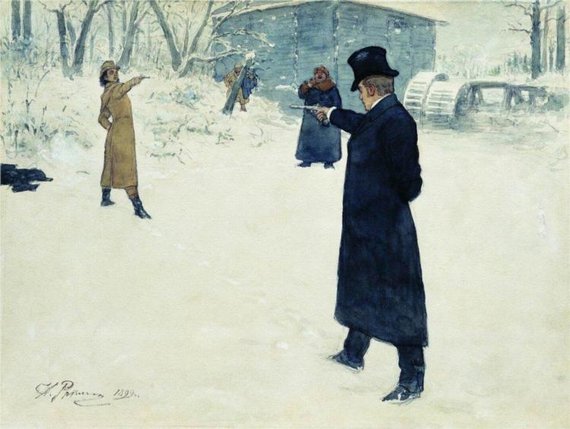

Ilya Repin, Duel Between Onegin and Lenski, from Alexander Pushkin‘s Eugene Onegin, 1899 (source)

1.

In her article “The Emergence of the Duel in Russia,” which appeared in a 1995 edition of Russian Review, Irina Reyfman wrote, “the first third of the nineteenth century stands out in Russian cultural memory as a period that saw the largest number of duels in the history of dueling Russia.” Its sudden popularity, she argued, grew from mounting tension between the nobility and the reactionary Tsar Nicholas I. Fed up with their shrinking autonomy, the nobles utilized the threat of the duel to preserve the inviolability of their rights.

As it happened, the first third of the nineteenth century was also the height of the Golden Age of Russian Poetry, and so unsurprisingly the literature of the time often crossed paths with the act of dueling. Yet while the duel, according to Reyfman, enjoyed its peak popularity during Russia’s Golden Age, it would not fully fall out of fashion—or literary relevance—until Russia’s Silver Age a hundred years later.

2.

Two events in particular punctuate the beginning of the era. Another marks its end.

In 1837, Alexander Pushkin and Georges d’Anthès dueled on the banks of St. Petersburg’s Chernaya River. Offended by allegations that his brother-in-law, d’Anthès, was having an affair with his wife, Pushkin challenged the French officer to mortal combat. It would be Pushkin’s twenty-ninth duel, and it would also end his life. Four years afterward, Mikhail Lermontov would die in the same way: killed by Nikolai Martynov over a crass joke. (That Pushkin and Lermontov died so close together underscores what Reyfman said about the duel’s sudden popularity.)

Nearly a century later, in 1909, two more Russian poets dueled on the Chernaya Rechka: Nikolay Gumilyov and Maximilian Voloshin. The offense seems cliché at first: Gumilyov had—like many of his peers—become enamored with the female poet Cherubina de Gabriak, and Voloshin stood in his way. It was soon discovered, however, that de Gabriak did not actually exist in corpus, and was instead a pseudonym manufactured by Voloshin and a then-unknown schoolteacher named Elisaveta Dmitrievna. The two had concocted the exotic alias in order to get two dozen poems published. Gumilyov, publisher of some of these poems, wound up penning amorous letters to de Gabriak, and he began receiving equally amorous responses. The offense could not go unpunished. This time, both duelists survived unscathed.

3.

Yet to understand how such sophisticated men came to duel, we’ll need a history primer.

Unlike Medieval Europe, Medieval Russia did not know jousting or any of the other tournaments which historically evolved into duels. Instead, the “honor duel” entered Russia through its military. Soldiers stationed abroad learned of the practice or, more often, foreign enlistees in the tsarist military would duel against one another. What many consider to be the first duel on Russian soil occurred in 1666 between a major and a Scotsman. For a century and a half afterward, it rarely occurred at all.

Popular anecdotes, however, began lending a faux honorability to the duel, and before long myth trumped veracity. Duelists became heroes. Military courts legitimized the act by prescribing duels to feuding officers, and these officers were usually of noble birth. When their military service ended, they took the duel home with them, and the act began to spread.

Still, civilian duels were nearly invisible. As readers of Eugene Onegin know, duels were generally held in secret. Due to a slew of legal restrictions meant to stifle the act’s proliferation, nobles most often met in the pre-dawn hours.

Still, civilian duels were nearly invisible. As readers of Eugene Onegin know, duels were generally held in secret. Due to a slew of legal restrictions meant to stifle the act’s proliferation, nobles most often met in the pre-dawn hours.

But something changed in the early 1800s, and the act emerged from the shadows to become relatively commonplace among the upper classes. Increasingly resentful of their imperial monarch (for a whole bunch of reasons), nobles stopped hiding their duels. The right to duel became a defiant expression of the nobility’s burgeoning sense of entitlement. Many Decembrists made names for themselves as bretteurs. Nobles challenged one another to redeem offenses, and they also challenged government officials when their privileges felt threatened. In fact, before challenging his brother-in-law, Pushkin wanted to duel Tsar Nicholas over the same controversy.

