Building Stories, by the comics artist Chris Ware, comes in a large, flat box, roughly the size and shape of the boxes that contained those boardgames you used to play as a child, and which children everywhere have presumably now abandoned for digital diversions. I ordered it online, and because I wasn’t home when it arrived (and because the thing was never going to fit into my postbox) I had to put aside some time later that week to pick it up from a delivery depot about a mile and a half from where I live. When I got there, I rang a little bell at an unmanned hatch. A guy eventually appeared and asked for my name and address, then went away and came back with this large package, which I then signed for, took out to my car, lay across the back seat, and drove home. I say all of this by way of establishing that this is a sizable and intractably physical object, and that I had to endure some (admittedly minor) inconveniences to get to where I could sit down and spend time with it.

Building Stories, by the comics artist Chris Ware, comes in a large, flat box, roughly the size and shape of the boxes that contained those boardgames you used to play as a child, and which children everywhere have presumably now abandoned for digital diversions. I ordered it online, and because I wasn’t home when it arrived (and because the thing was never going to fit into my postbox) I had to put aside some time later that week to pick it up from a delivery depot about a mile and a half from where I live. When I got there, I rang a little bell at an unmanned hatch. A guy eventually appeared and asked for my name and address, then went away and came back with this large package, which I then signed for, took out to my car, lay across the back seat, and drove home. I say all of this by way of establishing that this is a sizable and intractably physical object, and that I had to endure some (admittedly minor) inconveniences to get to where I could sit down and spend time with it.

My point, I suppose, is that having to go a little out of your way might actually be the most appropriate way of arriving at Building Stories, a work of art whose quietly monolithic presence lies well beyond the central marketplace of contemporary literary culture. I call it a work of art, by the way, not in order to rhetorically elevate it, but rather to avoid having to call it a “book,” which is more or less exactly what it isn’t. Firstly, it’s a great big box, and then, once you’ve opened that, it’s a whole paper treasury of beautiful odds and ends – a series of small booklets and pamphlets, a couple of variously sized hardbound volumes, a massive and aggressively cumbersome broadsheet, a series of folded panels that opens out into a tetraptych – all of which is bound together by a clear plastic band. These things have to be removed and laid out, as though they were the contents of an aesthetic care-package, and they have to be appreciated before they can be read. So the first thing about Building Stories, the initial way in which it asserts itself, is that it feels like opening an unexpected gift.

But once you stop merely looking at it and begin reading it, the delight and sheer fun of its form – of the gift’s presentation – is revealed as a beautiful irony. Because although the content of the box is bright and surprising, full of remarkable nested pleasures, the content of the art itself (the content, as it were, of the box’s content) is something very different: full-color infographics of stoically-borne despair, sadness, and boredom. Building Stories is, essentially, a sprawling assemblage of cartoons about the inhabitants of a single building in Chicago. On the ground floor is the elderly landlady, and above her lives a youngish woman and her sullen, undermining husband, who once played guitar in a rock band, but who now works night shifts as a security guard. For the most part, though, Ware focuses on the life of an unnamed woman with one leg amputated at the knee who lives on the third floor. There seems to be no particular order in which the stories should be read – no one way in which the parts unite to form a whole – and so you glimpse this life at various points and at the various degrees of its loneliness. You pick up one booklet and she is in her twenties, living alone in her apartment with her cat, working as a florist; you pick up another and she is married to an architect (who looks very much like Chris Ware) and living in the suburbs with a young daughter; in another, she is just out of art school, working as an au pair with a wealthy couple and their son.

