1.

It was late January 2009, and I hadn’t read the news in days. It felt like a wound. In the basement of the Lighthouse Hotel in Galle, Sri Lanka, the business centre was dark. I sat back in my chair, staring at a white computer screen, which was nearly the only light in the room.

My inbox has always offered me an American volume and variety of information no matter where I open it. That night it was full of what was going on in other parts of Sri Lanka, a country in which my parents were born, and I was not. About five hundred kilometers north of where I was a guest at the Galle Literary Festival, the Sri Lankan Army was fighting the separatist Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam.

People were dying in this war—among them, unarmed civilians caught between the warring parties. I knew it; I had arrived knowing it. And they were mostly Tamils. I am Tamil. The hollow curve of nothingness inside me sharpened to a point: I missed home with something bordering on pain or hunger. Home was a place where people would have talked about this openly.

And what was this place? Wasn’t this festival also a place where we made space for important subjects? After some consideration—how empty was the room? how empty did I feel?—my eyes swam. I recalled, as though it had been years rather than minutes, the top floor of the hotel, where I had just left a group of readers and writers talking to one another. The night’s insistent, pulsing beauty. Their voices persisting, the conversation moving through the air by the sea.

2.

Prior to this year’s Galle Literary Festival, which was held last month, I saw that Arundhati Roy, Noam Chomsky, and some other writers were calling for an authors’ boycott of the event through an appeal publicized and supported mainly by the French NGO, Reporters Without Borders.

“We believe this is not the right time for prominent international writers like you to give legitimacy to the Sri Lankan government’s suppression of free speech by attending a conference that does not in any way push for greater freedom of expression inside that country,” their statement said. They cited the unsolved murder of Lasantha Wickrematunge, a prominent newspaper editor, which had happened mere days before my 2009 arrival in Sri Lanka. They also emphasized the disappearance of a cartoonist, Prageeth Eknaligoda, whose work was critical of the government. They cited the deaths and disappearances of a number of other journalists as a justification for their call to writers to disengage with the literary festival.

It is true—and bears repeating—that threats to media freedom and freedom of expression in Sri Lanka have largely met with impunity. To say this horrifies me would be an understatement.

But it is not true that the Galle Literary Festival is “a conference that does not in any way push for greater freedom of expression inside that country.” Yes, in the room the women come and go, talking of Michaelangelo. But the room itself—the room itself is very important. Talking about writing, art and ideas can be quite a serious business, one that is all the more necessary as freedom of speech is threatened, as writers censor themselves or disappear.

3.

What is it that a literary festival does? Since my book came out in 2008, I have been to a number of them; we talk about books and art and life, and people seem, for the most part, happy.

I was unhappy that night in Galle when I read the news, but I did not begrudge my fellows the happiness of the festival, its victory of joy and art and conversation and ideas in this place that like any other place, deserved and deserves to talk and sing and laugh. Happiness is not an offense against the unhappy, and happiness, too, can be an act of resistance. Happiness is not necessarily a light or unconsidered thing.

To read, to write, to talk: these are small acts of valiance—though certainly not the only ones—in a country where some have died for words, for art. We create and consume art to gain a deeper understanding of ourselves and others. So why would you defend freedom of speech by suggesting that people stop talking?

And yet putting people in a room together is not enough either. These people must choose to walk toward each other and have real conversations. This is hard anywhere, but especially in an environment where freedom has been threatened. “Only connect,” E.M. Forster wrote. Writers tend to think of this in terms of craft, but hold it up for a moment, and let the light shine through: it’s a political statement. If you have that room, what will you do with it?

4.

Don’t show up for the literary festival and this will never happen to you:

I wander through a crowd at the festival, and a man pauses before me. He is older than me, and has glasses. An uncle, albeit the kind who is not related.

You’re the author of Love Marriage.

I nod.

I’m Tamil, from Jaffna, he said. It’s good to see you here.

If you do not go, you will not meet the reader who has been waiting for this conversation with you. Who has questions for you. And you will never realize that you were waiting for him too, with your own questions, with the ever-unfurling scroll of the things you don’t know.

5.

If a country stops people from speaking and no one is there to witness it, does it make no sound?

6.

