For those who stay abreast of such matters, the last few months of the Atlantic’s forays into fiction have been positively nail-biting. In November, the magazine announced it would be offering a subscription of two stories a month exclusively on the Kindle. As if to quell a possible uprising of the deviceless, they turned around and released the yearly print fiction issue to the entire subscriber base. This June, they’ll convene two panels on the topic of Fiction in the Age of E-books at Toronto’s Luminato Festival—presumably, one hopes, to settle the matter.

For those who stay abreast of such matters, the last few months of the Atlantic’s forays into fiction have been positively nail-biting. In November, the magazine announced it would be offering a subscription of two stories a month exclusively on the Kindle. As if to quell a possible uprising of the deviceless, they turned around and released the yearly print fiction issue to the entire subscriber base. This June, they’ll convene two panels on the topic of Fiction in the Age of E-books at Toronto’s Luminato Festival—presumably, one hopes, to settle the matter.

How far we’ve come since 2005’s dark days, when Atlantic editors winnowed fiction down to a yearly newsstand-only digest! The now-quaint rationale was, “Reporting consumes a lot of space.” But in fiscal year 2009, when book review sections shriveled and houses purged editors and authors alike, dreamy fabulists, note: the Atlantic moved forward to find space for fiction again. And we should watch what they do closely. Because, in the past five years, while other news mags stumbled to find a way to get readers to consume their space—the Atlantic’s so-sensible-it’s-revolutionary strategy has made them a model for how print and online can survive side-by-side.

You may by now have noticed I have a little Atlantic problem. By this I don’t mean I have a problem with the Atlantic. (Though I often have a problem with the Atlantic.) My problem is more along the lines of the New Yorker enthusiast who wallpapers his bathroom with covers, or the public radio supporter who accepts the free tote though clearly informed this has diminished her pledge. Like these other fans, my outlet of choice has passed beyond pastime: it has become manifest as some previously inexpressible part of myself, one best revealed through a convenient duck hat or fashionable messenger bag—though part of the Atlantic’s appeal is that instead of redesigning its tote bags, it convenes a panel discussion.

How well I remember each small but strategic move! First, there was 2006’s “tech” column, in which James Fallows gamely chin-stroked over such wonders as Microsoft OneNote (“What makes some software ‘interesting,’ as opposed to merely usable?”). Next came “Print” and “Send to a friend” options. (Standard now, of course. But they were on it.) They linked subscriber accounts to an online profile, and, when blogging began its rise, immediately hired five famous bloggers—and let them blog.) Harper’s continues to plague us with subscriber-only PDFs—annoying in hard copy, unusable by device—and the New Yorker’s doorstop of a CD-ROM has become a series of clunky scans one must select page-by-page to print. (If one can read the hazy type at all.) Meanwhile, the Atlantic has had its Twain and Nabokov up and accessible to all for years.

Now, while the New York Times futzes around with photo galleries and “followers” and Slate piles still more boxes into its ancient maroon masthead, the Atlantic (excuse me—AtlanticWire) is on its umpteenth web redesign, a go-to online entity that has, if anything, cannibalized the magazine. While bloggers Megan McArdle and Ta-Nehisi Coates crank out high-concept cover pieces, P.J. O’Rourke and critic Mark Steyn, the golden mean of the magazine’s original libertarian readership, have been gently phased out. Welcome to newer hires Sandra Tsing Loh and Caitlin Flanagan—the original Tipsy Belden and Nancy Shrew—who duel it out almost every issue, the better to draw women everywhere by offending all of them.

Immediately hiring bloggers when blogging began its rise seems like an obvious way to stay above water – but it was so obvious almost no one else did it. (See Conde Nast’s Flip.) Until recently, numerous publications that will remain nameless still preferred to push their reporters into blogging rather than hiring reporters who already blog. But the Atlantic has never been saddled with delusions of grandeur. Even their poetry—it’s “poetry”!—rhymes.

Now that e-publishing has hit even the books world with the online equivalent of a sucker punch, I am poised to absorb what the Atlantic sees to come.

