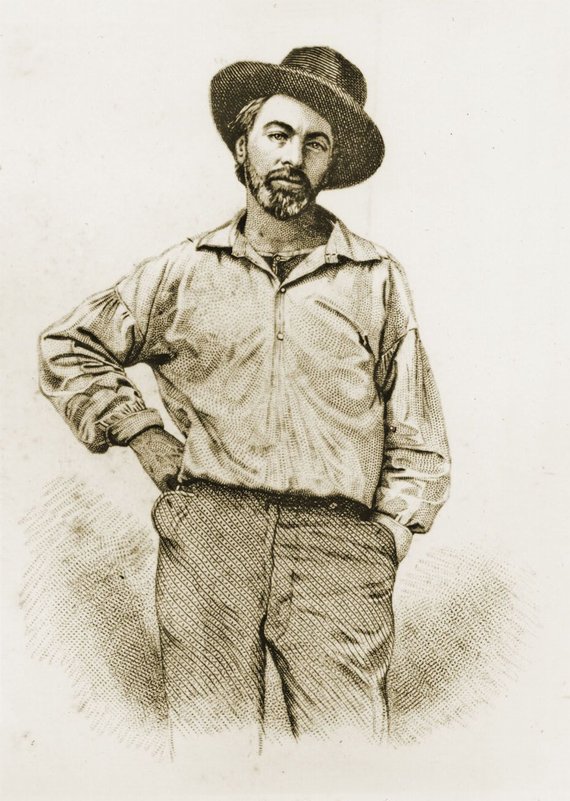

Walt Whitman. Bayley Collection, Ohio Wesleyan

1.

It sounds absurd for me to say that Walt Whitman saved my life, but it is true that at a particularly vulnerable period in my late twenties, my copy of the 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass was one of a very small handful of things that kept me from taking a flying leap off the Golden Gate Bridge. I was about to turn thirty and I was in graduate school in San Francisco, but that was less a legitimate occupation than an artfully crafted cover story for what was really going on in my life, which was that I was a drunk who’d stopped drinking and hadn’t yet found anything to replace the drug that had gotten me through the first twenty-odd years of my life.

It sounds absurd for me to say that Walt Whitman saved my life, but it is true that at a particularly vulnerable period in my late twenties, my copy of the 1855 edition of Leaves of Grass was one of a very small handful of things that kept me from taking a flying leap off the Golden Gate Bridge. I was about to turn thirty and I was in graduate school in San Francisco, but that was less a legitimate occupation than an artfully crafted cover story for what was really going on in my life, which was that I was a drunk who’d stopped drinking and hadn’t yet found anything to replace the drug that had gotten me through the first twenty-odd years of my life.

I went to class, I wrote papers, I taught my sections of comp, but really I was adrift. Anyone who has felt this way for any length of time knows that “adrift” isn’t a metaphor but a description of a physical fact. I would wake up in the middle of the night with the queasy sense that the bed I was in, the tatty little bedroom around me, the ground it all sat upon seemed strangely insubstantial. Temporary. Not to be trusted. Other nights I had dreams in which I simply ceased to exist. There I was, sitting in my parents’ living room or standing at the head of my classroom at school, screaming and screaming, but no one saw me, and worse, no one seemed to be particularly put out that I wasn’t there. The world went on its merry way as if I had never existed. Dreams like those made jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge sickeningly attractive. The fall would kill me, yes, but at least then I would be actually dead, at least then I would be missed.

It was during this time of profound personal crisis that I first read the famous opening lines of Whitman’s “Song of Myself”:

I celebrate myself,

And what I assume you shall assume

For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you.

I loafe and invite my soul,

I lean and loafe at my ease…observing a spear of summer grass.