Meet my students in Galle, where I taught a workshop. The oldest student might have been in his fifties, and the youngest, a girl with skin as smooth as milk, was perhaps as young as ten. I had given them something to read—the short story “The Things They Carried,” by Tim O’Brien. They looked and looked and looked at the things people carry with them as they move through conflict. We talked about war and metaphor and burdens and gifts and choice and memory and love.

At the end of the class, the girl pressed her lips to my cheek. Thank you, she said shyly. She spoke English with a Sinhalese accent and was from the Colombo neighborhood of Cinnamon Gardens. Her older brother smiled at me.

If I met them on a street in Colombo I think I would know them, the almost indescribable sweetness of their faces, their good intentions, their unpretentious love of words, and their deep-hearted openness to the places words could bring them, although they were children, and what the story had shown them was both horrible and beautiful.

7.

“What they carried,” they read, “varied by mission.”

8.

I carried the book I had written, which is about a Sri Lankan family that lives inside and outside of Sri Lanka, and its daughter, who must learn her forebears’ political pasts and decide her own future.

I carried the character of Kumaran, a Tamil Tiger, who belongs to this family, who is dying, and who regrets parts of his life even as he remembers wrongs that have befallen him. I carried his siblings, his daughter, his friends, his enemies, and the lives I had imagined for them. The thousand empathies I had tried to invent. I carried what people had said about the book being wrong, or untrue, or tilting too far or unfairly one way or another. I carried letters from people who believed in it, who told me they loved it. I carried my fear. But I went. And people asked me about the story I had written.

9.

“We ask that by your actions you send a clear message that, unless and until the disappearance of Prageeth is investigated and there is a real improvement in the climate for free expression in Sri Lanka, you cannot celebrate writing and the arts in Galle,” says the Reporters Without Borders statement.

Let me tell you about one of the first books I loved. It is called Funny Boy, and its author, Shyam Selvadurai, curated this year’s Galle Literary Festival. Funny Boy is about a young gay Tamil boy coming of age in the late 1970s and early 1980s in Sri Lanka; it ends with a brutal depiction of the 1983 anti-Tamil riots, a staggering spate of violence in which the government was complicit and in which thousands died.

Let me tell you about one of the first books I loved. It is called Funny Boy, and its author, Shyam Selvadurai, curated this year’s Galle Literary Festival. Funny Boy is about a young gay Tamil boy coming of age in the late 1970s and early 1980s in Sri Lanka; it ends with a brutal depiction of the 1983 anti-Tamil riots, a staggering spate of violence in which the government was complicit and in which thousands died.

In one chapter of the book, a journalist goes missing. I won’t tell you what happens to him. You should read it for yourself. You should celebrate this book, which I respect and admire, and think you would too.

10.

Dear Reporters Without Borders: You can’t possibly be saying that talking about art isn’t a political act! But say whatever you want to say. I promise to show up, and to defend your freedom of speech by being one of those who wants to speak to you.

“We ask you in the great tradition of solidarity that binds writers together everywhere, to stand with your brothers and sisters in Sri Lanka who are not allowed to speak out,” Reporters Without Borders says.

To those who would have writers from abroad stop going to Sri Lanka: I refuse to disappear. If my brother vanishes, is it an act of solidarity for me to leave the place where he was lost? When I have the ability to be there?

The great traditions of solidarity are built on conversation, long and careful study and thought, and yes, informed travel of the mind and body—not the petition of a moment. This is a long engagement, and must emphasize serious exchange—something that has no chance of happening if the door is closed.

Invite me to Galle again. I’ll go. Let my eyes swim. Let the talk waft around me; it may not be perfect or entire, but it will be ours, and I want to listen to it go as far as it can, to be one of the people who walks toward other people rather than away. I will meet you, my friend, by the ocean; this is solidarity because you will tell me about your place, and I will tell you about mine.

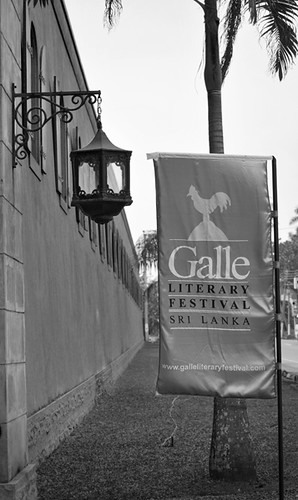

Image used with permission of Galle Literary Festival Sri Lanka