Is it my imagination, or do an inordinate number of writers die in motor vehicle accidents? Maybe I tend to notice these grisly deaths because I’m a writer, an avid reader of obituaries, and also a car lover with a deep fear of dying in a crash. But I’m convinced by years of accumulated empirical evidence that writers outnumber the percentage of, say, nurses or teachers or accountants who die in car and motorcycle accidents. (Similarly, an inordinate number of musicians seem to die in plane crashes, including the Big Bopper, John Denver, Buddy Holly, Otis Redding, Ritchie Valens and Ronnie Van Zant, to name a few.)

Why do so many writers die in motor vehicle mishaps? Are they reckless drivers? Prone to bad luck? Likely to indulge in risky behavior? I don’t pretend to know the answer(s), but I have noticed, sadly, that writers who die in crashes are frequently on the cusp of greatness or in the midst of some promising project; sometimes they’re at the peak of their careers. I offer this list in chronological order, aware it isn’t exhaustive. Feel free to add to it in the comments. Think of this as a living tribute to writers who left us too soon:

T.E. Lawrence (1888-1935) – Lawrence of Arabia, David Lean’s Oscar-winning 1962 movie, opens with the death of its subject. T.E. Lawrence (played by Peter O’Toole), the archaeologist/warrior who helped unite rival Arab tribes and defeat the Ottoman Empire during the First World War, was whizzing along a road in rural Dorset, England, astride his Brough Superior SS100 motorcycle on the afternoon of May 13, 1935. A dip in the road obscured Lawrence’s view of two boys on bicycles, and when he swerved to avoid them he lost control and pitched over the handlebars. Six days later he died from his injuries. He was 46.

Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Lawrence’s account of his experiences during the Great War, made him an international celebrity, though he called the book “a narrative of daily life, mean happenings, little people.” An inveterate letter writer, Lawrence also published his correspondence with Winston Churchill, George Bernard Shaw, Noel Coward, E.M. Forster and many others. He dreamed that victory on the desert battlefield would result in an autonomous Arab state, but negotiators at the Paris peace conference had very different ideas, prompting Lawrence to write bitterly, “Youth could win but had not learned to keep: and was pitiably weak against age. We stammered that we had worked for a new heaven on earth, and they thanked us kindly and made their peace.”

Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Lawrence’s account of his experiences during the Great War, made him an international celebrity, though he called the book “a narrative of daily life, mean happenings, little people.” An inveterate letter writer, Lawrence also published his correspondence with Winston Churchill, George Bernard Shaw, Noel Coward, E.M. Forster and many others. He dreamed that victory on the desert battlefield would result in an autonomous Arab state, but negotiators at the Paris peace conference had very different ideas, prompting Lawrence to write bitterly, “Youth could win but had not learned to keep: and was pitiably weak against age. We stammered that we had worked for a new heaven on earth, and they thanked us kindly and made their peace.”

Seven Pillars of Wisdom still speaks to us today, as the U.S. fights two wars in the region during this convulsive Arab Spring. Lawrence could have been writing about Americans in Iraq when he wrote these words about his fellow British soldiers: “And we were casting them by thousands into the fire to the worst of deaths, not to win the war but that the corn and rice and oil of Mesopotamia might be ours.”

Nathanael West (1903-1940) – Nathanael West, born Nathan Weinstein, wrote just four short novels in his short life, but two of them – Miss Lonelyhearts and The Day of the Locust – are undisputed classics. After graduating from college he managed two New York hotels, where he allowed fellow aspiring writers to stay at reduced rates or free of charge, including Dashiell Hammett, Erskine Caldwell and James T. Farrell. When his first three novels – The Dream Life of Balso Snell (1931), Miss Lonelyhearts (1933) and A Cool Million (1934) – earned a total of $780, a demoralized West went to Hollywood to try his hand at screenwriting.

Nathanael West (1903-1940) – Nathanael West, born Nathan Weinstein, wrote just four short novels in his short life, but two of them – Miss Lonelyhearts and The Day of the Locust – are undisputed classics. After graduating from college he managed two New York hotels, where he allowed fellow aspiring writers to stay at reduced rates or free of charge, including Dashiell Hammett, Erskine Caldwell and James T. Farrell. When his first three novels – The Dream Life of Balso Snell (1931), Miss Lonelyhearts (1933) and A Cool Million (1934) – earned a total of $780, a demoralized West went to Hollywood to try his hand at screenwriting.

