Flavorwire’s list of the Top Ten Bookstores in the US was not supposed to piss me off, but that’s exactly what it did. It was supposed to be the sort of article you read and then forget about until someone else runs it again next year. Instead, being the disagreeable sort, I found myself dwelling on the thing and, well, getting pissed off.

The list angered me for several reasons. For one thing, it began with the obligatory opening gambit, “Bookstores are dying.” This is the default commentary-of-the-moment regarding bookstores (independent or otherwise). It follows from the idea that bookstores, like record stores, will be a thing of the past before you have time to finish Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom. Of course, this line of reasoning assumes that books are just like CDs and that record stores are, indeed, gone. Though neither of these statements is true, I will concede that bookstores are somewhat imperiled at the moment.

The list angered me for several reasons. For one thing, it began with the obligatory opening gambit, “Bookstores are dying.” This is the default commentary-of-the-moment regarding bookstores (independent or otherwise). It follows from the idea that bookstores, like record stores, will be a thing of the past before you have time to finish Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom. Of course, this line of reasoning assumes that books are just like CDs and that record stores are, indeed, gone. Though neither of these statements is true, I will concede that bookstores are somewhat imperiled at the moment.

Okay, maybe there are fewer bookstores in existence now than there were ten or twenty years ago, but to say that bookstores are dying is an oversimplification. It’s not so much that they’re all dying, but that a certain kind of bookstore is on its way out. The closure of the Lincoln Center Barnes & Noble, a superstore, for instance, represents the shifting tide in the book retail world. That store opened in 1995, and as we all know by now, a lot has changed in the media business since then. The days of requiring a 60,000 square foot storefront to sell books are coming to an end, if they aren’t already over. Make no mistake, the B&N closure was an epoch-defining one, even if it was a rent hike that made it happen.

The superstore made a lot of sense in the pre-internet era. In order to offer the largest possible selection, you needed a lot of space. Initially, independent stores like Powell’s in Portland, Oregon and The Tattered Cover in Denver opened huge storefronts carrying tens of thousands of titles. The chain stores – especially Barnes & Noble – mimicked the open space, the big comfy chairs, and the air of bookish intellect of these stores. They took the concept of the superstore national, and in the process, they leveraged their size, scale, and efficiency to secure favorable deals from distributors. In short, they were able to sell books for less, which enabled them to sell more books.

But Amazon and the rest of the ecommerce stores made the issue of selection and scale largely moot. How do you compete with a store that claims to offer every book in print? Still, having a physical location with a lot of books was valuable; if someone wanted the book that day, these stores were there for them, and they offered a large enough selection to satisfy all but the most esoteric needs. But what would happen to these stores if the need for the physical book were suddenly removed? With the rising popularity of ebooks – set to consume anywhere from 15% to 50% of the book market in the next five years, depending on who you believe – we are about to find out the answer to that question.

Barnes & Noble and Borders both know first-hand what it’s like to be suddenly left with a product that no one needs. In the 1990s and early 2000s, both dedicated significant floor space to CDs and DVDs. The book industry even had a term for this – “sidelines,” a term they later revised to the much catchier “non-book products.” But digitization and the internet came quickly for CDs, gutting that business in just a few years. As broadband speeds increase, streaming video will eventually kill off the DVD, as well. In response, the big stores turned to products that couldn’t be so easily digitized. Almost every big store now has a cafe, creating a “third place” where people could congregate and discuss the books and periodicals they’ve purchased. Many stores have converted an area into a permanent events section, giving them a seating capacity that rivals some small theaters and attracting big name authors for readings and parties. A few weeks ago, Borders announced it will be selling custom-made teddy bears in its stores. But despite their best efforts, the large stores face a daunting and dismal future.

Hence the elegiac mood of the Flavorwire piece, and its imploring “buy some books, you lousy ingrates” call to action. Another pet peeve of mine is when people consider their local independent bookstore a charity. Unless your store is a non-profit, it should succeed or fail based on how well it does as a business, not because of noblesse oblige on the part of your municipality. Allowing people to treat your for-profit business like a charity can have some unwanted side-effects. I’ve worked for stores that would occasionally charge admission to a reading. Typically, the price was purchasing a copy of the book, which seemed perfectly reasonable to me – you’re there to see the author, you buy the book, the store makes some money, the author makes some money, everybody wins! But all too often, people would look at me as if I’d just told them air was no longer free. “You shouldn’t be charging for these events,” they’d say. “They’re good for the community.” In other words, they were looking for an evening of free entertainment. Well, this isn’t the library, ma’am. We have to pay the bills somehow.

But despite all of this, there are some reasons to be excited about bookstores. The Flavorwire article came to my attention because of the efforts of two New York City independent bookstores – Housing Works and McNally-Jackson – who had posted the article to their Tumblr blogs. Housing Works pointed out that most of the best indie bookstores in New York had opened in the last ten years, not closed. They were talking about Greenlight Bookstore, WORD, McNally-Jackson, Idlewild, Powerhouse, and Desert Island. In Los Angeles, where we’ve had some substantial bookstore attrition in recent years, several new stores have opened, including Metropolis, Family, Stories, The Secret Headquarters, and the Brentwood Diesel store. On top of that, Vroman’s Bookstore, my former employer, was doing enough business to buy fellow LA indie outpost Book Soup (also a former employer) and Skylight Bookstore expanded, annexing a neighboring storefront.

