The July/August 2011 issue of Poets & Writers contains an interesting nugget from William Giraldi, author of the recently published novel Busy Monsters, his first. He says, “There’s obscene pressure on writers to be the next hot young thing…But let’s be honest: Most hot young things have nothing of value to say.” Pretty tough words for a 36-year-old. Not to imply any judgment of his novel one way or the other — I have not read it and do not know him — but by my lights, he’s still something of a hot young thing himself. His comment carries a special irony within this particular issue of Poets & Writers. Not only the cover story but also two other lengthy articles are about some aspect of debut fiction. In the grants and awards section, there are no fewer than six announcements for awards, fellowships, or professorships that are only available either to writers making their debut or writers under 35 or 40. Despite Giraldi’s comforting words, this issue of the magazine put me over the edge. “Damn it,” I thought. “Why do the kids get so much of the good stuff?”

I’m picking on Poets & Writers here but, as Giraldi notes, it is simply going along with the crowd. From the National Book Association’s “5 Under 35” to The New Yorker’s “20 Under 40” to the Bard Fiction Prize (under 40) to the New York Public Library’s Young Lions award (under 35) and on and on, the publishing and awards-giving biz has decided, along with the apparatus that promotes authors and their work (magazines, newspapers, websites, etc.) that the kids are all right. But where does that leave us oldsters (by which I mean those of us on the far side of 40)?

Of course, there are non-age-restricted prizes such as the Guggenheim, the NEA, and others open to mid-career, middle-aged writers. These awards all serve an important purpose — and they are all ferociously competitive. Do you know how many Guggenheim fellows there were in fiction, creative nonfiction, and poetry last year? Twenty-six, out of literally thousands of applicants. And they weren’t all over 40. Yes, sometimes a Jaimy Gordon or Julia Glass will squeak through to the big time with an unexpected major prize (the National Book Award in both their cases). But once you pass 40, if you’re not part of a small, largely white, male, extremely-talented-but-still coterie (you know who you are, Eugenides, Franzen, and Chabon), that’s rare.

Of course, there are non-age-restricted prizes such as the Guggenheim, the NEA, and others open to mid-career, middle-aged writers. These awards all serve an important purpose — and they are all ferociously competitive. Do you know how many Guggenheim fellows there were in fiction, creative nonfiction, and poetry last year? Twenty-six, out of literally thousands of applicants. And they weren’t all over 40. Yes, sometimes a Jaimy Gordon or Julia Glass will squeak through to the big time with an unexpected major prize (the National Book Award in both their cases). But once you pass 40, if you’re not part of a small, largely white, male, extremely-talented-but-still coterie (you know who you are, Eugenides, Franzen, and Chabon), that’s rare.

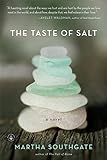

I realize this sounds bitter. And I have no business being bitter. I am a 50-year-old African-American woman whose fourth novel arriving in stores now. My work has always been published by major houses. Given the current climate in the book business, I am well aware that this is close to a miracle, especially for someone whose novels, though well-regarded, have sold modestly. I’ve enjoyed a couple of prestigious fellowships and won some prizes; when I look at it objectively, I know I’ve got it good – far better than many.

I realize this sounds bitter. And I have no business being bitter. I am a 50-year-old African-American woman whose fourth novel arriving in stores now. My work has always been published by major houses. Given the current climate in the book business, I am well aware that this is close to a miracle, especially for someone whose novels, though well-regarded, have sold modestly. I’ve enjoyed a couple of prestigious fellowships and won some prizes; when I look at it objectively, I know I’ve got it good – far better than many.

But this isn’t just about me (well it is partly, but not entirely). It’s about the extraordinary and damaging degree to which youth gets exalted in the status game of publishing and publicity. Not to take anything away from the many talented folks under 40, but where are the non-Pulitzer/National Book Award-level prizes for those of us who’ve been in there pitching for a while? Where’s The New Yorker’s “20 Over 40?”

By the time you get to your third, fourth, fifth major piece of fiction or non-fiction, ideally, you’ve settled into an expansion and deepening of your skills and talents as a writer. Even if you start late (say, at the ripe old age of 36), with any luck, your later novels will be better than your first. Yes, there are those who write only one book, or whose first book is their best. (Ralph Ellison, anyone?) And there are those who don’t, in fact, progress. But if you hang in there and read and push yourself, odds are that your later books will achieve a richness and nuance that your first one can’t. It is true that sometimes, past a certain point, it becomes a game of diminishing returns artistically (that’s another essay), but for many writers, mid-career is when they produce their best work. Off the top of my head: Beloved is Toni Morrison’s fifth novel. The Hours is Michael Cunningham’s third (fourth, if you count his disavowed first novel, Golden States). The Remains of the Day is Kazuo Ishiguro’s third novel. The Great Gatsby is F. Scott Fitzgerald’s third. Even the above-named contemporary big three — Eugenides, Franzen, and Chabon — hit their stride after writing one, two, even three novels. For my part, when I look back at my own fiction, I can see how my work has grown stronger and cleaner (for a small example, I used the word “weird” WAY too much in my first book.)

As Giraldi notes and as we all know, we live in a youth-obsessed culture. And really, is there any reason publishing should be different? I say yes, emphatically. Part of the reason we write is to consider as many facets of the human condition as possible. And the longer you live, the more of that darn thing you will find yourself confronted with.

So God bless the whippersnappers. I wish the best of them the best of luck. But the next time some wealthy patron of literature wants to endow a chair or offer a grant or a fellowship, or the next time a literary magazine wants to bestow a mantle, here’s hoping the requirements will be: “Applicants must be over 40 and have published at least one book.”

Image credit: Mickey van der Stap/Flickr