I was doing a lot of leaning and loafing that year, but very little inviting of my soul. Like a lot of lost people, I assumed that my soul – “the other I am,” to use Whitman’s term for it – was the problem, and that inviting it too openly, too nakedly, would send me right over the side of the Golden Gate Bridge. This, I think, was the magic of Walt Whitman for me. Here was a poet who seemed on intimate terms with the darkest, most secret side of himself, but who, instead of running from that scarifying Other, embraced it, even celebrated it. “I exist as I am, that is enough,” Whitman writes. But how? How to find worth in that which I wished only to throw off a bridge? I probably read “Song of Myself” half a dozen times during that long, ugly summer in San Francisco. I read every Whitman biography I could find, and picked the brain of every scholar of American literature foolish enough to attend his own office hours, but in the end the answer was as simple as it was counterintuitive. You cannot escape your malevolent Other. It exists, as integral a part of you as your eyes and lungs, and there’s nothing to do except embrace it, open yourself to it and listen.

“I believe in you my soul,” Whitman writes in “Song of Myself”:

the other I am must not abase itself to you,

And you must not be abased to the other.

Loafe with me on the grass, loose the stop from your throat,

Not words, not music or rhyme I want, not custom or lecture, not even the best

Only the lull I like, the hum of your valved voice.

2.

Walt Whitman published the first edition of Leaves of Grass on July 4, 1855, seventy-nine years after the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The publication date cannot have been accidental. Whitman was a journalist and a fierce believer in a united United States, and six years before the outbreak of the Civil War, with Kansas bleeding and the country riven by sectional strife, Whitman saw Leaves of Grass as, among other things, a sort of poetical pamphlet that could somehow sing the nation into unity.

Things didn’t work out that way, but it wasn’t for lack of trying. Because he knew he would never find a legitimate publisher for such a strange book, Whitman published the first edition himself, setting much of the type on his own in a print shop at the corner of Cranberry and Fulton streets in Brooklyn. The finished book is a marvel of enigmatic charm. The twelve poems, each of which fill many pages and make use of no traditional schemes of rhyme or meter, were untitled, and the title page makes no mention of an author, offering instead only an engraving of a young bearded man wearing a slouch hat and an insouciant expression, staring at the reader as if daring him or her to open the book. It is only much later, 499 lines into the first poem, that one hears of “Walt Whitman, an American, one of the roughs, a kosmos,” who is, apparently, the all-seeing “I” of the poem, and maybe, too, its author.

If you have read Leaves of Grass for a high school or college course or from a copy you found at a bookstore or library, chances are you have not read the 1855 edition. Until the very last weeks of his life, Whitman continued to put out new editions of Leaves of Grass, each time adding new poems and revising the old ones, so that by the time he published the 1892 so-called Death-Bed Edition, the version most often sold in stores or excerpted in anthologies, he had expanded the original twelve poems to 383. Some of these later poems are works of genius, from the long, symbol-rich elegy, “When Lilacs Last In the Dooryard Bloom’d,” to tiny sparkling gems like “O Captain! My Captain!” and “A Noiseless, Patient Spider.” But many of Whitman’s later poems, especially those written after he suffered a paralytic stroke in 1873, are truly godawful: windy, oracular, abstract, and just plain boring. Worse, his revisions of his earlier poems, especially “Song of Myself,” suffer from the same deadening impulse to edit out the slangy wit and quirky Yankeeisms and make the whole thing sound like Poetry with a capital P.

So, if you care about American poetry, but have always found Whitman gassy and dull, you owe it to yourself – right now – to get your hands on the Penguin Classics edition of the 1855 Leaves of Grass. Read Malcolm Cowley’s brilliant, and extremely useful, introduction; skip Whitman’s own interminable prose introduction; and read the poems as they were originally meant to be read.

3.

The first edition of Leaves of Grass is a poetical Declaration of Independence in so many ways it can be hard to keep track of them all. In Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography, David Reynolds makes the case for a largely political reading of Whitman, arguing that the poet, profoundly troubled by the turmoil of his time, was trying to heal the country with a poem. Cowley, in his introduction to the 1961 Penguin Classics edition, posits Whitman as a home-grown mystic, unconsciously translating the central tenets of Eastern religious thought for a nineteenth century Western reader. Students of literary history have claimed him as a master formal innovator, crediting him with freeing the poetic line from the strictures of rhyme and meter. More recently, queer theorists, citing Whitman’s close relationships with younger men and his homoerotic “Calamus” poems, have promoted him as the Good Gay Poet.