There he enjoyed his first success. He wrote scripts for westerns, B-movies and a few hits, then used his experiences in the trenches of the movie business to brilliant effect in his masterpiece, The Day of the Locust (1939), which satirizes the tissue of fakery wrapped around everything in Los Angeles, from its buildings to its people to the fantasies that pour out of its dream factories. The novel also paints a garish portrait of the alienated and violent dreamers who come to California for the sunshine and the citrus and the empty promise of a fresh start. West’s original title for the novel was, tellingly, The Cheated. It was eclipsed by John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath, which was a published a few weeks before it and went on to win the Pulitzer Prize, then was made into a hit movie. West wrote ruefully to his friend F. Scott Fitzgerald, “Sales: practically none.”

In April of 1940 West married Eileen McKenney. Eight months later, on Dec. 22, a day after Fitzgerald had died of a heart attack, West and McKenney were returning to their home in Los Angeles from a bird-hunting expedition in Mexico. Outside the farming town of El Centro, West, a notoriously bad driver, gunned his sparkling new Ford station wagon through a stop sign at high speed, smashing into a Pontiac driven by a poor migrant worker. West and McKenney were flung from the car and died of “skull fracture,” according to the coroner’s report.

Marion Meade, author of Lonelyhearts: The Screwball World of Nathanael West and Eileen McKenney, closes her book with what I think is a fitting eulogy: “Dead before middle age, Nat left behind no children, no literary reputation of importance, no fine obituary in the New York Times ensuring immortality, no celebrity eulogies, just four short novels, two of them unforgettable. When a writer lives only 37 years and ends up with very little reward, it might seem a waste, until you look at what he did. For Nathanael West, what he did seems enough.”

Marion Meade, author of Lonelyhearts: The Screwball World of Nathanael West and Eileen McKenney, closes her book with what I think is a fitting eulogy: “Dead before middle age, Nat left behind no children, no literary reputation of importance, no fine obituary in the New York Times ensuring immortality, no celebrity eulogies, just four short novels, two of them unforgettable. When a writer lives only 37 years and ends up with very little reward, it might seem a waste, until you look at what he did. For Nathanael West, what he did seems enough.”

Margaret Mitchell (1900-1949) – Gone With the Wind, Margaret Mitchell’s only novel, was published in the summer of 1936. By the end of the year it had sold a million copies and David O. Selznick had bought the movie rights for the unthinkable sum of $50,000. Mitchell spent the rest of her life feeding and watering her cash cow, work that was not always a source of pleasure. Her New York Times obituary said the novel “might almost be labeled a Frankenstein that overwhelmed her,” adding, “She said one day, in a fit of exasperation as she left for a mountain hideaway from the throngs which besieged her by telephone, telegraph and in person, that she had determined never to write another word as long as she lived.”

Margaret Mitchell (1900-1949) – Gone With the Wind, Margaret Mitchell’s only novel, was published in the summer of 1936. By the end of the year it had sold a million copies and David O. Selznick had bought the movie rights for the unthinkable sum of $50,000. Mitchell spent the rest of her life feeding and watering her cash cow, work that was not always a source of pleasure. Her New York Times obituary said the novel “might almost be labeled a Frankenstein that overwhelmed her,” adding, “She said one day, in a fit of exasperation as she left for a mountain hideaway from the throngs which besieged her by telephone, telegraph and in person, that she had determined never to write another word as long as she lived.”

She gave up fiction but continued to write letters, and her correspondence is filled with accounts of illnesses and accidents, boils and broken bones, collisions with furniture and cars. In fact, she claimed she started writing her novel because “I couldn’t walk for a couple of years.”

