Here is what is magisterial about Leela Corman’s new graphic novel, Unterzakhn: it arrives with the force of artistic conviction, the unholy lovechild of Love and Rockets and Isaac Bashevis Singer. Corman, an author and illustrator, tells the tale of two sisters on the Lower East Side at the turn of the last century, her canvas crowded with fishmongers and fabric-sellers, and, as she adds to the mix, a loveless marriage, a dance cabaret/brothel and an illegal abortionist. Yet Corman’s story is economical: plucky twins Fanya and Esther, stark-nosed and smart-mouthed Jewesses, come of age in a place where choice is etched as sharply as Corman’s black-and-white lines. Fanya finds work too young in the apartment of a celibate abortionist, while Esther finds her way to the cabaret and tarnished stardom. Old Country pathos protrudes in the depiction of the twins’ likable father’s past. All the while, a deeper question thrums behind the catcalls, gossip, reproaches, survival strategies, and wit of Corman’s Lower East Side: does shared suffering alone create the tie that binds? And finally, the anger, love, and ultimate loyalty that lives between the sisters steals the show. It is a credit to Corman that you will not forget the outcome of these girls’ lives — a story simple and fabulistic, as in the best of Singer, with dark overtones that come from faithless characters in whom we can trust.

Here is what is magisterial about Leela Corman’s new graphic novel, Unterzakhn: it arrives with the force of artistic conviction, the unholy lovechild of Love and Rockets and Isaac Bashevis Singer. Corman, an author and illustrator, tells the tale of two sisters on the Lower East Side at the turn of the last century, her canvas crowded with fishmongers and fabric-sellers, and, as she adds to the mix, a loveless marriage, a dance cabaret/brothel and an illegal abortionist. Yet Corman’s story is economical: plucky twins Fanya and Esther, stark-nosed and smart-mouthed Jewesses, come of age in a place where choice is etched as sharply as Corman’s black-and-white lines. Fanya finds work too young in the apartment of a celibate abortionist, while Esther finds her way to the cabaret and tarnished stardom. Old Country pathos protrudes in the depiction of the twins’ likable father’s past. All the while, a deeper question thrums behind the catcalls, gossip, reproaches, survival strategies, and wit of Corman’s Lower East Side: does shared suffering alone create the tie that binds? And finally, the anger, love, and ultimate loyalty that lives between the sisters steals the show. It is a credit to Corman that you will not forget the outcome of these girls’ lives — a story simple and fabulistic, as in the best of Singer, with dark overtones that come from faithless characters in whom we can trust.

Edie Maidav: What extraordinary conjunction of forces inspired you to write Unterzakhn?

Leela Corman: What a great way to ask that hard-to-answer question of inspiration!

Well, the first thing that happened was kind of a weird conjunction in itself. I went to a Kim Deitch lecture at the West Side YMCA one evening in 2003. I went to day camp at this Y when I was little. The lecture was held in the same auditorium where we had to gather every morning to sing “The Other Day I Met A Bear” and, I kid you not, “Y.M.C.A.,” complete with hand gestures.

While waiting for the lecture to begin, Fanya suddenly appeared in a napkin doodle, with a pillow under her dress, looking into a mirror and saying Yuck! The lecture kind of took a while to begin, and more characters started to appear. By the end of the evening I knew that Fanya had a twin named Esther, that their mother owned a corset shop, and that their father was “Old Country” and didn’t talk much. I knew they lived on the Lower East Side, and that one became an abortionist/midwife, and the other a showgirl. That all came in one evening.

So, at that point, the ideas started percolating outwards, and I began to do a little research about that neighborhood. Actually, in some ways the idea started much earlier; I had a thought when I was still in art school to do a story about a Jewish showgirl in pre-war Poland. But I could never get that idea to walk. I think I was sick of pre-war Poland, and WWII in general. Some of the very raw material for her ended up evolving into Esther/Delilah.

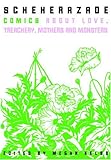

Anyway, once I started researching all of the relevant subject matter — the history of contraception, the history of the Lower East Side, vaudeville — the story began to coalesce a little more. Megan Kelso asked me to contribute to her Scheherazade anthology, so I used it as an opportunity to work with those characters for the first time. And then after that there were years of research and note-taking. I tend to have the characters first, and then work outwards from them.

Anyway, once I started researching all of the relevant subject matter — the history of contraception, the history of the Lower East Side, vaudeville — the story began to coalesce a little more. Megan Kelso asked me to contribute to her Scheherazade anthology, so I used it as an opportunity to work with those characters for the first time. And then after that there were years of research and note-taking. I tend to have the characters first, and then work outwards from them.

Oh, and I also wanted to add, I wanted to talk about the time when women did not have choices in reproduction. The consequences of not having a choice are gruesome. Slowly the book evolved much more towards the “fun” stuff — Esther’s story — but I did keep much of that original intention in there.

