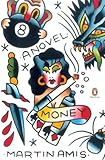

A few weeks ago I ventured into the English Faculty Library at the University of Oxford to borrow a work of fiction. A friend had recommended the novel Money: A Suicide Note, by Martin Amis, and for a variety of reasons the only library from which I could borrow one of the University’s 15 copies was the English Faculty. (All but two of the copies were owned by college libraries—none my own, and colleges do not lend to non-members—or by libraries that do not permit borrowing to anyone. The second circulation copy was out.) Although my subject is History and Politics, the English Faculty does permit non-members to borrow from its collection, but with some rather curious reservations.

A few weeks ago I ventured into the English Faculty Library at the University of Oxford to borrow a work of fiction. A friend had recommended the novel Money: A Suicide Note, by Martin Amis, and for a variety of reasons the only library from which I could borrow one of the University’s 15 copies was the English Faculty. (All but two of the copies were owned by college libraries—none my own, and colleges do not lend to non-members—or by libraries that do not permit borrowing to anyone. The second circulation copy was out.) Although my subject is History and Politics, the English Faculty does permit non-members to borrow from its collection, but with some rather curious reservations.

When I presented the volume to be checked-out, the librarian examined my card (which discloses my subject), pursed her lips, pressed her palms protectively over Martin’s image on the dust jacket, and clearly made herself ready to say something that she regarded as unpleasant:

Librarian: “Are you reading this book just for pleasure?”

Me: “Well, I suppose, not entirely…”

Librarian: “Because you know some people may be studying this for a course or an exam.”

Me: “Well, um, even in the summer?”

Librarian: “Oh, perhaps not, but we really don’t like to lend just for pleasure reading. That’s not what these books are for.”

To be fair, my responses were even less coherent than what this paraphrase suggests, which may be why the librarian did not offer much compelling justification for her reluctance to share the work of the younger Amis. (No doubt Martin’s father, Sir Kingsley Amis, descended from solid Wodehousian stock, would have pipped me to the riposte, but despite my meagre performance I was permitted, in the end, to borrow the book.) For one thing, surely no English student, when deprived of a sought-after volume, would find any consolation in the knowledge that their degree was being sacrificed at the altar of a D.Phil. dissertation, rather than merely for my pleasure. It might be said that if non-English students were prevented from borrowing, the chances of any volume being available would increase, but this ignores both the curious tendency for all students to equate borrowing books with reading books (thus drawing perverse and prolonged comfort from the mere presence in their bedroom of the volumes on the reading list), and the academic equivalent of a mutually-assured destruction, the threat that other faculties will impose reciprocal bans on non-members and thereby obliterate each and every Dreaming Spire.

It is no small irony that the work at issue was by Martin Amis, one of the University’s most precocious children. Amis read English at Exeter College in the late 1960s and took a “Congratulatory First,” a title bestowed by examiners at an undergraduate’s viva (oral defence, now defunct), telling the student how much they enjoyed reading his examination scripts. Amis is renowned for his command of, and appreciation for, the English language, which he deploys to dark and hysterical effect in The Rachel Papers, Dead Babies, Success, and the aforementioned Money. While it is difficult to imagine Amis himself taking anything like a diminutive view of reading just for pleasure, there remains much to be said in defence of other readers, who react more moderately to a thoughtful turn of phrase, or for whom Milton may do just as well as a glass of warm milk before bedtime— in short, The Millions of us who read just for pleasure—and why these might not be so readily turned away from the circulation desk.

At the same time I was reading Money, I was (and still am) working through the collected works of Lewis H. Lapham, editor emeritus of Harper’s Magazine, in preparation for an interview in late September. While more recently remembered for his eloquent, sharp, and (at the time) lonely criticism of the Bush Administration after September 11, 2001 (collected in Theater of War, Gag Rule, and Pretensions to Empire), Lapham’s earlier writing considered the existence of an American aristocracy (what he calls an “equestrian class”), and the enervating effects of a culture worshipful of money. Lapham published Money and Class in America in 1988, which could be described as a non-fictional explanation of the world Amis depicts in Money, which was published in 1984, and over half of which takes place in New York City, where Lapham also resides. While John Self, the protagonist in Money, is certainly not a member of Lapham’s equestrian class, it is not difficult to imagine Lapham nodding grimly as he reads of Self’s destructive attempts to ape his betters:

I have money but I can’t control it: Fielding keeps supplying me with more. Money, I think, is uncontrollable. Even those of us who have it, we can’t control it. Life gets poor-mouthed all the time, yet you seldom hear an unkind word about money. Money, now this has to be some good shit.

Or, perhaps not, and instead we should feel, after reading Amis, that:

The irony which at first made one smile, the precision of language which was at first so satisfying, the cynicism which at first was used only to puncture pretension, in the end come to seem like a terrible constriction, a fear of opening oneself up to the world.

This is how a former professor of English at the University of Oxford described the work of Amis and other of his British contemporaries (including Ian McEwan and Salman Rushdie) in a newspaper article published the very same week that I was wondering whether to include a question about Amis in my interview with Lapham. While it is tempting to view with awe and wonder such a web of meaning and connection, spinning-up as if from nowhere as the literary stars align, in fact the effect is nothing more banal than seeing a new friend all around town: before being introduced, you just didn’t think to notice.