The first edition of Leaves of Grass is a poetical Declaration of Independence in so many ways it can be hard to keep track of them all. In Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography, David Reynolds makes the case for a largely political reading of Whitman, arguing that the poet, profoundly troubled by the turmoil of his time, was trying to heal the country with a poem. Cowley, in his introduction to the 1961 Penguin Classics edition, posits Whitman as a home-grown mystic, unconsciously translating the central tenets of Eastern religious thought for a nineteenth century Western reader. Students of literary history have claimed him as a master formal innovator, crediting him with freeing the poetic line from the strictures of rhyme and meter. More recently, queer theorists, citing Whitman’s close relationships with younger men and his homoerotic “Calamus” poems, have promoted him as the Good Gay Poet.

What makes Whitman such an important figure, and makes “Song of Myself” the only true aspirant to the title of Great American Poem, is that these commentators are all basically right. Whitman was queer as a three-dollar bill, and though it’s unlikely he ever read the Bhagavad-Gita or any other foundational texts of Eastern religion, there is no question his poems espouse a deeply un-Western view on humanity and the divine. He was also an important formal innovator. Before Whitman, Western poetry adhered to rules of rhyme and meter built for a time when printing was an expensive, time-consuming process and poetry was largely an oral art form. Whitman, a newsman whose career coincided with technological advances in the printing press that paved the way for cheap, widely distributed pamphlets and newspapers, saw before anyone else how these advances could free verse from the restrictions of rhyme and meter. Finally, while some teachers may be guilty of playing up his more patriotic poems in order to play down his more uncomfortable private ones, it is clear that Whitman saw the 1855 edition as a poetical means toward a political end. The book’s central image, the leaf or blade of grass, is an overt symbol of democratic equality, “Sprouting alike in broad zones and narrow zones/Growing among black folks as among white,/Kanuck, Tuckahoe, Congressman, Cuff, I give them the same, I receive them the same.”

What makes Whitman such an important figure, and makes “Song of Myself” the only true aspirant to the title of Great American Poem, is that these commentators are all basically right. Whitman was queer as a three-dollar bill, and though it’s unlikely he ever read the Bhagavad-Gita or any other foundational texts of Eastern religion, there is no question his poems espouse a deeply un-Western view on humanity and the divine. He was also an important formal innovator. Before Whitman, Western poetry adhered to rules of rhyme and meter built for a time when printing was an expensive, time-consuming process and poetry was largely an oral art form. Whitman, a newsman whose career coincided with technological advances in the printing press that paved the way for cheap, widely distributed pamphlets and newspapers, saw before anyone else how these advances could free verse from the restrictions of rhyme and meter. Finally, while some teachers may be guilty of playing up his more patriotic poems in order to play down his more uncomfortable private ones, it is clear that Whitman saw the 1855 edition as a poetical means toward a political end. The book’s central image, the leaf or blade of grass, is an overt symbol of democratic equality, “Sprouting alike in broad zones and narrow zones/Growing among black folks as among white,/Kanuck, Tuckahoe, Congressman, Cuff, I give them the same, I receive them the same.”

But for the non-specialist reader – which is to say for readers like myself – it is the personal side of his poetry that resonates most deeply. Much is made in the academic world of the omniscient, omnivalent “I” at the center of Leaves of Grass, but a lay reader is just as likely to note the second most important character in the poems, which is nearly always “you.” Whitman is the most intimate of poets, and surely among the most genuinely concerned for the comfort and welfare of his readers. “How is it with you?” he asks in the opening stanzas of “A Song for Occupations,” the second poem in the 1855 edition. “I was chilled with the cold types and cylinder and wet paper between us.” One of the primary effects of the relaxed poetic line is the way it turns that most formal of literary interactions – a person reading a poem – into a conversation, you and old Walt, bellies to the bar, shooting the shit about the state of your immortal soul.

