’s long on style, short on depth. Robert Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times writes, “This is a sumptuous film — extravagantly staged and photographed, perhaps too much so for its own good.” “Visually stunning, emotionally overwrought, beautifully acted, but not quite right,” claims Betsy Sharky of The Los Angeles Times. And yet, I would argue, that it is precisely by means of its stylistic prowess that Wright’s film captures the deeper truths about Tolstoy’s novel as successfully as any other adaptation I’ve seen.

One of the most controversial aspects of the movie is the filming of the whole thing in a dilapidated theater. In making “the radical artistic choice to tell the story as if it were being enacted by players on a stage,” writes Lisa Schwartzbaum of Entertainment Weekly.com, “Wright falls passionately in love with his own fanciful artifices.”

Maybe, but he also gets at one of the novel’s central ideas: that this is a spectacle society concerned more about show than substance, with tragic consequences.

Two thirds of the way through the novel Anna goes to the opera. By this point, she’s deep into her affair with the juicy cavalry officer Vronsky and has left her husband Karenin, who refuses to give her a divorce, making it impossible for Anna to remarry legitimately. A woman without social standing, Anna is the talk of the town, and, apparently, the main attraction at the opera that night. A woman sitting in the box next to her makes a scene after the woman’s husband exchanges a few polite words with Anna.

Here’s what Wright does with that moment: A hush comes over the theater and all eyes turn from the stage to Anna, illuminated by a spotlight as she sits there in her light-colored gown of silk and velvet with a low-cut neck, in her glittering necklace, with expensive lace in her gorgeous, black hair — and utterly humiliated. That shot says it all: There sits the real diva of the night, the grand dame of Petersburg high society whose titillating story of adultery, self-destruction, and pariahdom those leering theater-goers thoroughly enjoy from behind their lorgnettes. That they, too, may be complicit in Anna’s sad tale is a possibility none of them bothers to consider.

But if Wright doesn’t demonize Anna, nor does he glamorize her, as is so often the case with filmmakers and readers alike. When Tolstoy first started working on the novel, he envisioned Anna as a kind of empty tramp, but the more he wrote, the more sympathetic he became to her plight. Still, at no point does he absolve her of moral responsibility for her own decisions, as some readers are too apt to do. Anna is a tragic figure, not merely because she is an emotionally deprived woman in a loveless marriage surrounded by empty hypocrites. She is also a victim of her own her romantic illusions, of making, in Tolstoy’s words, “the eternal error people make in imagining that happiness is the realization of desires.” By giving herself over to the fantasy of complete liberation, Anna becomes a slave to her passions, a star in a tragic story partly of her own design. She is a stark illustration of Tolstoy’s belief that one of the central problems of modern social life isn’t just that we’re all playing roles on a stage, but that those roles often end up playing — and destroying — us.

Wright (and Stoppard) might have made a safer bet by focusing exclusively on the sexy Anna-Vronsky plot, as other movies have done, but they instinctively understood this to be counter to Tolstoy’s intention. Anna and her tragic story reflect the truth that broken families, ungrounded passions, and human isolation are central to the modern experience. It is against these realities that the autobiographical rural landowner Levin, with his questing spirit and commitment to higher ideals, must fight. He belongs to a minority in his time — as he would in ours, which is why his story is vitally important today. Levin strives for meaning that neither the social artifice, the reductive scientific world view, the moral relativism, nor the pseudo-religiosity of his era can provide. Dostoevsky called him one of those “Russian people who must have the truth, the truth alone, without the lies we unthinkingly accept.” The director’s choice to film the Levin scenes at his estate in the countryside in a realistic as opposed to a stage setting is actually quite brilliant in communicating the impression Tolstoy gives in the novel that Levin is one of the few characters in his world who is connected to something real and authentic.

Then there’s Karenin, whom Wright correctly senses is a lot more like Levin than most readers ever suspect, at least when it comes to his uncompromising belief in ideals and principles. Wright doesn’t reduce him to the mean-spirited, rational machine so many filmmakers have made him out to be. Karenin is a deeply principled man who is simply incapable of accessing or expressing his emotions. But they’re there, all right, and Jude Law makes us feel them. When Karenin is sitting alone at the front of the stage before the dimming flood lights, having just learned that Anna is pregnant with Vronsky’s child, he turns slightly towards his wife (and the viewers) and says, “Tell me what I did to deserve this.” That heartbreaking moment reveals all the depth of his confusion. Like everybody else in Tolstoy’s novel, he has been thrust into a tragic situation beyond his capacity to understand.

Do I think this is a perfect movie? No. Keira Knightley is a little too young-looking and too thin for Tolstoy’s voluptuous, 28 year-old Anna. The movie could have made the connection between Anna’s and Levin’s storylines even more explicit, as Tolstoy does when he has the two meet near the end. There are moments here and there where the acting doesn’t quite ring true, as in that scene when Vronsky reacts to the news that Anna is pregnant with his child. And maybe the British tabloids had a point when they wondered why Wright decided to turn the dark-haired Vronsky into a blond.

But to criticize is easy. To create is hard. And Wright has shown himself to be every inch the creator, not on the level of Tolstoy, of course, but certainly on the same emotional and philosophical wave length.

A literary adaptation, in my view, shouldn’t be an imitation, but an interpretation. And a good interpretation, as any literature teacher or literary critic knows, is one that doesn’t cover a book, but uncovers it. For me, Wright’s film did that. The power of this movie isn’t merely in the fact that the director has willfully re-shaped Tolstoy’s classic according to his own bold, wacky conceit, but that in his very stylistic quirkiness he has actually brought us surprisingly close to the philosophical vision of the original work. For that even the most dedicated Tolstoy aficionados can be grateful. The Academy should have looked a little bit deeper.