On the evening of Aug. 11, 1949, Mitchell and her husband John Marsh were about to cross Peachtree Street in downtown Atlanta on their way to see a movie. According to witnesses, Mitchell stepped into the street without looking – something she did frequently – and she was struck by a car driven by a drunk, off-duty taxi driver named Hugh Gravitt. Her skull and pelvis were fractured, and she died five days later without regaining consciousness.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, a writer whose familiarity with failure surely colored his opinion of Mitchell’s staggering success, said of Gone With the Wind, “I felt no contempt for it but only a certain pity for those who considered it the supreme achievement of the human mind.”

Albert Camus (1913-1960) – He had planned to take the train from Provence back to Paris. But at the last minute, the Nobel laureate Albert Camus accepted a ride from his publisher and friend, Michel Gallimard. On Jan. 4, 1960 near the town of Villeblevin, Gallimard lost control of his Facel Vega sports car on a wet stretch of road and slammed into a tree. Camus, 46, died instantly and Gallimard died a few days later. Gallimard’s wife and daughter were thrown clear of the mangled car. Both survived.

In the wreckage was a briefcase containing 144 handwritten pages – the first draft of early chapters of Camus’s most autobiographical novel, The First Man. It closely paralleled Camus’s youth in Algiers, where he grew up poor after his father was killed at the first battle of the Marne, when Albert was one year old. The novel was not published until 1994 because Camus’s daughter Catherine feared it would provide ammunition for the leftist French intellectuals who had turned against her father for daring to speak out against Soviet totalitarianism and for failing to support the Arab drive for independence in the country of his birth. Camus dedicated the unfinished novel to his illiterate mother – “To you who will never be able to read this book.” He once said that of all the many ways to die, dying in a car crash is the most absurd.

In the wreckage was a briefcase containing 144 handwritten pages – the first draft of early chapters of Camus’s most autobiographical novel, The First Man. It closely paralleled Camus’s youth in Algiers, where he grew up poor after his father was killed at the first battle of the Marne, when Albert was one year old. The novel was not published until 1994 because Camus’s daughter Catherine feared it would provide ammunition for the leftist French intellectuals who had turned against her father for daring to speak out against Soviet totalitarianism and for failing to support the Arab drive for independence in the country of his birth. Camus dedicated the unfinished novel to his illiterate mother – “To you who will never be able to read this book.” He once said that of all the many ways to die, dying in a car crash is the most absurd.

Randall Jarrell (1914-1965) – In his essay on Wallace Stevens, written when he was 37, the poet and critic Randall Jarrell wrote prophetically, “A good poet is someone who manages, in a lifetime of standing out in thunderstorms, to be struck by lightning five or six times… A man who is a good poet at forty may turn out to be a good poet at sixty; but he is more likely to have stopped writing poems.”

In the 1960s, as his 50th birthday approached, Jarrell’s poetic inspiration was in decline. While he didn’t stop writing poetry, he concentrated on criticism, translations and children’s books. He also sank into a depression that led him to slash his left wrist and arm in early 1965. The suicide attempt failed, and a month later his wife Mary committed him to a psychiatric hospital in Chapel Hill, N.C. He was there when his final book of poems, The Lost World, appeared to some savage reviews. In The Saturday Review, Paul Fussell wrote, “It is sad to report that Randall Jarrell’s new book… is disappointing. There is nothing to compare with the poems he was writing 20 years ago… (His style) has hardened into a monotonous mannerism, attended now too often with the mere chic of sentimental nostalgia and suburban pathos.”

Though stung, Jarrell returned to UNC-Greensboro in the fall, where he was a dedicated and revered teacher. In October he was back in Chapel Hill undergoing treatments for the wounds on his left arm. On the evening of Oct. 14, 1965, Jarrell was walking alongside the busy U.S. 15-501 bypass, toward oncoming traffic, about a mile and a half south of town. As a car approached, Jarrell stepped into its path. His head struck the windshield, punching a hole in the glass. He was knocked unconscious and died moments later from “cerebral concussion.” The driver, Graham Wallace Kimrey, told police at the scene, “As I approached he appeared to lunge out into the path of the car.” Kimrey was not charged.

Was it a suicide? A tragic accident? We’ll never know for sure. One thing we do know is that this brilliant critic, uneven poet and inspiring teacher died too young, at 51, the same age as his heroes Proust and Rilke.

