1.

Book lovers love to watch two heavyweights slug it out. Bloodshed, though not necessary, is always welcome. Think of Paul Verlaine shooting his lover, Arthur Rimbaud, in the wrist. Think of Norman Mailer head-butting Gore Vidal for lumping Mailer with Henry Miller and Charles Manson as the misogynistic troika “3-M.” Or, less bloodily, think of Truman Capote hissing that Jack Kerouac’s writing was mere “typing.” Or Mary McCarthy claiming that every word Lillian Hellman wrote was a lie, including “and” and “the.” Or Richard Ford spitting on Colson Whitehead over his negative review of Ford’s A Multitude of Sins. Yes, we all love a good smackdown, regardless of the body fluids involved.

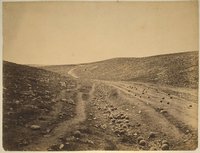

So naturally I was delighted that Errol Morris opens his absorbing new book, Believing Is Seeing (Observations On the Mysteries of Photography), with an uppercut to Susan Sontag’s jaw. (I should say unprotected jaw since Sontag, who died in 2004, will have a hard time delivering a counter-punch.) The uppercut by Morris (who is no relation) was triggered by a photograph – more accurately, by a pair of photographs – taken by the British photographer Roger Fenton during the Crimean War in 1855. One picture, devoid of people, shows a road curving between two hills and a ditch beside the road that’s littered with cannonballs. In the other picture, also devoid of people and taken from the same vantage point, the road is peppered with cannonballs; it is much more evocative of the horrors of war and is, rightly, the more famous picture. But which picture was taken first? For Morris, who urges readers to approach his sumptuously illustrated book as “a collection of mystery stories,” the answer is both ambiguous and hugely important. The reason Sontag gets Morris’ blood up is that she made the assumption in her last book, 2003’s Regarding the Pain of Others, that the cannonballs-on-the-road picture was taken second, thereby implying that Fenton posed the picture to heighten its impact.

So naturally I was delighted that Errol Morris opens his absorbing new book, Believing Is Seeing (Observations On the Mysteries of Photography), with an uppercut to Susan Sontag’s jaw. (I should say unprotected jaw since Sontag, who died in 2004, will have a hard time delivering a counter-punch.) The uppercut by Morris (who is no relation) was triggered by a photograph – more accurately, by a pair of photographs – taken by the British photographer Roger Fenton during the Crimean War in 1855. One picture, devoid of people, shows a road curving between two hills and a ditch beside the road that’s littered with cannonballs. In the other picture, also devoid of people and taken from the same vantage point, the road is peppered with cannonballs; it is much more evocative of the horrors of war and is, rightly, the more famous picture. But which picture was taken first? For Morris, who urges readers to approach his sumptuously illustrated book as “a collection of mystery stories,” the answer is both ambiguous and hugely important. The reason Sontag gets Morris’ blood up is that she made the assumption in her last book, 2003’s Regarding the Pain of Others, that the cannonballs-on-the-road picture was taken second, thereby implying that Fenton posed the picture to heighten its impact.

Here are the two sentences by Sontag that threw Morris into a swivet:

Here are the two sentences by Sontag that threw Morris into a swivet:

Not surprisingly, many of the canonical images of early war photography turn out to have been staged, or to have had their subjects tampered with. After reaching the much-shelled valley approaching Sebastopol in his horse-drawn darkroom, Fenton made two exposures from the same tripod position: in the first version of the celebrated photo he was to call “The Valley of the Shadow of Death” (despite the title, it was not across this landscape that the Light Brigade made its doomed charge), the cannonballs are thick on the ground to the left of the road, but before taking the second picture – the one that is always reproduced – he oversaw the scattering of cannonballs on the road itself.

This assumption prompts Morris to ask:

How did Sontag know the sequence of the photographs? …Presumably, there had to be some additional information that allowed the photographs to be ordered: before and after. If this is the basis for her claim that the second photograph was staged, shouldn’t she offer some evidence? …This raises a question that greatly interests me: why people accept claims of posing, fakery and alteration rather than looking at the data… Isn’t Sontag’s theory something like this?

