Recently I watched a TED talk by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie called “The danger of a single story.” It was about what happens when a group of people comes to be known by a narrative that posits them as “one thing, only one thing, over and over again.”

Adichie’s talk was situated squarely within the intellectual framework of postcolonial studies — the study of power relationships between colonizing nations and colonized peoples. She followed the line of critique made by Edward Said in his 1978 classic Orientalism in arguing that the more powerful impose, in Said’s words, “crude, essentialized caricatures” on the less powerful.

Adichie gave several examples of the single story in action: The single story of Africa as a place of catastrophe; the single story of Mexicans as “abject immigrants;” the single story of poor people “as [nothing] else but poor.”

“Power is the ability not just to tell the story of another person,” Adichie said, “but to make it the definitive story of that person.”

Adichie argued that single stories dispossess people of their humanity, spread mistruths and half-truths, and mark arbitrary divisions in the human tribe. “I’ve always felt that it is impossible to engage properly with a place or a person without engaging with all of the stories of that place and that person,” she said. “The consequence of the single story is this: It robs people of dignity. It makes our recognition of our equal humanity difficult. It emphasizes how we are different rather than how we are similar.”

Adichie is a captivating speaker. Her TED talk was infused with a level of detail and description that marked her as the talented storyteller she is, and which compelled me to watch her 18-minute talk once, and then again right afterwards. Both times I was mesmerized by the fierce humanity of her words, even as I acknowledged to myself that as a white, well-educated American male who’s been largely free to craft his own life story, it’s hard for me to understand the full weight of the point she’s making.

It did occur to me, though, that there is another kind of single story — very different from the single stories that Adichie talked about — that I do have experience with. These are the single stories that develop within intimate relationships. Unlike the narratives that dominate colonized peoples, this version of the single story creates both challenges and opportunities for the people subjected to them.

My wife, Caroline, and I have two boys — Jay, who will be three at the end of May, and Wally, who just turned nine months. Like all parents, we are tantamount to a colonial power in their lives. We define the moral world in which they operate. We dictate terms of value. We command them physically. We situate them within single stories.

As we tell it, Jay is our spirited son — stubborn, demanding, relentless — and Wally is our contented son — happy, calm, even-keeled. These narratives took root within weeks of their respective births. They are reinforced in family lore (brief as it is) when we recall how Jay screamed through an entire wedding reception when he was four months old, or we remember how Wally, on the very first day he was alive, patiently tried and tried again until he’d learned how to nurse. These narratives become ironclad when, as I’ve written about on my blog Growing Sideways, my wife and I create our own little availability cascade: One of us might be wrong but how could we both be wrong together?

All parents tell single stories about their kids and all kids wish they didn’t. Single stories are the principle reason that, eventually, kids become so eager to leave home — they want to escape the simple narratives told about them since they were born, to jar their parents into recognizing that they’re no longer (and maybe never were) the person they were made out to be when they were eight years old.

I went off to college trailed by the single story that I was a jerk, particularly to my brothers and sister. At the time that story felt inaccurate and hegemonic in all the ways that Adichie says that single stories can be. Sure, when I was six I’d peed on my sister, and over the years I’d committed various small-time atrocities against my younger brother. But I’d changed, and no one had seemed to notice!

The single stories told in families can be tyrannical. But they can also be motivational. In my heart I knew there was some truth to the single story my family told about me. To this day I still work hard to disprove it. When my three siblings and I get together I take pains not to dominate the conversation, and to be extra diplomatic, and to avoid wanton acts of older sibling cruelty that even to this day flash reflexively in my imagination. So single stories are useful when they make us aware of our flaws and prompt us towards reform.

Single stories don’t have to be negative stories, at least as they’re told in families. The single story my wife and I tell about our youngest son, Wally, paints him as cheerful and delightful. At some point he may find it tiresome to have to fulfill this story anew everyday of his life; he may want to show us (and himself) that he’s capable of moodiness and cynicism, and exists to do more than gratify us with his pleasant aura. But later in life, if he ever finds himself stuck in an unhappy place, maybe the single story we told about him when he was a kid will help him get unstuck — maybe it will remind him that he was once joyful and could be again.

Families themselves are wrapped in single stories. I know a father in Philadelphia who plays the cello and whose son, at age three, strums the guitar. Their family’s story is a story of music. I know another family who’s single story turns heavily on loss. And another whose story is built around political activism. And another whose story is told in the tableau of Ivy League decals affixed to the rear window of their car. These families, like all families, are more complex than their single stories. But at the same time, single stories perform an important function their family life, just as single stories perform an important function in the lives of all families: They remind family members of who they are, where they’ve come from, what they value.