Those who are at all familiar with Lapham’s prose will appreciate this point especially, recalling his preference for historical, cultural, and literary allusion. Lapham’s essays are a study in the art of the “almost tell,” meaning that his arguments are presented less as Polaroid truths and more as symphonic orations, including the presumption that the audience will withhold any applause until the end of the last movement, and its final judgment until after a good night’s rest and perhaps mulling over the reviews in the next day’s newspaper. The first chapter of Money and Class in America is entitled “The Gilded Cage,” which is the phrase used by Edith Wharton in The House of Mirth to describe the circumstances of New York’s social elite at the beginning of the twentieth century. Lapham elaborates the allusion, intimating that:

Those who are at all familiar with Lapham’s prose will appreciate this point especially, recalling his preference for historical, cultural, and literary allusion. Lapham’s essays are a study in the art of the “almost tell,” meaning that his arguments are presented less as Polaroid truths and more as symphonic orations, including the presumption that the audience will withhold any applause until the end of the last movement, and its final judgment until after a good night’s rest and perhaps mulling over the reviews in the next day’s newspaper. The first chapter of Money and Class in America is entitled “The Gilded Cage,” which is the phrase used by Edith Wharton in The House of Mirth to describe the circumstances of New York’s social elite at the beginning of the twentieth century. Lapham elaborates the allusion, intimating that:

The House of Mirth addresses itself to what in 1905 was an irrelevantly small circle of people entranced by their reflections in a tradesman’s mirror. In the seventy-odd years since Wharton published the novel the small circle has become considerably larger, and the corollary deformations of character show up in all ranks of American society, among all kinds of people caught up in the perpetual buying of their self-esteem.

The literary reference at once illuminates Lapham’s point with the full range of Wharton’s sensibility and refined description, or at the very least the reader is directed to a source of further understanding—provided she remembers to tell the librarian that her visit to Wharton’s Upper East Side drawing rooms is for business, not pleasure.

The specific terms in which the librarian formulated her anxiety—”…some people may be reading this for a course or an exam…”—bespeak something of the insecurity that perpetually darkens the horizon outside the offices of every English faculty, especially during the rainy season otherwise known as the humanities department budgetary review. The appeal is made to a higher purpose—”That’s not what these books are for”—and the hope is that despite having paid our admission to the theme park we will continue to respect the height requirements on the literary roller-coaster, not to mention its place amongst the park’s founding attractions. The irony is that by protecting the importance of the enterprise with the threat of restricted access and the real pain of condescension, the operators put at risk both a life-sustaining custom, and the continued existence of the very thing that they purport to discover:

But I incline to come to the alarming conclusion that it is just the literature that we read for “amusement,” or “purely for pleasure” that may have the greatest, and least suspected influence upon us… Hence it is that the influence of popular novelists, and of popular plays of contemporary life, requires to be scrutinized most closely. (T.S. Eliot, “Religion and Literature,” 1934)

There are other passages from Eliot that bear directly on this subject. In the same essay, Eliot rejects what must be the librarian’s view of the aim of wider reading (“an accumulation of knowledge, or what sometimes is meant by the term ‘a well-stocked mind'”) in favour of what Lionel Trilling might have recognized as The Liberal Imagination, that “very different views of life, cohabiting in our minds, affect each other, and our own personality asserts itself and gives each a place in some arrangement peculiar to ourself.” But to belabour the point with too much critical quotation risks begging the question, and confessing the very thing we are suggesting should be irrelevant, or at least beside the point.

There are other passages from Eliot that bear directly on this subject. In the same essay, Eliot rejects what must be the librarian’s view of the aim of wider reading (“an accumulation of knowledge, or what sometimes is meant by the term ‘a well-stocked mind'”) in favour of what Lionel Trilling might have recognized as The Liberal Imagination, that “very different views of life, cohabiting in our minds, affect each other, and our own personality asserts itself and gives each a place in some arrangement peculiar to ourself.” But to belabour the point with too much critical quotation risks begging the question, and confessing the very thing we are suggesting should be irrelevant, or at least beside the point.

The final explanation for the use of the diminishing modifier “just for pleasure” is lost somewhere in the fog surrounding that overwrought and spectacularly hackneyed phrase “work-life balance.” The circumstances may be less clear when one is studying Plato, John Rawls, or J.R.R. Tolkien, compared to a difficult translation of Greek or Latin, an econometric proof, or an equation in particle physics, but there is only so much time one can or should devote to even academic work. Not only does the law of diminishing returns extend beyond discounted cash flow analyses and the building of brand collages, but like a Blackberry or a conference call, under no circumstances should any of these appear during family dinners, cocktail parties, or on the bedside table.

The problem for the librarian, no less than for the career consultant, the occupational health and safety supervisor, and the beleaguered investment banker, is that the notion of a “work-life balance” is a terrible false dichotomy, the Marxist equivalent of giving all your chips away before the deck is even shuffled and then borrowing from the dealer to buy a round for the table. It is manifestly impossible to divide one’s life into neat or even approximately spherical compartments (how many New York Times crossword puzzles have been completed with a “Eureka!” exclaimed while on the family dog’s midnight promenade), and the decision to deny the obvious is generally employed by those who actually know better, which is why they are forever unsatisfied with the level of the scales. While it is plainly true that one can read a book more or less closely (substitute a beach blanket and a daiquiri for a pencil and a desk), it is equally true that something of everything we read is retained, to be recalled, by chance more often than design, on some or another future occasion, a dinner conversation, a tutorial essay, or a game of Trivial Pursuit. As every student who has written an examination knows all too well, it is impossible to predict when the most felicitous recollections—legend has it, the essential ingredients in the making of a “Congratulatory First”—will occur, but the chances are most assuredly increased in direct proportion to the number of books we read.

Even, just for pleasure.

Image credit: Pexels/Pixabay.