These stores are succeeding not because they are the biggest stores, but because they are the right stores for their areas. We’re seeing a resurgence of the neighborhood bookstore, something many had considered dead in the heyday of the super stores. Technology has actually leveled the playing field between big stores and small stores; anyone with enough capital and the space for a large copy machine can have a Book Espresso Machine, giving them access to hundreds of thousands of titles, as well as custom-printed books. And web applications like Foursquare and Facebook Locations don’t discriminate between businesses based on size; anybody with a good hook can lure people to their store and capitalize.

Which brings me to the second thing I hated about the Flavorwire piece: What does it mean to say “These are the best bookstores,” after all? Any list that includes Powell’s, The Strand (a store that sells mostly remainders and used books), and Secret Headquarters is comparing apples to BMWs to gym memberships. Making a list like this is akin to asking, “What’s the best place to buy food in Los Angeles?” and then listing Whole Foods, The Cheese Store of Silver Lake, and Animal as your answer. Sure they all sell prosciutto, but that’s more or less where the similarities end.

Please don’t think the stores on Flavorwire’s list aren’t great – they are – but the stores they chose reveal the futility of the whole process. What makes a “great bookstore” and what do the stores on the list have in common with one another, other than that they all sell books? The truth is, I can teach you to write a “Best Bookstore” list right now. Nearly every “Best Bookstore” list pulls five or six stores from the following list of venerable indies: Powell’s, Tattered Cover, Vroman’s, Book People (in Austin, TX), Elliott Bay (Seattle, WA), and Books and Books (South Florida, the Cayman Islands & now Long Island). Those are the remaining indie super stores, and they rightly deserve praise, but there are so many tremendous smaller stores that are equally deserving of recognition. There are too many, in fact, to make a list (Believe me, I tried). And what makes so many of these stores incredible, what many of the chain stores could never mimic, is the staff. A better list might be one that names the top 10 booksellers in America (I could take a crack at that: Stephanie Anderson from WORD, Emily Pullen from Skylight, Michele Filgate from Riverrun, Rachel Fershleiser from Housing Works…Well, I could go on).

In the end, it’s irrelevant, as the only bookstore that anybody cares about is the one near them, the one whose staff knows their tastes, the one that hosts your favorite author when he or she comes to town. For some of you, that’s no doubt a chain store. I grew up outside Syracuse, NY, and I will absolutely shed a tear the day the Borders in the Carousel Center Mall closes, as it was place I remember visiting when I was in high school and just discovering the pleasure of reading. The rest of the stores, though – the big, nationally known bookstores – exist for you, unless you live around the corner from one of them, more as monuments than as businesses. They’re kind of like those iconic bars and restaurants that people make a point of stopping at every time they’re in New York or LA – they’re the McSorley’s or the Musso & Frank’s or the Rendezvous of bookstores. If they went away, you’d read about it in the paper. It would be an “important moment,” but its impact on your life would be minimal unless they are your store. It’s the proverbial store around the corner that you care about, and if that store continues to serve you well, I think it will survive. If it doesn’t, well, hopefully someone will put it on some sort of “best of” list before it goes. Now, if you’ll excuse me, I’m off to celebrate the fact that my local bookstore is still kicking. Maybe you should do the same.

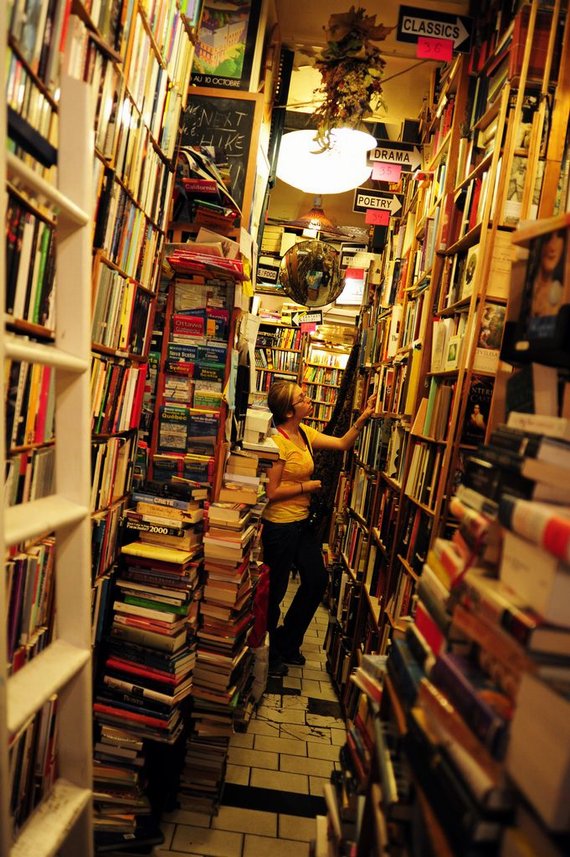

(Image: Abbey Bookstore image from poisonbabyfood’s photostream)