Click here to read about “Post-40 Bloomers,” a new monthly feature at The Millions.

1.

In considering why it took Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa until the age of 58 to begin work in earnest on his one and only novel, the luminous masterpiece Il Gattopardo, or The Leopard, Julian Barnes wrote:

In considering why it took Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa until the age of 58 to begin work in earnest on his one and only novel, the luminous masterpiece Il Gattopardo, or The Leopard, Julian Barnes wrote:

Lampedusa was afflicted with several handicaps (not so much to being a writer, but to being thrustful enough to dream of, and then achieve, publication): extreme shyness; enough money never to need take a job [he was a prince]; plus a sense that, as a Sicilian aristocrat, he came from an exhausted, irrelevant culture. There were other factors too, including a major nervous breakdown in his 20s, and a domineering mother.

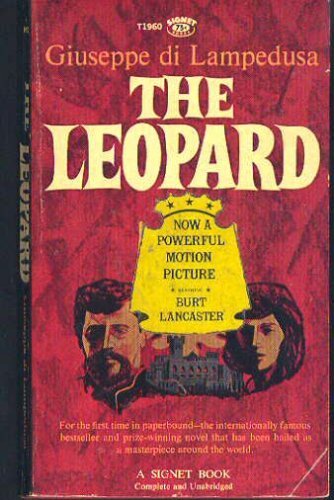

The roots of such unthrustfulness notwithstanding, one laments whatever convergence of factors precluded Lampedusa from a more prolific literary career. I first fell in love with Il Gattopardo via Luchino Visconti’s sumptuous film version (I’d seen it three times in fact, before reading Lampedusa’s original). It is unusual for me to read a book after seeing the film adaptation, but I was aware that some had criticized Visconti for staying, believe it or not, too close to the novel. I was thus eager to read it, and it has become, like the film, among my very favorites.

One indisputable factor that deprived us of more opportunities to luxuriate in Lampedusa’s gifts was a diagnosis of lung cancer in the spring of 1957, at age 60. The diagnosis came just a few months after he finished the novel. He had two publisher rejections already in hand, a third would arrive weeks before he died in July of that year. The author note of the Pantheon edition goes as far as to say that this third rejection came from an Italian editor who told him that his novel was ”unpublishable”—that Lampedusa, in other words, died with that declaration stamped upon his late-blooming artistic soul.

2.

One wonders just how shaped Lampedusa was by his exhausted, irrelevant culture, as he in fact lived a life highly atypical of a Sicilian of his era: influenced by his mother’s cosmopolitan bent, he was educated in Rome, read Latin and Greek, spoke German and French, and (almost unheard of at that time) eventually studied English. He served briefly as a lieutenant in the army during World War I and was imprisoned in a POW camp in Hungary. After the war, he traveled throughout northern Italy and Europe, and while visiting his uncle in England — of whose literature and culture he became (scandalously, for a Sicilian) enamored—he met Alexandra “Licy” Wolff Stomersee, a Latvian aristocrat and intellectual who studied psychoanalysis. The couple wed at Riga in 1932, in the Orthodox Church—another shocking departure from Sicilian cultural tradition—but eventually they lived apart, after his mother (domineering, yes, although some accounts additionally deem her “eccentric” and “open-minded”) forced her only son to choose between the two women. Licy was apparently no match for Signora Beatrice.

He spent the late years of the Second World War near the coastal town of Capo d’Orlando in Messina, with his mother and cousins, where he also reunited with his wife. After his mother died in 1946, Giuseppe and Licy returned to Palermo, where Lampedusa lived out his mature years, doing very little, strictly speaking: according to Barnes (whose source is David Gilmour’s biography, The Last Leopard), “on a typical day, he might first visit the bookshop and cakeshop, then sit reading in a cafe for hours, return home for tea and buns, and perhaps go out to the film club in the evening.” While most accounts confirm Lampedusa’s extreme taciturnity—a most “shut in” personality, someone you “met but did not know”—it was during these years that he began meeting regularly with a group of young intellectuals to discuss French and English literature.

3.

What more can I say that has not been said about this beautiful novel? In 2008, for The Leopard’s 50th anniversary—for yes, obviously and thankfully, it was eventually published, in 1958, the year after Lampedusa’s death—Rachel Donadio wrote a wonderful essay for The New York Times which I recommend and refer you to for your basic plot and historical context. Donadio also describes an event that year at NYU at which Lanza Tomasi, a younger cousin whom Lampedusa adopted as a son (presumably the autobiographical seed for the character Tancredi Falconeri, beloved nephew to our main character, il gattopardo himself, Don Fabrizio Prince of Salina) spoke of class divisions in the novel—essentially two classes, nobility and peasantry—as “unredeemable.” And yet, Lanza said, like all great novels, The Leopard transcends such boundaries. Reading it, “no one believes he’s the lower class,” Lanza said. The “miracle” Lampedusa produced in this novel is that “everyone believes he’s the prince.”