It was this intimacy, the sense Whitman creates in the original poems that not only is he talking to you but listening as well, that drew me in during that awful year in San Francisco. I was a young man who needed a good talking to, but also one yearning to be heard. I was living, like a lot of lost, lonely people, in a closed ecosystem of my own neuroses, which thrived on hours spent in bed mentally composing suicide notes that would, depending on my mood, devastate my loved ones or bring tears to their eyes at the lost promise of my genius. This was all so crazy I couldn’t possibly tell anyone, yet I desperately needed someone to tell. So, by some alchemical literary process I do not understand to this day, Walt Whitman became my confessor and courage-teacher. I sensed, correctly I think, that Whitman “got” it. He’d been there 150 years before I had, and if I could just teach myself how to listen to him, he might teach me how to stay alive.

And he did. The central tension in the poems in the 1855 edition is between “I” and “you.” The poet is constantly yearning to reach out to you; or reeling from contact with you; or entering into you, thinking your thoughts and feeling your feelings. But who is this you? Sometimes it’s the reader, while at other times it is some stranger the poet has picked out of the crowd, and at still other times it is “my soul” or the “other I am.” After many readings and re-readings, it occurred to me that what I had at first taken to be a conflation of “you’s,” or, worse, a simple confusion, was in fact the whole damn point. What Whitman is saying in Leaves of Grass is that we are all one and the same, not just in the political sense that the slave is equal in worth to the slave master, but that we are all intimately linked in one unbreakable chain of being. The fact that you exist is enough, because whether you have “outstript…the President” or are a “prostitute draggl[ing] her shawl,” by the mere fact of existing you take your rightful place in a miraculous, inter-connected system called the world.

This is why Walt Whitman, or you, or I can cock our hats as we please indoors or out, because no matter who we are, we are just as good and just as necessary as everyone else. But for me it also offered a route out of my endless, self-constructed maze of Self. If there is no wall between I and you, if we are all one and the same, what’s the point of hiding one from the other? Why not acknowledge that part of myself that wanted to die? Why not tell someone that while I never wanted to drink again, I was afraid I might lose my mind if I didn’t? Why not tell my parents I wasn’t the perfect son I wanted them to think I was? Why not sit in a church basement full of strangers, as I did once toward the end of that summer, crying like a baby because a woman had left me and I couldn’t blame her? Why not, if only for this one day, dare to be fully and completely alive?

4.

That awful year is now years behind me and it is hard for me to conjure up the mad cocktail of loneliness, despair and naivety that could make a grown man seek life-saving advice from a book of poems. But I also know that I am not alone. One day not long after I first read the 1855 edition I was at a meeting in a church basement near San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, when an older guy named Tom raised his hand to speak. I had always liked Tom. He was clean and well-kempt and we’d had a few very nice discussions about books, notwithstanding the fact that he was off-his-meds crazy and lived in a pup tent in a thicket of trees near Spreckels Lake in Golden Gate Park. In any case, on this day Tom stood up, and without preamble, began to speak:

Through me many long dumb voices,

Voices of interminable generations of slaves,

Voices of prostitutes and of deformed persons,

Voices of the diseased and despairing, and of thieves and dwarves,

I am certain that I was the only person in the room who recognized this as Whitman, from Canto 24 of “Song of Myself.” I am just as certain that I was the only person who really listened to him. Tom was a known crazy, and after the first few lines the regulars went back to sipping their lukewarm coffee and checking out the cute young junkie fighting the shakes in her chair by the door. Me, I sat transfixed. It wasn’t just that I recognized the words; it was the way Tom was saying them, with great gusto and energy, as if he were not merely reciting the famous lines of a dead poet, but speaking spontaneously, one finger plugged into the godhead, saying whatever came into his mind. It occurred to me sitting there that Tom was Walt Whitman, or as close to him as I was going to get in my lifetime. He was everything I feared, that terrifying “other I am,” the nice, bright, well-educated guy who had somehow gone horribly wrong and ended up sleeping in a public park and reciting poetry to strangers.

“Divine I am inside and out,” he raved,

and I make holy whatever I touch or am touched from;

The scent of these armpits is aroma finer than prayer,

This head is more than churches or bibles or creeds.

There were some chuckles when Tom got to the bit about the aroma of his armpits being finer than prayer, but I didn’t laugh. I didn’t feel pity, either. Instead, I leaned back in my chair, for once taking my mind off the lukewarm coffee in my hands and the cute junkie girl by the door, and just listened.