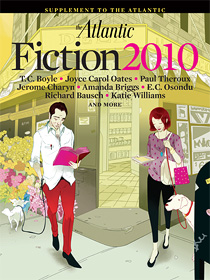

The cover of Fiction 2010 offers, to say the least, a provocative vision. To our left glides a gentleman in pegged red pants holding an honest-to-God—positively florid—paper-and-ink book. To our right saunters a young lady fixed on the lambent square of her Kindle. They are shortly to meet cute—heads bent, dogs lightly leashed—near a mailbox at the corner of Publishing 3.0. The attractive pair is surrounded by blooms, sunlight, even a deli’s beckoning door. Their future is plentiful and bright—and there is not an iPad in sight.

If you are swayed by certain unimpeachable sources, this vision is akin to blasphemy. The New Yorker’s Ken Auletta recently depicted that same future as a battle epic and brutal, the upstart iPad flashing its pretty UI and 60,000 titles against a staid Kindle, its inkless jabs a pathetic defense. Acknowledging that Amazon got a jump by getting Kindles into readers’ hands first, Auletta reasons that device-based argument is nonetheless is limited: “The analogy of the music business goes only so far. What iTunes did was to replace the CD as the basic unit of commerce; rather than being forced to buy an entire album to get the song you really wanted, you could buy just the single track. But no one, with the possible exception of students, will want to buy a single chapter of most books.”

That’s two assumptions, both incorrect. (This is why you don’t listen to writers whose publications slap up stories in teeny Times Roman.) 1) That all readers read alike, and 2) that whatever device prevails will accommodate books—not that books will change to accommodate the device.

Because, while a chemistry textbook or history of Rome must eventually be delivered somehow in entire, readers of fiction have been buying “tracks” of books for centuries. They’re called short stories – coincidentally, exactly the item the Atlantic is currently offering in an exclusive curated series on the Kindle. It’s just a start, but it’s a nod to an important distinction between fiction and other kinds of writing that must hew more closely to their form of delivery. Even poor poetry is hampered by its linebreaks, but fiction is the original mutable source, one that encourages authors to flex their muscles and tackle it in different media, now deliverable anywhere in any form. Forget your weekly Dickens. Fiction in variant array has bloomed on the internet from the beginning, from Darcy Steinke’s blind/spot to Rick Moody’s Twitter story to Japan’s booming mobile-fiction market.

Of course, your average person sometimes likes to just sit in the bathroom and read a real-life book, too. (Kindles don’t play well with the Charmin.) When it came to news, the Atlantic was the first to realize that, though online news would change to accommodate its new host into blog, comment, tweet, and update, that didn’t mean throwing out the baby with the bathwater. This means, when offering fiction, it’s wise to partner with someone who can deliver it in a dog-earable form, too—like, I don’t know, Amazon. “Neither Amazon, Apple, nor Google has experience in recruiting, nurturing, editing, and marketing writers,” Auletta argues. I’m not sure if Auletta has been on Amazon since 1997, but it actually owns every title, reviewer, reader, crank and author online. His claim makes sense only if you define Amazon’s actions against those traditional publishers—and I think even then most authors would tell you their publishers don’t really recruit, nurture, edit or market their writers, either.

I don’t know how the Atlantic, Apple, Amazon, or Auletta’s collected works will fare in the coming years (though they will certainly be called on first in class). But it seems important to check the hype when a newbie goes up against the mightiest bookstore in the land and a publication that’s remained robust in print, set the pace online, all while trying to see how fiction can fit in the mix. Steve Jobs is banking on my wanting to read on a prettier screen. But fictive folks read in different ways, and I don’t mean being able to turn my screen around and have the type adjust 180 degrees. An iPad is pretty, but it only has 60,000 titles, I can’t take it into my bathroom, and it doesn’t seem to be delivering the Curtis Sittenfeld’s latest. So it’s not that Amazon and the Atlantic got there first. They have always been here—figuring out how to deliver their authors to readers in every conceivable form. Looking at the cover of Fiction 2010 again, I might go so far as to say the real reason they’re the future of fiction and the iPad isn’t is that, unlike Apple, they both have a dog in this fight.

Bonus Links: On The Atlantic‘s Redesign, My Political Blog Hangover and the Virtues of Finitude