These questions send Morris off on an exhaustive quest that is by turns bewitching, boring, frustrating, and fascinating. He operates under the belief, one I share, that if you dig up enough facts you will eventually approach something resembling truth. (Which is very different from saying that facts equal truth.) Morris travels to Sebastopol, he walks the road Fenton walked, he even locates a Crimean War-vintage cannonball to study how sunlight and shadow play on its surface. The remainder of the book is devoted to similar investigations into the ambiguity and meaning of photographs from Abu Ghraib, the Dust Bowl, Iwo Jima, Lebanon, and the battle of Gettysburg.

But it all spins around those two Fenton photographs. As Morris writes:

All of the central issues of photography that I address in this book of essays – questions of posing, photo fakery, reading the intention of the photographer from the image itself, questions about what a photograph means and how it relates to the world it photographs – are contained in these twin Fenton photographs.

As Morris’ investigations unfold, I sometimes found myself thinking that this guy has way too much time and money on his hands (including, presumably, some of that $500,000 grant he got from the MacArthur Foundation). But in the end, I wound up admiring Morris for his doggedness. If more prosecutors and police investigators were this rigorous, we would have far fewer innocent people on Death Row; and if more reporters and editors were this thorough, our news would be less tainted with factual errors and outright lies. In the end, Morris reminded me that all art springs from some kind of obsession. His obsessions lead him to some intriguing insights. The central one is stated in the book’s title:

What we see is not independent of our beliefs. Photos provide evidence, but no shortcut to reality. It is often said that seeing is believing. But we do not form our beliefs on the basis of what we see; rather, what we see is often determined by our beliefs. Believing is seeing, not the other way around.

It won’t spoil much to reveal that Morris’ painstaking investigation into the provenance of the Fenton photographs forces him to admit that Sontag was right all along – the picture with the cannonballs in the ditch was taken first, then someone scattered the cannonballs on the road for the second, more famous shot. (Presumably, someone had removed the cannonballs from the road before Fenton arrived on the scene and took his first shot.) What’s far more interesting than these facts is what Morris does with them. “The change in the photographs suggest that Fenton may have moved the cannonballs for aesthetic or other reasons,” Morris writes. “But we can never know for sure. And even if Sontag is right, namely, that Fenton moved the cannonballs to telegraph the horrors of war, what’s so bad about that? Why does moralizing about ‘posing’ take precedence – moral precedence – over moralizing about the carnage of war? Is purism of the photography police blinding them to the human tragedy the cannonballs represent?”

Saying that Susan Sontag belongs to “the photography police” is hitting below the belt. It was only after I finished reading Believing Is Seeing and went back to Sontag’s writings on photography that I began to see that Errol Morris, this dogged seeker of truth, had been less than fully truthful. But before we revisit Sontag, we need to drop in on Robert McNamara.

2.

My introduction to Errol Morris’ work was The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons From the Life of Robert S. McNamara, which won the Academy Award for the best documentary movie of 2003. (Lesson # 7: “Belief and seeing are both often wrong.”) I was drawn to the movie for reasons that were familial, political, and professional.

My introduction to Errol Morris’ work was The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons From the Life of Robert S. McNamara, which won the Academy Award for the best documentary movie of 2003. (Lesson # 7: “Belief and seeing are both often wrong.”) I was drawn to the movie for reasons that were familial, political, and professional.

First, the family connection. My father worked in the Ford Motor Company’s public relations department in the 1950s, when “Whiz Kid” Bob McNamara was rising toward the presidency of the company. My father saw McNamara frequently at the office but only occasionally at social gatherings because McNamara had little use for anything that distracted him from work. He lived in Ann Arbor, urbane home to the University of Michigan, far from the insular suburban enclaves favored by most Detroit auto executives. McNamara promoted small, fuel-efficient cars and auto safety – two farsighted propositions with zero profit potential. With his watered hair and rimless spectacles, with his radical ideas and iron faith in the power of numbers, McNamara was, according to my father and many others, a fish out of water in booming post-war Detroit.