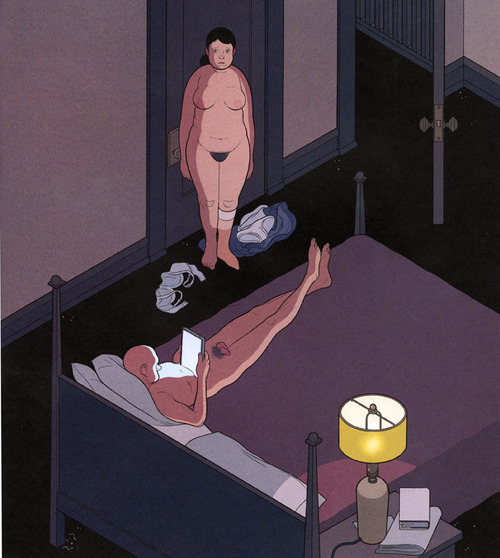

And yet despite this haphazardness, whereby the reader pieces this fractured graphic narrative together in whatever way comes to hand, there is always a forceful sense of the steady passage of time. We see the woman’s face change, her sadness seeming to settle into its structure; and, in Ware’s many unclothed depictions of her, we see the inevitable slump and spread of her body, her shoulders hunched under a private history of tolerable defeats. The only part of her that doesn’t grow old, that isn’t sliding along an illustrated continuum of decay, is the part that is already dead – her prosthetic left leg. In one of the most emotionally affecting panels, she stands in pear-shaped nakedness by the door of her bedroom, her clothes bunched on the floor around her. Her husband lies stretched out on their bed, also naked, his long legs crossed at the ankle, his slackly oblivious cock reclining away from her across his right thigh, his chest and face illuminated by the unreal glow of the iPad he is holding in his hands. The expression on her face is one of helpless misery, like a child prematurely exposed to adult disillusionments. It’s heartbreaking to look at everything that Ware somehow manages to imply in the simple lines of her face: her doubts about her husband’s desire for her and her own desire for him, her sudden dismay about the shape of her life, and of the body with which she is moving through it. It’s precisely the ordinariness of all this that is surprising; she is, in other words, not a nude, but – far more beautifully and movingly – a naked woman.

The passing of time, with its slow devastation of bodies and lives, is a major dimension of Building Stories. One of the comics focuses on the building’s elderly landlady; its entire front page is given over to a wordless scene in which she snoozes in her armchair by the television, sitting out what little time she has left, as a maid hoovers around her. Ware zooms in repeatedly on her left hand, a seized arthritic claw with its bulbous knuckles, resting on the arm of the chair. At one point a fly lands on the back of her hand without her noticing; it’s only when it moves to her face that she brushes it away, like a thought about the approach of death. Inside the comic, she thinks about the uneventful life she led, working as a shop assistant, trapped at home caring for a bedridden mother. A central double-page spread opens out into a diagram of the building’s stairwells, and as we move downward, reading from left to right, the process of aging is illustrated. First she is a little girl playing on the stairs, then a woman mopping it, then finally a frail and crotchety old lady rebuking her maid as she cleans the floor.

Ware has a way of making the most banal visual details unaccountably touching; in particular, I found the sight of the old lady’s hands removing the plastic wrap from a pre-prepared lunch plate (triangular sandwich, half a banana, two apple slices) desperately sad. Again, it’s the ordinariness of the image that is affecting. Like Philip Larkin, or the Joyce of Dubliners – a book with which Building Stories has a great deal in common – Ware has an extraordinary instinct for the empathic illumination of banality. He makes plain – beautifully and unsentimentally plain – the fact that nothing is more ordinary than to be lonely and despairing and dying. Perhaps this sounds depressing. It isn’t. Only bad art is depressing; good art, no matter what its subject, is exhilarating. Building Stories takes everyday sadness and makes something very beautiful of it, something powerfully human and true. That is a rare gift, and I’m very thankful to have received it.

Ware has a way of making the most banal visual details unaccountably touching; in particular, I found the sight of the old lady’s hands removing the plastic wrap from a pre-prepared lunch plate (triangular sandwich, half a banana, two apple slices) desperately sad. Again, it’s the ordinariness of the image that is affecting. Like Philip Larkin, or the Joyce of Dubliners – a book with which Building Stories has a great deal in common – Ware has an extraordinary instinct for the empathic illumination of banality. He makes plain – beautifully and unsentimentally plain – the fact that nothing is more ordinary than to be lonely and despairing and dying. Perhaps this sounds depressing. It isn’t. Only bad art is depressing; good art, no matter what its subject, is exhilarating. Building Stories takes everyday sadness and makes something very beautiful of it, something powerfully human and true. That is a rare gift, and I’m very thankful to have received it.