The author, in earlier years.

There was an era of malls—golden age or dark, I couldn’t say—when they were one-story and off-white in color and anchored by outfits such as Sears and Montgomery Ward and were swarmed by shiftless teenagers in baggy garb rather than fashionable teenagers in snug garb. Okay, dark age. The food court had no sushi. Each and every mall, even if you went on vacation to Memphis or Washington DC, had an Orange Julius. Spencer Gifts and Chess King. Remember? Macy’s was still a tourist attraction in New York City. Nordstrom we’d never heard of at all. Instead of a Cheesecake Factory, there was a Piccadilly. Usually a Regis hair place and an arcade and a Ritz Camera. And instead of a cavernous, luxurious, afternoon-sucking Borders or Barnes & Noble, there was a drab bookshop tucked away in a deserted corner of the mall that bore one of two names, either Waldenbooks or Bookland, and in the mall I grew up near in New Port Richey, Florida it was Waldenbooks. I can still smell the place, like permanent dust and spanking new magazines. In the back of the store there was a hint of break-room odor, and at the front you could whiff the German food from the Schnicklefritz next door. And I can remember what it felt like to lurk in the aisles, HUMOR, SELF-HELP, too tall to stay fully hidden, wanting to be ignored and usually succeeding, wanting to be a common ill-natured loiterer like every other kid at Gulf View Square Mall.

It was around 10th grade that I fell out of love with playing sports. I suffered a loss of competitive vigor. Part of it must’ve been that I was getting lankier while the other guys were getting quicker, but I’d also gotten everything I could out of camaraderie, was all teamed out, spiritless. Since I could walk, I’d been winning big and losing big and settling for ties and each of those results now seemed as good as the others. I was getting beaten out for starting spots on multiple rosters and it wasn’t bothering me near to the degree it should’ve. I started wandering off by myself for lunch, which was a fairly dramatic move. I’d sit against a wall in a quiet courtyard, missing news and jokes and the births of nicknames, and occasionally an assistant coach from one of the teams I’d recently quit would wander by and shake his head at me. I worked up to going missing from my friends for whole weekends. I began to enjoy being a loner, the practice of it and the theory. I could see myself in the role, like an actor getting excited about a script. Without wholesome, scorching afternoon practices to weary me, I began staying up later and later at night, and since these were the days before kids had flat-screen TVs and laptops and gaming systems, what happened was I wound up reading. I don’t remember what. I stopped exercising and stopped laughing and started reading. Maybe the Bible. Every house had one, full of the best stories ever written. Whatever it was, it kept me up long enough that I would sleep during my first couple classes the next morning, forehead against the slick wood of the desk. When the teachers got onto me I didn’t know what to say. It was better to let everyone think I’d smoked a fat bowl before morning bell than to let on that I was wiped from bookworming till the wee hours. I’d never thought one way or another about reading, but now I wanted words rushing through my mind, wanted flipping pages. I relished slipping the bookmark into the middle of a hefty volume. I enjoyed looking up from a passage and squinting pensively. Reading was always something I’d done because it was assigned, something to be rushed through, to be tolerated, much like long-division or mowing the lawn. As was being alone. As was thinking. Now I saw the intrigue. And hey, I had thoughts. Some of them were even my own. And hey, reading helped me have better thoughts. And that had to be valuable for some reason, didn’t it, the ability to conjure high-quality thoughts?

It was sudden. In a couple months I went from gregarious athlete to surly insomniac scholar. That can happen at that age, a persona that’s been simmering under the surface can all of a sudden boil over, but where I was from the standard shift went from athlete to delinquent, from nerd to delinquent, from conceited prep to delinquent, from aspiring redneck to delinquent, etc. People read to children. Old people read newspapers. Middle-aged women probably read tales of romance. But for able-bodied young men, seeking obscure knowledge for the hell of it didn’t really compute. Delinquency computed in a way reading for pleasure never could—vandalism for instance, it made sense. Still does. Worse, what I was doing didn’t, to me, feel like pleasure. I enjoyed it, but not exactly. It was more than that. I wasn’t reading for a diversion. It was a compulsion.

In time I ran through everything in the Brandon house, which wasn’t a whole lot, leaving me, what, the library at the high school? 1) I wanted to have less to do with school, not more. 2) There must’ve been books too dark or vulgar to be included in River Ridge High School’s paltry collection. 3) Like all teenagers, I had trouble keeping up with and returning things I borrowed. 4) I hardly wanted people to know I was reading at all, much less have a record of what I was reading. Last) I found that I wanted to own the books. I wanted the bound, physical objects. I wanted to hide them away in my closet. I liked how they felt in my hands. I’d stack them up like flat trophies and then I’d pull them all out and handle them and restack them in a different configuration. I’d get right down there on the floor with them. It calmed me, when I was away from home, to think of them. Only problem was, I didn’t have enough. They had to come from somewhere, books, and if you weren’t going to borrow them then you had to buy them. Or did you?