One night my father came home from a cocktail party and told me a story I will never forget. Bob McNamara had showed up at the party, unexpectedly, and while most of the men gathered in one corner doing what Detroit car guys do – talking cars and sports while drinking the hard stuff – cold fish McNamara stood alone across the room. (Though my father didn’t say so, I’ve always pictured McNamara drinking a tall ginger ale.) After noticing that McNamara was soon surrounded by women, my father drifted over to eavesdrop. The women were listening, rapt, as McNamara recounted how he’d spent his summer vacation hiking in Utah. Few Detroit car guys in the ’50s had been to Utah, and I doubt that any of them had ever gone hiking. That story about how McNamara could mesmerize the ladies stayed with me in the coming years, after he went off to Washington and became Secretary of Defense and led us into the nightmare of the Vietnam War. That story forced me to remember that there was a complex human being – outdoorsman, raconteur, something of a ladies’ man – behind the icy mask.

Politically, I was opposed to the war while it was being fought, and I was determined not to take part in it. I had no desire to step on a land mine and get my legs blown off, of course, but on a deeper level I sensed, even as a teenager, that the Domino Theory was a load of horseshit. And to paraphrase our most eloquent draft resister, no Viet Cong ever called me honky. Vietnamese communists posed no threat to America, as I saw it, and Americans had no more business killing Vietnamese people than the French did. I was not going to go there to kill and/or be killed just because Lyndon Johnson, Robert McNamara, and Richard Nixon thought I should. The thing that saved me one-way bus fare to Canada was a lucky high number (#176) in the draft lottery in 1971, the year I turned 18.

When I went to see The Fog of War in 2003, my father’s story about that long-ago Detroit cocktail party was very much on my mind. I remember hoping that the movie would give us a three-dimensional McNamara – a man who had some visionary ideas, a man who could charm the ladies, a truly brilliant iconoclast – and not the cardboard monster so often served up by the media. Cardboard is not worth despising. To my delight, the movie delivers a complex human being. It shows McNamara pushing against the Detroit status quo for auto safety and small, fuel-efficient cars. It shows him fighting back tears when he recounts touring Arlington National Cemetery in November of 1963, trying to pick out a site for President John F. Kennedy’s grave. It shows that he was a dedicated civil servant who took a massive pay cut when he left Detroit for Washington, and that he was tortured by the consequences of his disastrous decisions as Secretary of Defense.

But Morris doesn’t let McNamara off the hook. For me the most unforgettable moment in the movie had nothing to do with the Vietnam War. It came when McNamara was describing his work crunching numbers – flight times, gallons of fuel, pounds of ordnance, abort ratios – for the fire-bombing raids on Japanese cities during the final months of the Second World War, under the command of bellicose Maj. Gen. Curtis LeMay. “In a single night we burned to death one hundred thousand Japanese civilians in Tokyo – men, women, and children,” McNamara says, blinking, as though still astonished by the memory. “LeMay said if we’d lost the war we would all have been prosecuted as war criminals. And I think he’s right! He, and I’d say I, were behaving as war criminals. LeMay recognized that what he was doing would be thought immoral, if his side had lost. But what makes it immoral if you lose, and not immoral if you win?”

Those words still stun me. The man had believed since 1945 that he was a war criminal – and yet he was capable of doing what he did in Vietnam!

Professionally, McNamara and I crossed paths as writers, in an oblique way, in early 1996. I had just sold my second novel, All Souls’ Day, the story of a former Navy Seal who took part in some dark missions along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, then settled in Bangkok after his discharge. Eventually he gets drawn back to Saigon during the C.I.A.-backed coup that culminated in the assassination of South Vietnam’s president, Ngo Dinh Diem, by his own troops on Nov. 2, 1963 (also known as All Souls’ Day, or the Day of the Dead). Three weeks later, President Kennedy was assassinated. My novel implied that this was the fork in the road, the moment when we should have cut our losses and gotten out of an unwinnable war.