Of course, this being an age of uneven education, the prominent literary players often hailed from the ranks of this same upper class. Poets and writers, then, began committing duels to verse. They glorified the courageous acts of their peers and forebears. And since the primary consumers of literature at the time were also of the nobility, these self-serving fictional accounts stuck.

4.

But something was awry in these literary portrayals: they were often anachronistic. In an effort to make the fashionable perennial, or to add depth to the shallow, many writers painted the duel as a storied tradition rather than the sudden fad that it really was.

According to Reyfman, it began with Aleksander Bestuzhev-Marlinsky’s 1824 story “Castle Neihausen.” Set in 1334, the story features two dueling characters a full 300 years before the act’s Russian import. While Eugene Onegin grounded the duel in the correct time period, Pushkin’s The Captain’s Daughter made the duel seem as popular in the 1770s as it would be decades later. By the time Ivan Turgenev published “Three Portraits” in 1846, nobody thought it odd that its protagonist was an avid duelist in the 18th century. The myth had grown legs.

According to Reyfman, it began with Aleksander Bestuzhev-Marlinsky’s 1824 story “Castle Neihausen.” Set in 1334, the story features two dueling characters a full 300 years before the act’s Russian import. While Eugene Onegin grounded the duel in the correct time period, Pushkin’s The Captain’s Daughter made the duel seem as popular in the 1770s as it would be decades later. By the time Ivan Turgenev published “Three Portraits” in 1846, nobody thought it odd that its protagonist was an avid duelist in the 18th century. The myth had grown legs.

These fictions set precedent where history afforded none, and manufactured history became cultural memory. (If this idea seems far-fetched, see who among your peers believes Paul Revere rode alone.) As Reyfman puts it, people clung to “this anachronistic treatment of the duel” because “it reflected the nineteenth-century nobility’s presumption (or, perhaps wishful thinking) that their ancestors had adhered to the honor code.” Put another way, fictional narratives conveniently bolstered contemporary desire. Think about it: would you rather believe you were enforcing an ancient honor code or acknowledge the fact that your murderous desire is barbarous and shameful?

5.

By the turn of the 20th century, the duel had become so prominent in Russian literature that two separate stories entitled The Duel were published fourteen years apart. Published in 1891, Anton Chekhov’s novella is the better-known of the two, but Alexander Kuprin’s 1905 novel deserves credit for demolishing the duel’s romantic mythology. Underscoring the inseparability of the two portrayals, Melville House bundled them together in their “The Duel x5” set this year.

Set in a provincial outpost on the fringes of the Russian Empire, Kuprin’s The Duel focuses on a platoon leader named Romashov. Young, manic, and bored beyond words, he and his fellow military officers spend their time drinking and gambling with each other, stopping occasionally to visit local brothels. They are never heroic; much less do they abide by an honor code. Early on, Romashov breaks off relations with an officer’s wife in order to pursue the affections of another kept woman. He and the officers repeatedly harass any Jews they encounter. These men, therefore, are not the passionate and romantic characters of Pushkin, and nor are they the well-reasoned and sympathetic men of Chekhov. These men are depraved, their lives are miserable, and that such miscreants settle their scores with a duel proves how low the act of dueling had actually been.

Set in a provincial outpost on the fringes of the Russian Empire, Kuprin’s The Duel focuses on a platoon leader named Romashov. Young, manic, and bored beyond words, he and his fellow military officers spend their time drinking and gambling with each other, stopping occasionally to visit local brothels. They are never heroic; much less do they abide by an honor code. Early on, Romashov breaks off relations with an officer’s wife in order to pursue the affections of another kept woman. He and the officers repeatedly harass any Jews they encounter. These men, therefore, are not the passionate and romantic characters of Pushkin, and nor are they the well-reasoned and sympathetic men of Chekhov. These men are depraved, their lives are miserable, and that such miscreants settle their scores with a duel proves how low the act of dueling had actually been.

Without giving too much away, the most telling aspect of Kuprin’s work is the duel’s absence from the narrative. Opening the novel, one might expect to be immediately thrust into the conflict leading to mortal combat. This doesn’t happen. Instead, for 300+ pages, the writer only uses the word “duel” about a half dozen times, and when the title act is set to occur, it is glossed over entirely. We do not get a real-time portrayal of the fight. We do not even get an extensive description of it afterward. Instead, the reader, like the ordinary Russian in the late-19th to early-20th century, has only a peripheral awareness of the duel: the knowledge that it may have taken place, but that it was also exceedingly rare, quite secretive, and ultimately less visible than certain poets would have you believe.