Richard Farina (1937-1966) – There was a time when every young person with claims to being hip and literary absolutely had to possess a battered copy of Richard Farina’s only novel, that terrific blowtorch of a book called Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up To Me. Like a handful of other novels – Tropic of Cancer, On the Road, The Catcher in the Rye, Gravity’s Rainbow and Infinite Jest come immediately to mind – Farina’s creation was as much a generational badge as it was a book. Farina’s novel, which recounts the picaresque wanderings of Gnossos Pappadopoulis, was published in 1966, after Farina and his wife Mimi, Joan Baez’s sister, had become a successful folk-singing act. The best man at their wedding was Thomas Pynchon, who’d met Richard while they were students at Cornell.

Richard Farina (1937-1966) – There was a time when every young person with claims to being hip and literary absolutely had to possess a battered copy of Richard Farina’s only novel, that terrific blowtorch of a book called Been Down So Long It Looks Like Up To Me. Like a handful of other novels – Tropic of Cancer, On the Road, The Catcher in the Rye, Gravity’s Rainbow and Infinite Jest come immediately to mind – Farina’s creation was as much a generational badge as it was a book. Farina’s novel, which recounts the picaresque wanderings of Gnossos Pappadopoulis, was published in 1966, after Farina and his wife Mimi, Joan Baez’s sister, had become a successful folk-singing act. The best man at their wedding was Thomas Pynchon, who’d met Richard while they were students at Cornell.

On April 30, 1966, two days after the novel was published, there was a party in Carmel Valley, California, to celebrate Mimi’s 21st birthday. Richard decided to go for a spin on the back of another guest’s Harley-Davidson motorcycle. The driver entered an S-curve at excessive speed, lost control and tore through a barbed-wire fence. Farina died instantly, at the age of 29. Pynchon, who later dedicated Gravity’s Rainbow to Farina, said his friend’s novel comes on “like the Hallelujah Chorus done by 200 kazoo players with perfect pitch.”

Wallace Stegner (1909-1993) – For a writer who lived such a long and fruitful life – he was a teacher, environmentalist, decorated novelist and author of short stories, histories and biographies – Wallace Stegner does not enjoy the readership he deserves. “Generally students don’t read him here,” said Tobias Wolff, who was teaching at Stanford in 2009, the centennial of Stegner’s birth. “I wish they would.”

It was at Stanford that Stegner started the creative writing program and nurtured a whole galaxy of supernova talents, including Edward Abbey, Ernest Gaines, George V. Higgins, Ken Kesey, Gordon Lish, Larry McMurtry and Robert Stone. He won a Pulitzer Prize for fiction and a National Book Award but was ghettoized as “the dean of Western writers.” In a cruel irony, this writer who deplored “the stinks of human and automotive waste” was on his way to deliver a lecture in Santa Fe, N.M., on March 28, 1993, when he pulled his rental car into the path of a car bearing down on his left. The left side of Stegner’s car was crushed, and he suffered broken ribs and a broken collarbone. A heart attack and pneumonia followed, and he died in the hospital at the age of 84.

For all his love of the West, Stegner knew it was no Eden. He once told an interviewer: “The West is politically reactionary and exploitative: admit it. The West as a whole is guilty of inexplicable crimes against the land: admit that too. The West is rootless, culturally half-baked. So be it.”

Steve Allen (1921-2000) – Though best known as a television personality, musician, composer, actor and comedian, Steve Allen also wrote more than 50 books on a wide range of topics, including religion, media, the American educational system and showbiz personalities, plus poetry, plays and short stories. Lovers of Beat literature will always remember Allen for noodling on the piano while Jack Kerouac recited passages from On the Road on “The Steve Allen Show” in 1959.

On Oct. 30, 2000, Allen was driving to his son’s home in Encino, California, when his Lexus collided with an SUV that was being backed out of a driveway. Neither driver appeared to be injured in the fender bender, and they continued on their ways. After dinner at his son’s home, Allen said he was feeling tired and lay down for a nap. He never woke up. The original cause of death was believed to be a heart attack, but a coroner’s report revealed that Allen had suffered four broken ribs during the earlier collision, and a hole in the wall of his heart allowed blood to leak into the sac surrounding the heart, a condition known as hemopericardium.