Professionally, McNamara and I crossed paths as writers, in an oblique way, in early 1996. I had just sold my second novel, All Souls’ Day, the story of a former Navy Seal who took part in some dark missions along the Ho Chi Minh Trail, then settled in Bangkok after his discharge. Eventually he gets drawn back to Saigon during the C.I.A.-backed coup that culminated in the assassination of South Vietnam’s president, Ngo Dinh Diem, by his own troops on Nov. 2, 1963 (also known as All Souls’ Day, or the Day of the Dead). Three weeks later, President Kennedy was assassinated. My novel implied that this was the fork in the road, the moment when we should have cut our losses and gotten out of an unwinnable war.

A few weeks before I sold the novel (and a year before it appeared in bookstores), McNamara had published his memoir In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam. Most reviewers seized on McNamara’s tepid apology for the bloody fiasco he’d engineered – “We were wrong, terribly wrong” – but the book resonated with me for a very different reason. McNamara made what was, to me, another stunning admission: “I believe we could and should have withdrawn from Vietnam either in late 1963 amid the turmoil following the Diem assassination, or in late 1964 or early 1965 in the face of increasing political and military weakness in South Vietnam.” Robert McNamara, of all people, had vindicated in advance the premise of my fictional enterprise. I felt something I can only describe as queasy glee.

3.

My high opinion of The Fog of War bred high expectations for Believing is Seeing, and, as I’ve said, there is much in the book to admire. But Morris’ remark about “the photography police” gnawed at me. A second reading of Sontag’s writings on photography led me to the conclusion that Morris is not only a low-blow artist, he’s also less than completely truthful, which is a fatal flaw for someone on such a lofty quest for truth.

Roger Fenton was the first war photographer. Sent to the Crimea in early 1855 at the instigation of Prince Albert, Fenton was a lackey of the British government and the avatar of what we have come to call spin doctors. “Acknowledging the need to counteract the alarming printed accounts of the unanticipated risks and privations endured by the British soldiers dispatched there the previous year,” Sontag writes in Regarding the Pain of Others, “the government had invited a well-known professional photographer to give another, more positive impression of the increasingly unpopular war.” It was a botched war in dire need of some good publicity; it was the Great War sixty years before the Great War; it was Vietnam a century before Vietnam.

Sontag continues in this derisive vein: “Under instructions from the War Office not to photograph the dead, the maimed, or the ill, and precluded from photographing most other subjects by the cumbersome technology of picture-taking, Fenton went about rendering the war as a dignified all-male group outing.” Until, that is, he came upon the Valley of the Shadow of Death and all those cannonballs beside the road. Sontag calls Fenton’s photograph of the cannonballs on the road “a portrait of absence, of death without the dead,” adding that “it is the only photograph he took that would not have needed to be staged.” And yet it was staged! But – and here’s the crux of the matter – that staging made no difference to Sontag, just as it makes no difference to Morris. “With time,” she concludes, “many staged photographs turn back into historical evidence, albeit of an impure kind – like most historical evidence.” Believing Is Seeing, for whatever reason, neglects to mention this crucial conclusion.

Though Morris erred here, I think he is right to chide Sontag for declining to use photographs to illustrate her writings on photography. (The German writer W.G. Sebald solved this problem by including photographs in his books but shrewdly leaving out captions, forcing the reader to do the work of integrating the images and the prose.)

Delineating their differences should not overshadow the fact that Morris and Sontag see eye to eye on many questions. The slippery nature of photographs as factual evidence, for instance. In her seminal 1977 book On Photography, Sontag wrote, “Photographs, which cannot themselves explain anything, are inexhaustible invitations to deduction, speculation and fantasy.” Compare that with Morris’ claim that every photograph “should be a constant reminder – not of how photographs can be true or false – but of how we can make false inferences from a photograph.” He adds that every photograph’s tenuous claim to factuality has been greatly weakened by new technology, such as Photoshop. To his credit, he embraces this development as a spur to heightened vigilance and skepticism. Morris and Sontag also agree that posing is not necessarily deception, and that every photograph is, in a sense, staged because of the photographer’s decisions on how to frame the shot, when to release the shutter, how to crop the resulting print. Sontag takes this a step further, though, noting the “spasm of chagrin” that arises whenever people discover that a supposedly candid picture was staged. “What is odd,” she writes, “is not that so many of the iconic news photos of the past, including some of the best-remembered pictures from the Second World War, appear to have been staged. (What is odd) is that we are surprised to learn they were staged, and always disappointed.”

