|

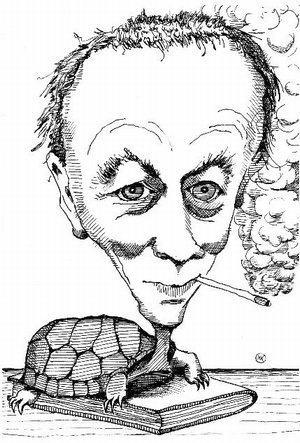

| A “sick old turtle” named Michel Houellebecq appears in Michel Houellebecq’s new novel, The Map and the Territory. Drawing by Bill Morris |

Few living writers have generated as much snark as Michel Houellebecq. Of all the rivers of bile that this dyspeptic bad boy of French letters has inspired, here is my absolute favorite sentence: “Like Haruki Murakami – in some ways his gentler (and far more gifted) Japanese counterpart – Houellebecq writes about the sulky crises of middle-aged male protagonists confronting existential superfluity while dealing with the destabilizing presence of alternately willing and withholding nubiles.”

Anyone who can keep a straight face while writing such a sentence – especially the bit about the destabilizing influence of alternately willing and withholding nubiles – is a writer you simply cannot ignore. So meet Rob Horning, who wrote the above for the on-line magazine The New Inquiry, in his review of a new book called Anti-Matter: Michel Houellebecq and Depressive Realism by Ben Jeffery. Horning gives a full inventory of what he finds offensive about Houellebecq’s fiction: its self-loathing, misanthropy, pessimism, cynicism, and hopelessness in the face of a life that is pointless and only made moreso by the hollow seductions of sex and consumer capitalism. “Houellebecq’s indiscriminate cynicism is not especially hard to get a handle on,” Horning writes. “He seems to operate on the assumption that the more mercilessly pessimistic or debasing an observation, the more titillatingly truthful readers will take it to be. He yearns to sound transgressive but more often than not comes across as petty and self-parodic.”

Horning bases this verdict largely on three of Houellebecq’s fictional gloomfests, The Elementary Particles (1998), Platform (2002), and The Possibility of an Island (2006). That’s a shame, because since then Houellebecq has published two books – a collection of correspondence with Bernard-Henri Levy called Public Enemies, and a new novel called The Map and the Territory – that reveal something Horning would likely find impossible to believe.

Horning bases this verdict largely on three of Houellebecq’s fictional gloomfests, The Elementary Particles (1998), Platform (2002), and The Possibility of an Island (2006). That’s a shame, because since then Houellebecq has published two books – a collection of correspondence with Bernard-Henri Levy called Public Enemies, and a new novel called The Map and the Territory – that reveal something Horning would likely find impossible to believe.

Namely: Michel Houellebecq may be a petty misanthrope and an average prose stylist, but he can also be drop-dead funny.

Here he is writing to his pen pal BHL in Public Enemies: “We are both rather contemptible individuals…basically I’m just a redneck, an unremarkable author with no style…a nihilist, reactionary, cynic, racist, shameless misogynist.” After pleading guilty as charged, Houellebecq points out that nihilists have feelings too: “The fact remains that I am uncomfortable and helpless in the face of outright hostility. Every time I did one of those famous Google searches, I had the same feeling as, when suffering from a particularly painful bout of eczema, I end up scratching myself until I bleed… In the end I stopped counting my enemies although, in spite of my doctor’s repeated advice, I still haven’t given up scratching.”

Granted, this isn’t exactly thigh-slapping material, but the Gallic wit is undeniable, as is the refreshingly gentle air of self-deprecation. These virtues are the centerpiece of The Map and the Territory, Houellebecq’s least violent and most tender novel, winner of France’s prestigious Prix Goncourt.

The book opens with a contemporary French artist named Jed Martin struggling to finish a painting he calls Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons Dividing Up the Art Market. Here’s Houellebecq’s take on the art world’s two reigning superstars: Koons had the slippery appearance of “a Chevrolet convertible salesman,” while “Hirst was basically easy to capture: you could make him brutal, cynical in an ‘I shit on you from the top of my pile of cash’ kind of way; you could also make him a rebel artist (but rich all the same) pursuing an anguished work on death…” This deft lampoon of the art world is marred by those random italics, a pointless stylistic tic that will recur, maddeningly, on every page.

The novel’s brashest and best gag is the introduction of a character named Michel Houellebecq, the famous French writer, who Jed enlists to write the catalog copy for his break-out exhibition, a series of altered photographs of Michelin road maps that give the novel its title. The author describes this Houellebecq character as “a sick old turtle,” a “tortured wreck,” and “a loner with strong misanthropic tendencies: it was rare for him even to say a word to his dog.”

The novel is most alive when we’re in the presence of Houellebecq, who loathes his native France so much that he has moved into a “banal” bungalow on the west coast of Ireland, where he putters around amid unpacked boxes, fretting, not getting much writing done. When Jed visits him there, a spark ignites between the two and the story begins to sing. Jed confesses that he expected the novelist to drink more than he does, and Houllebecq pounces on this opportunity to unload on some of his eczema-inducing enemies: “You know, it’s the journalists who’ve given me the reputation for being a drunk; what’s curious is that none of them ever realized that if I was drinking a lot in their presence, it was simply in order to put up with them. How could you bear to have a conversation with a twat like Jean-Paul Marsouin without being almost shit-faced? How could you meet someone who works for Marianne or Le Parisien libere without wanting to throw up on the spot?”

This has the ring of dark truth and it’s fun to read and I don’t doubt that it was fun to write. Unfortunately, there’s entirely too little of it, and the fun comes to an abrupt end when Houellebecq returns to France, buys the rural house he grew up in, and gets brutally murdered there.

There are only two nubiles in the book, both of the willing persuasion and both doomed to disappear without a trace, a fate common to many of Houellebecq’s characters. Much more interesting is the presence of a middle-aged woman named Helene, who is attractive, sexy, and happily married to Jasselin, the lead police investigator in the Houellebecq murder case. But this is an author who can’t stand prosperity. Soon after shocking us with a grisly murder and introducing us to this intriguing married couple, Houellebecq wanders off on a wheezing disquisition on the history, temperament, and health complications of their bichon dog (“the introduction of the Bolognese bichon to the court of Francois I came as a present from the duke of Ferrara…”). Such disregard for the reader goes beyond cynical; it’s vicious. And it has all the poetry of a Wikipedia entry. In fact, after weathering charges that he’d copied entire passages of the novel from the online encyclopedia, Houellebecq has added an acknowledgement in the American edition, thanking Wikipedia for being a “source of inspiration.”

Houellebecq has been compared, not unfairly, to everyone from Camus to Celine, William S. Burroughs, and Charles Manson. If I read him correctly, his lack of artistry is a conscious indictment of artistry, of prettiness, of writers bowing to readers who yearn for such cheap niceties as fluent prose, shapely narratives, and three-dimensional characters. Such things are both beneath Houellebecq’s contempt and beyond his powers, which is lucky for him. His stance means he’s free to demean something he’s incapable of producing. Nifty.

Which is not to say this is a wholly bad book. It’s full of clunky writing, but it has a few interesting ideas and engaging moments, some actual suspense, and a delightfully twisted sense of humor. That’s not nothing. And any writer who can call himself a “sick old turtle” and serve us his own severed head – well, that’s a writer you simply cannot ignore.