On the day of his death Allen was working on his 54th book, Vulgarians at the Gate, which decried what he saw as an unacceptable rise of violence and vulgarity in the media.

W.G. Sebald (1944-2001) – It has been said that all of the German writer W.G. Sebald’s books had a posthumous quality to them. That’s certainly true of On the Natural History of Destruction, his magisterial little exploration of the suffering civilians endured during the Allied fire-bombing of German cities at the end of the Second World War. I should say his exploration of the unexplored suffering of German civilians, because the book is partly a rebuke, a challenge to his shamed countrymen’s willed forgetfulness of their own suffering.

W.G. Sebald (1944-2001) – It has been said that all of the German writer W.G. Sebald’s books had a posthumous quality to them. That’s certainly true of On the Natural History of Destruction, his magisterial little exploration of the suffering civilians endured during the Allied fire-bombing of German cities at the end of the Second World War. I should say his exploration of the unexplored suffering of German civilians, because the book is partly a rebuke, a challenge to his shamed countrymen’s willed forgetfulness of their own suffering.

I lived for a time in Cologne, target of some of the most merciless bombing. I’ve seen photographs of the city’s Gothic cathedral standing in a sea of smoking rubble. I’ve heard old-timers talk about the war – men grousing about the idiocy of their military officers, women boasting about how they cadged deals on the black market. But I never heard anyone say a word about the horror of watching the sky rain fire. Until Sebald dared to speak.

He produced a relatively short shelf of books – novels, poetry, non-fiction – but he was being mentioned as a Nobel Prize candidate until Dec. 14, 2001, when he was driving near his home in Norwich, England, with his daughter Anna. Sebald apparently suffered a heart attack, and his car veered into oncoming traffic and collided with a truck. Sebald died instantly, at the age of 57. His daughter survived the crash.

David Halberstam (1934-2007) – David Halberstam died working. On April 23, 2007 he was riding through Menlo Park, California, in the passenger seat of a Toyota Camry driven by a UC-Berkeley journalism student. They were on their way to meet Y.A. Tittle, the former New York Giants quarterback, who Halberstam was keen to interview for a book he was writing about the epic 1958 N.F.L. title game between the Giants and the Baltimore Colts. As the Camry came off the Bayfront Expressway, it ran a red light. An oncoming Infiniti slammed into the passenger’s side and sent the Camry skidding into a third vehicle. The Camry’s engine caught fire and Halberstam, 73, was pronounced dead at the scene from blunt force trauma. All three drivers survived with minor injuries.

Halberstam made his mark by winning the Pulitzer Prize in 1964 for his reporting in the New York Times that questioned the veracity of the men leading America’s war effort in Vietnam. Eight years later he published what is regarded as his masterpiece, The Best and the Brightest, about the brilliant but blind men who led us into the fiasco of that unwinnable war. He went on to write 20 non-fiction books on politics, sports, business and social history. I think The Fifties, his re-examination of the supposedly bland Eisenhower years, contains all the virtues and vices of his work: outsized ambition and pit-bull reporting shackled to prose that’s both sprawling and clunky. Like so many writers with big reputations and egos to match, Halberstam never got the tough editor he needed.

Halberstam made his mark by winning the Pulitzer Prize in 1964 for his reporting in the New York Times that questioned the veracity of the men leading America’s war effort in Vietnam. Eight years later he published what is regarded as his masterpiece, The Best and the Brightest, about the brilliant but blind men who led us into the fiasco of that unwinnable war. He went on to write 20 non-fiction books on politics, sports, business and social history. I think The Fifties, his re-examination of the supposedly bland Eisenhower years, contains all the virtues and vices of his work: outsized ambition and pit-bull reporting shackled to prose that’s both sprawling and clunky. Like so many writers with big reputations and egos to match, Halberstam never got the tough editor he needed.

The book he was working on when he died, The Glory Game, was completed by Frank Gifford, who played for the Giants in that 1958 title game. It was published – “by Frank Gifford with Peter Richmond” – a year after Halberstam’s death.