The first time was nerve-racking, a rush, but by the third book I was already settling in. My browsing time shortened. My forehead didn’t sweat. I feared getting caught not because I was committing a punishable crime, but because I was committing a strange and possibly subversive act, because getting caught would force me to explain, to divulge my secret self. But the fear didn’t last. I saw pretty quickly that Waldenbooks had not sprung for a security system and that the junior college kid messing with his empty chain wallet behind the counter had precious little interest in protecting his employer’s stock. Nobody expected anyone to steal books. The books were needed to take up the rest of the retail space, because there weren’t enough magazines. The books weren’t expected to move. So I would drift about and zero in on a title, selecting based on God-knows-what and sometimes not even taking a glance inside, slip the volume down the front of my pants, billow my T-shirt a bit so no sharp corners would show, then stroll stiffly out of the Waldenbooks, my blood perking as I passed into the mall proper. Fifty yards to get outside, sometimes with a lethargic but continually suspicious mall cop nearby, then fifty more yards and I was lost in the steamy parking lot, traipsing through drifts of dead palm fronds. The hardbacks were tougher, and the thick old classics, but nobody was watching. Nobody cared. I could’ve walked out with the books balanced on my head. There were kids in other parts of the mall swiping watches, peddling drugs, setting things ablaze, beating other kids up.

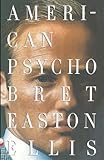

I had no dependable system for choosing a book and no one to ask. Sometimes, naturally, the ones with dashing covers. Sometimes sports books; I didn’t want to participate anymore, but I didn’t mind reading about sports. Stand-up comedians were big then, and a lot of those guys had books out, but I always felt empty returning to the seclusion of my room with nothing but a bunch of jokes. I didn’t have the wherewithal to consider that I might be a budding writer, that I might be swallowing up all available prose in order to learn to produce it, but I knew I wanted to read things I couldn’t fully comprehend. I wanted my head to swim. I wanted to aspire to grasp. And if that’s what you want, to be mired, Nietzsche is a great place to start. I ran through old Friedrich’s whole catalog, because Waldenbooks carried it right there in the one-shelf PHILOSOPHY section and because he was from another country and another time and had a mustache to prove it. I understood a tenth of what he was getting at, but I read every word. I read Cormac McCarthy and couldn’t get into it and now I see I was too green to appreciate him. I read Dickens and I couldn’t believe a person could make up such wonderful lies and I still can’t believe how good Dickens is. I burned through Kerouac, planting the seeds of a wanderlust that would, years later, burst up into the light and run my life. I took down Hemingway one famously terse page at a time and was refreshed and was pleased to be male. I stole American Psycho because of the title and saw that anything went, so long as you didn’t flinch. And there were an equal number of duds. The books on Satanism, for instance, which taught me that matters of the dark underworld generally lose their nefarious mystique when systemized into chapters and paragraphs and sentences and sold as a trade paperback. Also liable to be boring when read about instead of participated in: brewing beer, city planning, massage. Even lesbianism, if you get hold of the wrong sort of book. But I kept every single one. The books took up more and more of my closet and my parents, who I assumed appraised my room from time to time when I wasn’t home, were polite enough not to ask about them.

I had no dependable system for choosing a book and no one to ask. Sometimes, naturally, the ones with dashing covers. Sometimes sports books; I didn’t want to participate anymore, but I didn’t mind reading about sports. Stand-up comedians were big then, and a lot of those guys had books out, but I always felt empty returning to the seclusion of my room with nothing but a bunch of jokes. I didn’t have the wherewithal to consider that I might be a budding writer, that I might be swallowing up all available prose in order to learn to produce it, but I knew I wanted to read things I couldn’t fully comprehend. I wanted my head to swim. I wanted to aspire to grasp. And if that’s what you want, to be mired, Nietzsche is a great place to start. I ran through old Friedrich’s whole catalog, because Waldenbooks carried it right there in the one-shelf PHILOSOPHY section and because he was from another country and another time and had a mustache to prove it. I understood a tenth of what he was getting at, but I read every word. I read Cormac McCarthy and couldn’t get into it and now I see I was too green to appreciate him. I read Dickens and I couldn’t believe a person could make up such wonderful lies and I still can’t believe how good Dickens is. I burned through Kerouac, planting the seeds of a wanderlust that would, years later, burst up into the light and run my life. I took down Hemingway one famously terse page at a time and was refreshed and was pleased to be male. I stole American Psycho because of the title and saw that anything went, so long as you didn’t flinch. And there were an equal number of duds. The books on Satanism, for instance, which taught me that matters of the dark underworld generally lose their nefarious mystique when systemized into chapters and paragraphs and sentences and sold as a trade paperback. Also liable to be boring when read about instead of participated in: brewing beer, city planning, massage. Even lesbianism, if you get hold of the wrong sort of book. But I kept every single one. The books took up more and more of my closet and my parents, who I assumed appraised my room from time to time when I wasn’t home, were polite enough not to ask about them.

