Though I could easily rattle off the titles of two dozen novels I love, cherish, and reread, I would struggle to name half a dozen short stories that affected me similarly. I simply don’t love the short form. That was until I read my first Rebecca Makkai short story “The Briefcase”. I fell in love with the form that day— at least Makkai’s version of it— and I wasn’t surprised when Alice Sebold chose it for the 2009 The Best American Short Stories anthology.

Others are smitten with Makkai’s work, too. Salman Rushdie, Richard Russo, Geraldine Brooks, and Dave Eggers have all chosen Rebecca’s short stories for anthologies. This, again, is no surprise. Her first sentences and paragraphs coax readers into the narrative and before they realize, Makkai is ferrying them on an adventure that enthralls, resonates and, often times, disconcerts.

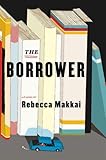

She has done it again with her debut novel, The Borrower. The first pages drew me into the story as 10-year-old Ian Drake lures children’s librarian Lucy Hull into his life. Before Lucy fully understands the situation and its implications of her involvement with young Ian, she is off on a surreptitious, cross-country escapade with her most enthusiastic patron.

She has done it again with her debut novel, The Borrower. The first pages drew me into the story as 10-year-old Ian Drake lures children’s librarian Lucy Hull into his life. Before Lucy fully understands the situation and its implications of her involvement with young Ian, she is off on a surreptitious, cross-country escapade with her most enthusiastic patron.

I conducted this interview by email as the last time Rebecca and I met, we lost track of time and I missed two trains and had to literally run to catch a third.

The Millions: Like your main character, your occupation brings children to great books. How did your experience as an elementary school teacher influence your characterization of the librarian Lucy Hull?

Rebecca Makkai: I’ve read out loud to children for half an hour every school day for the past eleven years, and that daily engagement with children’s books has kept them very much a part of my literary landscape. And part of my job is to be a book-pusher. At times I feel a bit like some skeezy drug dealer, hanging out at the edge of the playground, going, “If I can get them to try it just this once, I’ll have them hooked!”

Although I’m a very different person than Lucy, and her world is pure fiction, I did use that one element of my own life – the sublime satisfaction of connecting children with the books that will become their favorites. What makes that same feeling urgent and even desperate in Lucy’s case is the fact that this is one of the only ways she can help her patron Ian, who is being fed a whole different set of fictions – very damaging ones – by his parents and church.

TM: Though Lucy is first reluctant to acknowledge the sexuality of 10-year-old Ian, she acts when Ian’s religious parents take him to a church that specializes in gay reprogramming. Was this church – Glad Heart Ministries – based on a real group?

RM: Disturbingly, it was inspired by many, many different groups, though none directly. One of the largest and most egregious programs is Exodus International, which has hundreds of chapters, a youth ministry, and even (no kidding) an iPhone app – although, to be fair, they’re actually not the most hateful group out there, by a long shot. We never meet “Pastor Bob” in the book, but the few things we do learn about him are remarkably predictable of the leaders of these groups – including his being caught in a gay bar and trying to play it off.

TM: Ultimately, it is Lucy’s belief in the power and complexity of fiction that allows her to let go of Ian. Is her faith in the fictional narrative similar to your own?

RM: If you consider not just books but also movies, TV shows, fairytales, urban legends, the narratives of song lyrics and video games, etc., it’s clear that despite doomsday laments about the demise of literature, we are still a species that lives in fictional worlds almost as much as in the real one. We need stories on some fundamental level that go far beyond any one medium or industry, and I think we need them for the same reasons we need to dream. You know how if you keep someone from dreaming in a sleep lab, they go crazy? I imagine the same might be true for absorbing fictions. And just as dreams allow us to work things out that we never could have understood consciously, I think narratives keep us sane by letting us process the world without the filter of our own lived experience. Lucy recognizes that for Ian, a story would be far more effective than a nonfiction book about growing up gay, which would just embarrass and distance him. What she doesn’t realize until later is how much her own senses of self and family have been predicated on some necessary and merciful fictions.

TM: What books directly influenced or inspired this novel?

RM: I kept both Lolita and Huckleberry Finn close on hand as I wrote, and these are books that Lucy uses as touchstones throughout. There are many riffs on classic children’s books (or certain types of book) scattered through the text, but in structure I tried to parallel those two and also The Wonderful Wizard of Oz as much as I could. And there’s some Catcher in the Rye thrown in for good measure… All the iconic runaway books are part of Lucy’s frame of reference, and the fact that (not coincidentally) they all share some similarities of structure made it easier to follow all of them simultaneously.

RM: I kept both Lolita and Huckleberry Finn close on hand as I wrote, and these are books that Lucy uses as touchstones throughout. There are many riffs on classic children’s books (or certain types of book) scattered through the text, but in structure I tried to parallel those two and also The Wonderful Wizard of Oz as much as I could. And there’s some Catcher in the Rye thrown in for good measure… All the iconic runaway books are part of Lucy’s frame of reference, and the fact that (not coincidentally) they all share some similarities of structure made it easier to follow all of them simultaneously.

TM: As a narrator, Lucy is slippery and unreliable. She claims to work at the public library in Hannibal, Missouri, but we later learn she has only adopted this town’s name for the sake of her story. Why did Lucy choose Hannibal to set off her road trip tale?

RM: Because it’s the starting point of Huckleberry Finn. In my mind (and, as implied in the story, in Lucy’s), Twain enshrined it as the ultimate launching pad for the American road story. It’s the middle of the country, the middle of nowhere, and yet it’s on the banks of this enormous river that can sweep you right out of town. An interested reader could find a lot of parallels there: a child and adult running away together, with a lot of bungling and a lot of confusion as to who’s rescuing whom. There’s also a passage when they cross the bridge to Cairo, Illinois that’s a very direct reference to Huck and Jim’s point of no return.