She’s thinking less about Roger Fenton here than about Robert Capa and Robert Doisneau: the former’s photograph of a Republican soldier in the act of falling from a fatal gunshot wound during the Spanish Civil War; and the latter’s 1950 photograph “Kiss by the Hotel de Ville,” which shows a young couple kissing, apparently spontaneously, on a Paris street. Sontag was aware that the authenticity of Capa’s photograph had come under question in the 1970s, but she was more interested in its jarring context than its dubious content. (The full-page picture was published in Life magazine in 1937, she notes, opposite a full-page ad for Vitalis hair tonic.) It wasn’t until five years after Sontag’s death that a Spanish researcher proved, beyond a doubt, that “Falling Soldier” was staged. The picture is formally titled “Death of a Loyalist Militiaman, Cerro Muriano, Cordoba Front, Spain, Sept. 5, 1936.” But the researcher determined that the picture was taken not at Cerro Muriano, just north of Cordoba, but near the town of Espejo, about 35 miles away. Capa was in Espejo in early September 1936 – but no fighting took place there until later in the month. So the researcher, José Manuel Suspesrregui, concluded that “the ‘Falling Soldier’ photo is staged, as are all the others in the series taken on that front.”

She’s thinking less about Roger Fenton here than about Robert Capa and Robert Doisneau: the former’s photograph of a Republican soldier in the act of falling from a fatal gunshot wound during the Spanish Civil War; and the latter’s 1950 photograph “Kiss by the Hotel de Ville,” which shows a young couple kissing, apparently spontaneously, on a Paris street. Sontag was aware that the authenticity of Capa’s photograph had come under question in the 1970s, but she was more interested in its jarring context than its dubious content. (The full-page picture was published in Life magazine in 1937, she notes, opposite a full-page ad for Vitalis hair tonic.) It wasn’t until five years after Sontag’s death that a Spanish researcher proved, beyond a doubt, that “Falling Soldier” was staged. The picture is formally titled “Death of a Loyalist Militiaman, Cerro Muriano, Cordoba Front, Spain, Sept. 5, 1936.” But the researcher determined that the picture was taken not at Cerro Muriano, just north of Cordoba, but near the town of Espejo, about 35 miles away. Capa was in Espejo in early September 1936 – but no fighting took place there until later in the month. So the researcher, José Manuel Suspesrregui, concluded that “the ‘Falling Soldier’ photo is staged, as are all the others in the series taken on that front.”

But “Falling Soldier” is such a treasured image in the anti-fascist pantheon that when an exhibition of Capa’s photographs opened in Barcelona in 2009, the culture minister in Spain’s socialist government felt the need to defend it through some linguistic contortions. “Art is always manipulation,” he said, “from the moment you point a camera in one direction and not another.” Agreed, but Morris cuts to the heart of the matter: “Posing is not necessarily deception. Deception is deception.” And no matter how you try to spin it, “Falling Soldier” is a deception, not because it was posed but because the death it claims to document was not real. Yes, people died in that fashion during that war, but no one died on that day in that place. As Sontag rightly stated it, “The point of ‘The Death of a Republican Soldier’ is that it is a real moment, captured fortuitously; it loses all value should the falling soldier turn out to have been performing for Capa’s camera.”

As for “The Kiss,” Doisneau finally admitted in 1992 that he had paid two young lovers (who happened to be aspiring actors) to repeat their kiss at various Paris locations four decades earlier. After the truth came out, the woman in the picture, Francoise Delbart, proclaimed, “The photo was posed. But the kiss was real.”

And that, our two heavyweights would agree, is all that matters.

Image credits:

Fenton, “Valley of the Shadow of Death” with road cleared of cannonballs via Wikimedia Commons

Fenton, “Valley of the Shadow of Death” with road full of cannonballs via Wikimedia Commons

Robert Doisneau, “Kiss by the Hotel de Ville” via Masters of Photography