Doug Marlette (1949-2007) – Doug Marlette, the Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist and creator of the popular comic strip “Kudzu,” published his first novel in 2001. The Bridge spins around the violent textile mill strikes in North Carolina in the 1930s, in which Marlette’s grandmother was stabbed with a bayonet. The novel is set in the fictional town of Eno, loosely modeled on Hillsborough, N.C., the hot house full of writers where Marlette was living when he wrote the book. When Marlette’s neighbor, the writer Allan Gurganus, read the novel in galleys, he saw a little too much of himself in the composite character Ruffin Strudwick, a gay man who wears velvet waistcoats and sashays a lot. Gurganus called the publisher and demanded that his name be removed from the book’s acknowledgements. A bookstore cancelled a reading, charging Marlette with homophobia, and Hillsborough became the scene of a nasty literary cat fight between pro- and anti-Marlette camps. People who should have known better – a bunch of writers – had forgotten Joan Didion’s caveat: “Writers are always selling somebody out.”

Doug Marlette (1949-2007) – Doug Marlette, the Pulitzer Prize-winning cartoonist and creator of the popular comic strip “Kudzu,” published his first novel in 2001. The Bridge spins around the violent textile mill strikes in North Carolina in the 1930s, in which Marlette’s grandmother was stabbed with a bayonet. The novel is set in the fictional town of Eno, loosely modeled on Hillsborough, N.C., the hot house full of writers where Marlette was living when he wrote the book. When Marlette’s neighbor, the writer Allan Gurganus, read the novel in galleys, he saw a little too much of himself in the composite character Ruffin Strudwick, a gay man who wears velvet waistcoats and sashays a lot. Gurganus called the publisher and demanded that his name be removed from the book’s acknowledgements. A bookstore cancelled a reading, charging Marlette with homophobia, and Hillsborough became the scene of a nasty literary cat fight between pro- and anti-Marlette camps. People who should have known better – a bunch of writers – had forgotten Joan Didion’s caveat: “Writers are always selling somebody out.”

Marlette produced a second novel, Magic Time, in 2006. After delivering the eulogy at his father’s funeral in Charlotte, N.C., Marlette flew to Mississippi on July 10, 2007 to help a group of Oxford High School students who were getting ready to stage a musical version of “Kudzu.” The school’s theater director met Marlette at the airport. On the way to Oxford, the director’s pickup truck hydroplaned in heavy rain and smashed into a tree. Marlette was killed at the age of 57. He was at work on his third novel when he died.

Jeanne Leiby (1964-2011) – In 2008 The Southern Review named a woman as editor for the first time since Robert Penn Warren and Cleanth Brooks founded the literary journal at Louisiana State University in 1935. The woman was Jeanne Leiby, a native of Detroit who had published a collection of short stories called Downriver, set in the corroded bowels of her post-industrial hometown. Her fiction had appeared in numerous literary journals, including The Greensboro Review, New Orleans Review and Indiana Review. Leiby had also worked as fiction editor at Black Warrior Review in Alabama and as editor of The Florida Review before taking the job at The Southern Review.

Jeanne Leiby (1964-2011) – In 2008 The Southern Review named a woman as editor for the first time since Robert Penn Warren and Cleanth Brooks founded the literary journal at Louisiana State University in 1935. The woman was Jeanne Leiby, a native of Detroit who had published a collection of short stories called Downriver, set in the corroded bowels of her post-industrial hometown. Her fiction had appeared in numerous literary journals, including The Greensboro Review, New Orleans Review and Indiana Review. Leiby had also worked as fiction editor at Black Warrior Review in Alabama and as editor of The Florida Review before taking the job at The Southern Review.

On April 19, 2011, Leiby was driving west on Interstate-10 near Baton Rouge in her 2007 Saturn convertible. The top was down and she was not wearing a seat belt. When she tried to change lanes she lost control of the car and it hit a concrete guard rail and began to spin clockwise. Leiby was thrown from the car and died later at Baton Rouge General Hospital. She was 46.

At the time of her death Leiby was, by all accounts, performing masterfully at a thankless job. Due to punishing state budget cuts, she had slimmed The Southern Review down, cancelled some readings and other events for the journal’s 75th anniversary in 2010, and ended the annual $1,500 prizes for poetry, non-fiction and fiction. She did all that without a falloff in quality. She was also working to merge The Southern Review with the LSU Press.