But yes, she is pretty slippery, isn’t she? I have a weakness for unreliable narrators. Because who’s ever met a reliable one in real life?

TM: While Ian is literally running away, Lucy is doing so metaphorically. Both are fighting against others’ perceptions of them. Lucy doesn’t accept the stereotype of the quiet, wallflower librarian, but she also doesn’t fully embrace her family’s rebellious nature. In this respect, you and Lucy are similar. Writers, like librarians, are perceived as being poorly dressed introverts and your earlier work was heavily influenced by your father’s experience in the failed 1956 Hungarian revolution. Is this novel as much about Lucy’s self-actualization as your own?

RM: Well, I am pretty poorly dressed right now, but that’s probably not what you’re really asking. Probably the only other element of the story that’s autobiographical, aside from the aforementioned book-pushing habit, is my experience as a first-generation American. My family isn’t Russian, and my father is a retired linguistics professor who (unlike Jurek Hulkinov) has no Mafia ties that I’m aware of, but the worldview that I grew up with, of seeing America as a miraculous but flawed refuge from quite recent danger, is one that infuses a lot of my fiction. And like Lucy’s family, the Hungarian side of my family has a fairly disturbing history – more disturbing than Lucy’s, actually, by quite a bit, although it’s not something I’m ready to write about yet.

The night before my wedding, my father asked me (for reasons that are still unclear) whether I considered myself an American. In some ways, I think this book is my answer.

TM: Both this novel and most of your short stories are political. What are the difficulties in writing politically charged fiction?

RM: I don’t find it difficult so much as unavoidable. It’s funny, even when I think I’m writing a very apolitical piece (because it’s not directly about politics or revolution), it will end up being about race or class. You’d think I’d be a loudly political person in real life, but really I limit myself to voting and occasionally talking back to NPR when I’m alone in the car. And maybe that’s just what my stories will always be about, whether I want it or not – in the way that a Roth story is always about sex and a John Irving story is always about dismemberment and bears.

I think that whether I’m writing about a revolution or a bomb shelter or a public library, what I’m drawn to is the power structure – who’s in charge, who’s being oppressed, who’s working their way up that ladder. There’s a lot of drama inherent in that, and it’s not so much that I have a political ax to grind as that this is where I tend to find the story.

I do think that if someone sets out to write fiction just to prove a certain political point, though, it becomes unbearable. It’s why I can’t stand Tolstoy. I think politics can be the subject, but not the point.

TM: You and your short works have appeared in The Best American Short Stories four times in a row. Did your writing process change significantly in order to write a novel?

RM: The Borrower actually had a very long gestation: I started it in 2000, long before I’d published any short fiction. It was several years before I began working on it seriously, and I abandoned it and came back to it many times in the nine years till its completion, but it was always there, lurking in the background.

I do have to switch gears, though, between short and long stories. The pacing is obviously very different: a short story will either compress a very long time into a few pages, or (more commonly) take a small moment and delve into every detail. As a novelist, unless you’re Virginia Woolf, you have to find the midpoint between those two extremes if you’re going to maintain the reader’s interest over the long haul. In The Borrower, I have three different (unmarked) sections with different paces: In the first part of the book, Lucy needs to see Ian’s deterioration over several months. When they leave town together, she becomes very aware of time, since every minute they’re gone makes her more culpable. Time is marked out very carefully in terms of hours, meals, days, nights. And then the last section backs off and gives a more telescopic view of the months and even years after the main incident. It’s not an uncommon structure in novels, of course – broad view, narrow focus, broad view – but I don’t think I ever was so consciously aware of it as a reader until I wrote this book.

The other adjustment I need to make between my shorter and longer work is in the depth and pace of characterization. Since you have fewer words in which to establish a character in a short story, you need (and can get away with) some broader strokes. In a novel, those broader strokes, piled over many pages, can come off as caricature. That said, most of the peripheral characters in The Borrower are intentionally larger-than-life, and I made the decision, for better or worse, to paint some of them with a very large brush – partly for comic effect, and partly because the world of this novel is a somewhat surreal one. In my novel in progress, that isn’t the case at all. I have to remind myself to slow down, and that we don’t need to know everything about a character the moment he opens his mouth.

TM: As a mother to a small child and infant and as a teacher who works full-time outside the home, how do you find time to balance your responsibilities and creative self? What advice would you give to writers who are struggling with this balance?

RM: Before you make me sound like a superhero, I should point out that there’s still some laundry on my closet floor from spring break. Which was almost three months ago. So I suppose the answer is that I let a lot of little things slide, in favor of the bigger things.

I also find that I do a lot of my writing when I’m not actually writing. In a very busy week, I might not get any real uninterrupted time at my computer (or that time might come when I’m too exhausted to use the English language responsibly), but then on Saturday I’ll hit the ground running with everything I’ve thought of all week long, in the shower, in the car, at the grocery store. I suppose it’s a slightly depressing modern take on Wordsworth‘s going off on those long walks in the lake country and coming home with odes fully composed. My version involves composing in the pediatrician’s waiting room, then hurrying off to Starbucks to type like a maniac.

The key for me is to find the middle ground between feeling sorry for myself and expecting too much of myself. Come to think of it, maybe that’s the key to everything.

TM: What other things are you working on?

RM: I’m trying to get my stories to gel into some sort of collection, but I feel like a camp counselor with a cabin full of unruly girls refusing to coexist. And I’m working on my second novel, which is tentatively called The Happensack. It’s the story of a haunted house and a haunted family, told in reverse. I’m rather smitten with it right now, which is probably why I’m neglecting the laundry.