Adichie talked about the importance of overcoming the single stories that cleave one group of people from another. In the context of the single stories that are told in families, though, I think the challenge is different: It’s not to overcome the single stories family members tell about each other, but rather to find a way to live within them — to accept, for example, that it’s possible for your parents to love you completely even if they don’t understand you entirely.

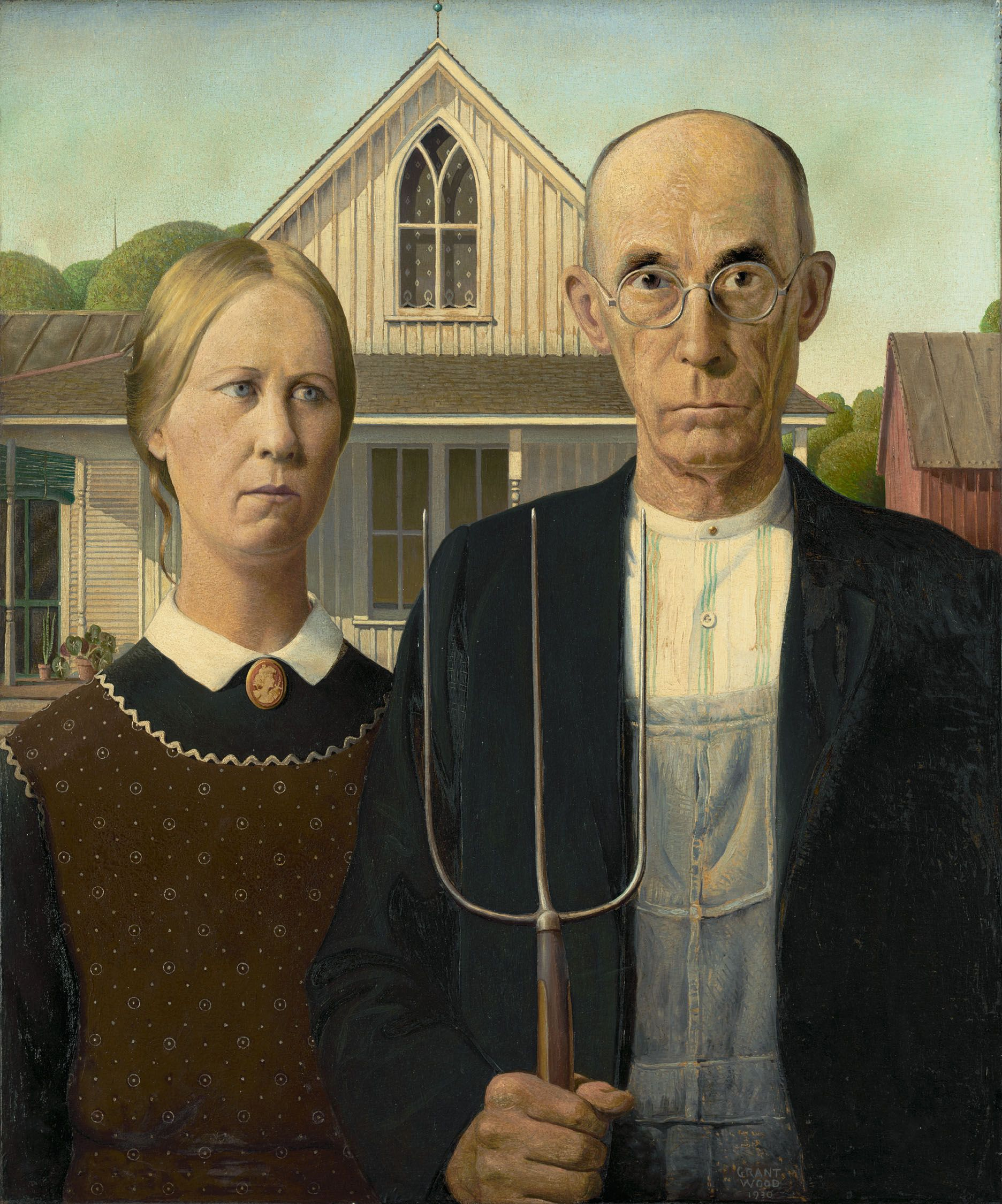

Image Credit: Wikipedia