Everyone, indeed—even this Korean American woman living in New York City circa 2012. One’s love for Il Gattopardo is nothing if not a love for Don Fabrizio, a lusty middle-aged nobleman, the last of his kind at a time of social and geopolitical upheaval, with a passion for mathematics and astronomy, a soft spot for beauty and charisma, and a “certain energy with a tendency toward abstraction, a disposition to seek a shape for life from within himself and not what he could wrest from others.” He is a character with whom anyone who has found herself cultivating an independent soul, by choice or by necessity, feels an intimacy.

4.

And so, it is not just with interest, but with tender fidelity, that we follow Don Fabrizio’s affecting evolution from irritable dreamer to wistful relic. Early in the novel, as both political and familial disturbances encroach—the novel opens in 1860, as the war hero Garibaldi is gathering rebel volunteers to overthrow the Bourbon King for the cause of risorgimento, or the unification of Italy—Don Fabrizio considers “the endless little subterfuges he had to submit to, he the Leopard, who for years had swept away difficulties with a wave of his paw.” Without yet a vision for how to cope, how to move along with his times, he turns, as always, to the comfort, the “morphia,” of the skies:

The stars looked turbid and their rays scarcely penetrated the pall of sultry air. The soul of the Prince reached out toward them, toward the intangible, the unattainable, which gave joy without laying claim to anything in return; as many other times, he tried to imagine himself in those icy tracts, a pure intellect armed with a notebook for calculations: difficult calculations, but ones which would always work out. “They’re the only really genuine, the only really decent beings […] who worries about dowries for the Pleiades, a political career for Sirius, matrimonial joy for Vega?”

At this point, the Prince is primarily worried about domestic matters—the gradual but inevitable disintegration of his royal wealth into the hands of the new money classes. He is also worried about his sweet but unsophisticated daughter Concetta, who is in love with her dashing cousin Tancredi (Alain Delon in Visconti’s film version), whose fortune was squandered by the Prince’s brother-in-law and in whose future, political and social, the Prince sees great things. And he is worried for Tancredi’s impending engagement, around which the bulk of the novel revolves—to the enchanting Angelica (a young Claudia Cardinale, who else?), whose father, Don Calogero di Sadera, is exemplary of these crude rags-to-riches merchant classes in whose hands the future of Sicily, not to mention great sums of wealth, seem to lie.

But later, as the lovely Angelica and the Sedara family become fixtures in his life, as Tacredi’s future solidifies with the assurance of Sedara’s wealth, and as a unified Italy dominated by power (not nobility) materializes as a foregone conclusion, the Prince

found an odd admiration growing in him for Sedara’s qualities […] he began to realize the man’s rare intelligence. Many problems that had seemed insoluble to the Prince were resolved in a trice by Don Calogero […] he moved through the jungle of life with the confidence of an elephant which advances in a straight line, rooting up trees and trampling down lairs, without even noticing scratches of thorns and moans from the crushed.

The Prince is not exactly resigned, not exactly accepting; but neither is he self-deluding. He faces the coming reality with neither self-pity nor false optimism. He is il gattopardo—regal in the hot sun, dignified, elegant, weary, solitary. Wise to threats but unmoved, a creature of both survival and indifference. When the Secretary to the Prefecture entreats the Prince to represent Sicily in the new Senate, he responds with a lengthy speech, at once fiery and aching with melancholy, as if all the stages of grief have collapsed into one gorgeous oratorial moment, saying of himself, and of men like him,

We are old, Chevalley, very old. For more than twenty-five centuries we’ve been bearing the weight of a superb and heterogeneous civilization, all from outside, none made by ourselves, none that we could call our own. […] I don’t say that in complaint; it’s our fault.

Sleep, my dear Chevalley, sleep is what Sicilians want, and they will always hate anyone who tries to wake them […]

This violence of landscape, this cruelty of climate, this continual tension in everything, and these monuments, even, of the past, magnificent yet incomprehensible because not built by us and yet standing around like lovely mute ghosts; all those rulers who landed by main force from every direction, who were at once obeyed, soon detested, and always misunderstood, their only expressions works of art we couldn’t understand and taxes which we understood only too well and which they spent elsewhere: all these things have formed our character, which is thus conditioned by events outside our control as well as by a terrifying insularity of mind […]

I belong to an unfortunate generation, swung between the old world and the new, and I find myself ill at ease in both […] but I am without illusions; what would the Senate do with me, an inexperienced legislator who lacks the faculty of self-deception.

5.

Edward Said, writing about The Leopard in (his own late, last work) On Late Style: Music and Literature Against the Grain, characterized Don Fabrizio as

in effect the last Lampedusa, whose own cultivated melancholy, totally without self-pity, stands at the center of the novel, exiled from the continuing history of the 20th century, enacting a state of anachronistic lateness with a compelling authenticity and an unyielding ascetic principle that rules out sentimentality and nostalgia.

If I am reading Said correctly, he is associating lateness with both authenticity and asceticism, as well as a cultivated melancholia and exile. I prefer these associations to Barnes’s mere “unthrustfulness,” which Barnes (or perhaps the biographer Gilmour) in turn ties to exhaustion, irrelevance, reticence, nervousness, and submissiveness; for Said’s more appreciative assessment of “anachronistic lateness” applies not only to Lampedusa, but, it seems to me, to many of the late-life bloomers we’ve seen in this series; and to many of the artists I personally most admire.