EM: One aspect that makes Unterzakhn so striking is your seeming fondness for the way complex characters slip out of any single moral judgment the author might rest upon them. You manage to make life messy, impossible, and lovable and yet do so with a clearly bifurcated structural axis. What sort of works, in any medium, have drawn you in the way in which their creators withhold judgment upon equivalently complex characters?

LC: My favorite works, and the ones that have had the greatest influence on me, do exactly what you describe. I dislike stories that treat human beings too simply, although it is often necessary to have secondary or tertiary characters who serve only one or two functions. I read a lot of fiction, but none of it really influences my work, because novels are such a different medium. In a novel, there is so much inner life. And when I read, I am deep in the world of the book, and not even thinking about its structure. I’m like an ant playing on a great piece of architecture.

Creating a graphic novel is more like manipulating actors, except mine can’t argue and they don’t get paid. So the works that have had the most influence are usually film and really good episodic TV writing, which we are blessed to have a lot of right now. Certain other cartoonists are also a big influence; in fact, the Hernandez Brothers, and Gilbert Hernandez in particular, loom very large over me with this book. I feel like Gilbert Hernandez is a very explicit influence here.

Some other huge influences: Mad Men and Deadwood, two of the greatest things that have ever been on a screen of any size. I recently started re-watching Deadwood and I’m amazed at how much it influenced Unterzakhn. I originally saw it in 2006, before I really started working on it, and I guess I’d forgotten, or never really understood, how much it seeped into everything I did. That is a classic example of characters who would be easy to judge — most of them have blood on their hands. But as the long arc of the story progresses, it becomes more difficult for the viewer to do so, and even more difficult — if not impossible — for the characters to judge one another, or hold their lives apart from those they deem below them or of lesser morals. With the exception, of course, of the characters who are created for that purpose.

In the case of Mad Men, the characters are more modern, and are in a setting where they (mostly) aren’t going to do things that are explicitly horrible, with a few exceptions. But the things they do are more subtle, their motivations not simple, and generally driven by the deep and often unquestioned fears and needs we all experience.

The work of Pedro Almodóvar has long been a touchstone for me. But the single biggest influence on me while working on this book is a film called Head-On (Gegen Die Wand), by Fatih Akin. I watch it a few times a year, and always learn something new from it. It has been my school of storytelling. He never gives you what you think you want for the characters. He gives the story what it demands. This allegiance to the story above all else makes the movie breathtaking and almost unique, at least for an American audience. I could go on and on about that movie!

The work of Pedro Almodóvar has long been a touchstone for me. But the single biggest influence on me while working on this book is a film called Head-On (Gegen Die Wand), by Fatih Akin. I watch it a few times a year, and always learn something new from it. It has been my school of storytelling. He never gives you what you think you want for the characters. He gives the story what it demands. This allegiance to the story above all else makes the movie breathtaking and almost unique, at least for an American audience. I could go on and on about that movie!

Every film I watch, I dissect; I can’t help it. Another brilliant storyteller who I like to think has some influence, though I think I’m really flattering myself to think so, is the Iranian-Kurdish director Bahman Ghobadi, who may possibly be the greatest filmmaker on the planet. So maybe influence is the wrong word — I just love his work and try to take it in very deeply. The same can be said for Akin and Almodóvar.

I have to say, also, that Busby Berkeley and vaudeville/Depression-era movies are a big influence on my aesthetic, and probably on the way I write dialogue. I honestly don’t know where half my dialogue came from; the characters have smart mouths of their very own.

EM: The smart mouths make more complex what otherwise might be a more straightforward moral symmetry, the kind of black-and-white that punches a reader in the best way. And graphically, too, the boldness of your drawings of the Lower East Side connote such a stark world regarding a community’s idea of decency and stigma and the singular tipping points between these two realms. Interestingly, when you draw the Old World, you use more shades of gray. This nuance seems to heighten the vast distance — temporal, geographic, moral — between the damning past of the Old World and the hungry present of the New.

Back in the Old World, Isaac, the girls’ father, makes a series of scarring choices, never to be rewarded for his bravery, ethics, or passion, and I find your restraint, both in terms of construction of his character and how you draw his environ, so moving. Were you considering a different way of drawing when you depicted Isaac’s backstory?

LC: I didn’t intentionally use a different tonal landscape for those two parts of the story. I had originally planned to have Isaac’s part of the story printed in a different color. But ultimately I decided against that, because I realized it would look too much like a sepia-toned flashback. I think it happened organically. Isaac’s homeland is mostly farms and small towns; it’s muddy, hilly, forested. New York city was sooty, crowded, and shadowed. Life took place in close quarters, indoors and out. Of course I’m projecting my imagination back in time to two places I’ve never been. But my family did come from Poland and I did grow up in Manhattan, so it’s not that hard to extrapolate. And, you know, research. Research plus imagination takes you where you want to go.

There is no moral symmetry in real life. I was worried once I’d finished the book that I’d accidentally created a moral fable, but I hope that the characters are too complex for that.