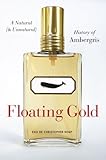

Leave it to a molecular biologist to so lyrically detail the scent of hyper-condensed sperm whale poop. Christopher Kemp, in his first nonfiction book, Floating Gold: A Natural (& Unnatural) History of Ambergris, writes

It has taken decades to become the substance I am holding in my hand. In its complex odor is reflected every squall and every cold gray wave. I am smelling months of tidal movement and equatorial heat—the unseen molecular degradation of folded compounds slowly evolving and changing shape beneath its resinous surface. A year of rain. A decade spent swirling around a distant and sinuous gyre. A dozen Antarctic circuits.

Ambergris.

People have used ambergris (‘gray amber,’ French) for a long time — Moctezuma added it to his tobacco, Casanova to his chocolate mousse, England’s King Charles II to his eggs; 17th-century French physicians used it to cure rabies, Florida’s American Indians as an antidote for fish poison, and today, companies like Chanel and Guerlain as fixative in their most expensive perfumes.

People have used ambergris (‘gray amber,’ French) for a long time — Moctezuma added it to his tobacco, Casanova to his chocolate mousse, England’s King Charles II to his eggs; 17th-century French physicians used it to cure rabies, Florida’s American Indians as an antidote for fish poison, and today, companies like Chanel and Guerlain as fixative in their most expensive perfumes.

But exactly what it is or how it’s produced has a long history of misunderstandings. Before Nantucket whalemen hacked it out of sperm whales’ intestines in the early 18th century, Europeans were mystified by the fragrant nubbins randomly washing ashore. To name a few mistaken sources, among a long list compiled by Kemp, it was at one time or another thought to be the fruit of underwater trees, extra-terrestrial rocks, or fossilized tree sap; the Chinese called it “dragon’s spittle.”

Still, we can’t seem to get it exactly right. Just last month Canadian researchers found that a compound from balsam fir trees can effectively replace ambergris in perfumes. Following the discovery were a number misinformed headlines: “Breakthroughs in Science: ‘Whale Barf’ Is No Longer Needed to Make High-End Perfume” (The Atlantic, 6 April 2012); “Your Perfume may soon be free of Whale Vomit” (New York Daily News, 9 April 2012).

But as the Tasmanian fisherman Louis Smith could have told you — who, Kemp uncovered, in 1891 wormed his way down the bowels of a beached sperm whale to find a 162-pound hunk of ambergris — it definitely is not vomit; it definitely comes out the other end.

Kemp, an American working at New Zealand’s Otago University, became interested in ambergris when a small boulder of tallow washed ashore and, mistaken for ambergris, was sliced up into assumingly small fortunes by the local Kiwis. At $20 per gram, that meant the authentic 32-pounder Lorelee Wright found on an Australian beach in 2006 was worth about $300,000.

After finding disparagingly little literature on ambergris — aside from a handful of passages in old books — Kemp set out to write something like the first Concise History of Ambergris, chapter-to-chapter playing cetologist, maritime historian, and, after he sets out to find his own piece, lottery junkie.

In his treasure hunt, we follow him from distant, windswept coastlines (my favorite, the “biscuit-colored apron of sand” notched in the little wet Stewart Island off the southern coast of South Island, New Zealand) to dusty storage rooms in the bowels of museums.

Along the way Kemp parses centuries of one of the more fanciful natural histories, illuminating a not-so-distant past of scientists flailing around to understand the natural world. Right around the time the first American paper on ambergris was published (1720s, by Zabdiel Boylston, Cotton Mather’s physician), appeared papers on “The Height of a Human Body, between Morning and Night,” and “Some Observations Made in an Ostrich, Dissected by Order of Sir Hans Sloane, Bart.”

It’s hard not to fall in love with ambergris, or the concept of ambergris as the unknowable embodiment of the sea, along with Kemp. Here is a solid lump of whale feces, weathered down—oxidized by salt water, degraded by sunlight, and eroded by waves — from the tarry mass to something that smells, depending on the piece and whom you’re talking to, like musk, violets, fresh-hewn wood, tobacco, dirt, Brazil nut, fern-copse, damp woods, new-mown hay, seaweed in the sun, the wood of old churches, or pretty much any other sweet-but-earthy scent. Borne in whale guts to be crushed and dabbed on the wrists and necks of the elite.

In following Kemp to where spume and salt and storms dash the seaboard — and all the Moby Dick references—I can’t help but think of Ishmael, ruminations on sea and land blowing through the pages. Kemp’s treks along the fringes of distant islands, his ponderous observations of thunderheads — “enormous black columns that tower thousands of feet into the sky” — washing over remote beaches, strike the same chords as Melville’s Ishmael in the crow’s nest, lulled by “the blending cadence of waves with thought, that at last [a young sailor] loses his identity”.

In following Kemp to where spume and salt and storms dash the seaboard — and all the Moby Dick references—I can’t help but think of Ishmael, ruminations on sea and land blowing through the pages. Kemp’s treks along the fringes of distant islands, his ponderous observations of thunderheads — “enormous black columns that tower thousands of feet into the sky” — washing over remote beaches, strike the same chords as Melville’s Ishmael in the crow’s nest, lulled by “the blending cadence of waves with thought, that at last [a young sailor] loses his identity”.

There’s that same ebbing away of self as Kemp tries to find a nubbin that looks and smells both singular and like everything, clear up a history that gets increasingly obscure, pry answers from an almost-legal network of tight-lipped ambergris hunters roaming the beaches with their ambergris-sniffing dogs, and pin down scent-descriptions from lyrical French perfumers until he finally loses track of what he was looking for in the first place, only to find something else.

At some point, he begins to trust ambergris’s mystery. No matter how many pieces he smells and touches, it is as unknowable and varying as the sea. It is, as he noted in his description of its smell, a history of sea itself.