Predictably, when I got to college I started stealing more than books. I started stealing groceries and cigarettes and whatever else I needed. Clothes. CDs. I stole a full bottle of booze out from behind a crowded bar—no shit. Still the books too, but college was different. Other people were reading. It didn’t set you apart. There were circles in which reading was cool even. I was becoming aware that one could write as a career, that I could, and was identifying myself publicly as someone who wished to do so. I declared as an English major and all. I put my books on shelves, prominently displayed in my apartment. Big, soft reading chair. A relationship with coffee. There existed girl English majors, and they liked to read. I got glasses, though I barely needed them. I had always known things would be better once I left New Port Richey, and I was right. And if things were this good here in Gainesville, imagine Atlanta or, say, New York City.

The time came to write, to go ahead and attempt to create original fiction rather than to settle for owning books and wearing think-framed spectacles and a long coat and projecting a diffuse and unfounded superiority. So stealing, at that point, became something I did only to avoid paying for things. It was annoying, parting with the little spare cash I had, and hey, I’d developed a skill. I couldn’t write yet but I could steal. The old story: I got too cocky and comfortable and ended up getting caught. I was trying to lift some sort of phone accessory that’s likely obsolete by now, a $6 item. Wal-Mart. They don’t mess around. A real cop with a real gun. Cuffs. Read my rights. They took me down to the county lockup where I had to wait a couple hours in a crowded holding tank and then a couple hours in a cell by my lonesome. They gave me that shot that tests for TB and served me a meal I didn’t eat. I had to pay to get bailed out. So much for saving money.

Maybe I wasn’t wise but I wasn’t hardheaded. I knew getting arrested spelled the end of my stealing days. It was good I’d been thrown in jail for the afternoon. It worked, scared me straight. I started cooking at home, which was cheaper than eating subs and chicken wings. I didn’t need any more clothes. I could borrow music. My classes were piling on all the reading I could handle, and my scholarship paid for those books. My girlfriend at the time was thoroughly, thoroughly unimpressed with my getting nabbed for petty theft at a big-box discount store, and her firm and disgusted declaration that I would no longer be shoplifting anything from anywhere on penalty of losing her also helped seal the decision to give up my old hobby.

One thing, though. I had to go out with a victory. Here came that competitiveness that had abandoned me in 10th grade. I could not stand being chased off by the retail establishment without even a parting shot. I decided to go back to my roots: books. I made a special trip to the Barnes & Noble on Archer Road and said hey to the sharp-haired clerks and browsed the sale books and the audio books and even the blank journals with their felt and paisleys. I took a pass out of habit at LITERATURE and then drifted into the center of the store, MUSIC, and I chose a three-inch-thick biography of Beethoven, the composer’s outsized and wild head on the cover, and I shoved that sucker down under my waistband and walked straight-backed and breezily out the front doors. I felt a comfort in all I’d gotten for free, but also a sadness at the battle ending. I was grateful for how broad the world had become due to those hundreds upon hundreds of books, grateful even to have come from a world small enough that I’d had no choice but to push it open, grateful to have been steeled by all those long nights spent with ill-gotten bestsellers and treatises and ghost-written autobiographies and religious narratives and horror anthologies and Victorian epics and even works of German philosophy, reading in what felt like secret—reading, it seemed, against something.

Post Script:

For seven years, during my late twenties and early thirties, all my books sat with stoicism in a storage unit in Spring Hill, Florida, under desk chairs and VCRs and a fake Christmas tree, in a metallic building pumped with conditioned air. The books had to wait for me to live in one place long enough that I’d retrieve them and creak them open once more. That place turned out to be Oxford, Mississippi. I’ve been here for two years, one of countless writers the town has collected. I finally drove down to Florida last month and hauled my literary possessions in faded green bins up to my apartment under the Dixie sun and a little unconvincing Dixie rain too, then I sat in my office and picked each book up and looked it over and tried to remember which store it had come from. I didn’t feel much for the books, just garden-variety nostalgia. No way to tell if the feeling was pleasant or demoralizing; that’s the way with nostalgia. I set each book in one of two stacks based solely on the merit of its content, one for keepers and one for books to be liquidated. It had once felt like rebellion to acquire the books and now it felt like rebellion to get rid of them. Just last week I took the lot to be sold up to our local bookstore, Square Books, and just this morning I received my cash. I opted for the lesser amount of cash over the greater amount of store credit because cash is cash and credit, in this case, is more books. And I plan to spend the cash this weekend on baby supplies and office supplies and oysters and beer.

End of story.