In a conversation with the writer Julianna Baggott, Leiby confided that during her job interviews at The Southern Review she’d offered her opinion that the journal had gotten stodgy and that it was too Old South and too male. One of the first things this woman from Detroit did after she got the job was to lower the portraits of her predecessors – all men – because she thought they were hung too high.

Don Piper (1948 – ) – Don Piper might be the most intriguing person on this list. He died in a car crash – then came back from the other side to write a best-seller about the experience.

On Jan. 18, 1989, Piper, a Baptist minister, was driving his Ford Escort home to Houston after attending a church conference. It was a cold, rainy day. As he drove across a narrow, two-lane bridge, an oncoming semi-truck driven by a trusty from a nearby prison crossed the center line and crushed Piper’s car. When paramedics arrived at the scene, Piper had no pulse and they covered his corpse with a tarp. Since I can’t possibly improve on Piper’s telling of what happened next, I’ll give it to you straight from his book, 90 Minutes in Heaven:

On Jan. 18, 1989, Piper, a Baptist minister, was driving his Ford Escort home to Houston after attending a church conference. It was a cold, rainy day. As he drove across a narrow, two-lane bridge, an oncoming semi-truck driven by a trusty from a nearby prison crossed the center line and crushed Piper’s car. When paramedics arrived at the scene, Piper had no pulse and they covered his corpse with a tarp. Since I can’t possibly improve on Piper’s telling of what happened next, I’ll give it to you straight from his book, 90 Minutes in Heaven:

Immediately after I died, I went straight to heaven… Simultaneous with my last recollection of seeing the bridge and the rain, a light enveloped me, with a brilliance beyond earthly comprehension or description. Only that. In my next moment of awareness, I was standing in heaven. Joy pulsated through me as I looked around, and at that moment I became aware of a large crowd of people. They stood in front of a brilliant, ornate gate… As the crowd rushed toward me, I didn’t see Jesus, but did see people I had known… and every person was smiling, shouting, and praising God. Although no one said so, I intuitively knew that they were my celestial welcoming committee.

Piper recognized many people who had preceded him to the grave, including a grandfather, a great-grandfather, a childhood friend, a high school classmate, two teachers and many relatives. His story continues:

The best way to explain it is to say that I felt as if I were in another dimension… everything was brilliantly intense… (and) we began to move toward that light… Then I heard the music… The most amazing sound, however, was the angels’ wings… Hundreds of songs were being sung at the same time… my heart filled with the deepest joy I’ve ever experienced… I saw colors I would never have believed existed. I’ve never, ever felt more alive than I did then… and I felt perfect.

Alas, perfection was not destined to last. A fellow preacher had stopped at the scene of the accident to pray. Just as Piper was getting ready to walk through the “pearlescent” gates and meet God face-to-face, the other minister’s prayers were answered and Piper, miraculously, rejoined the living. This, surely, ranks as one of the greatest anti-climaxes in all of Western literature. Nonethless, 90 Minutes in Heaven, published in 2004, has sold more than 4 million copies and it has been on the New York Times paperback best-seller list for the past 196 weeks, and counting.

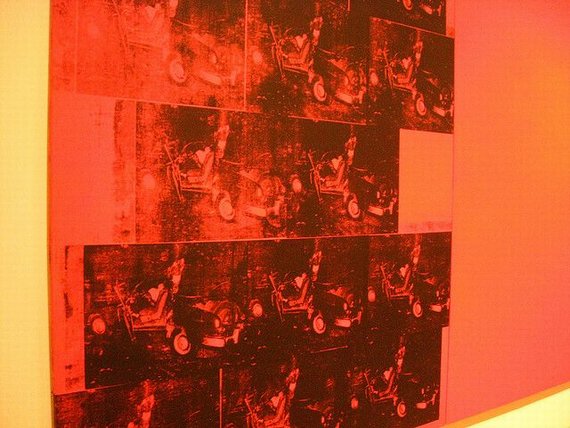

(Image: Orange Car Crash – 14 Times from eyeliam’s photostream)