1.

1.

Edmund Wilson encouraged his second wife Mary McCarthy’s first forays into fiction by shutting her in a room for three hours and asking her to write a story. Author Shirley Jackson’s husband Stanley Hyman, a literary critic and writer for The New Yorker, devised strict writing schedules for her. And with the money from Jackson’s royalty checks, he purchased a dishwasher to make more time for her writing. Alice B. Tolkas tended to domestic duties so that her partner, Gertrude Stein, could pursue her literary endeavors. As Stein said, “It takes a lot of time to be a genius, you have to sit around and do so much nothing, really do nothing.”

Stein’s statement sounds like an exaggeration, but is it really? While most writers don’t have the dispensable time to become geniuses of Stein’s definition, writing requires a certain amount of intellectual autonomy. One common bond linking McCarthy, Jackson, and Stein—three women featured in Elaine Showalter’s history of American women writers, A Jury of Her Peers—is that their spouses allowed them the time and solitude required to imagine, write, and produce. Even if their spouses’ approaches were controlling or their motivations questionable, the writing flourished.

Showalter also profiles Catharine Maria Sedgwick, a popular writer from the early 1800s who never married. Sedgwick felt deeply ambivalent about remaining single, which is reflected in her story “Cacoethes Scribendi,” in which a group of four sisters, one married, take up writing as a hobby. The daughter who refuses to write seduces and marries the only eligible bachelor in town. With his proposal, Sedgwick writes, the girl’s mother and aunts “relinquished, without a sigh, the hope of ever seeing her an AUTHOR.” Sedgwick implies that marriage and writing are antithetical, and that a woman loses hope of becoming an author, and perhaps even remaining one, once she’s married.

Of a contemporaneous writer, Fanny Fern, Nathaniel Hawthorne critiqued:

The woman writes as if the Devil was in her and that is the only condition under which a woman ever writes anything worth reading. Generally women write like emasculated men, and are only to be distinguished from male authors by greater feebleness and folly; but when they throw off the restraints of decency and come before the public stark naked… then their books are sure to possess character and value.

While social mores have changed, books written by women about marriage and other domestic topics continue to crowd Hawthorne’s categories of “feebleness and folly,” and flourish. We need not look far for proof. Elizabeth Gilbert’s latest book, Committed, topped the New York Times Best Sellers list last week. The book’s narrative wrestles with the issue of whether or not Gilbert should remarry (she does). While some women writers and collections featuring their stories, such as This Is Not Chick Lit, attempt to thwart expectations of the usual modes of feminine domesticity and decency, they remain a minority. At least these women are no longer considered possessed.

While social mores have changed, books written by women about marriage and other domestic topics continue to crowd Hawthorne’s categories of “feebleness and folly,” and flourish. We need not look far for proof. Elizabeth Gilbert’s latest book, Committed, topped the New York Times Best Sellers list last week. The book’s narrative wrestles with the issue of whether or not Gilbert should remarry (she does). While some women writers and collections featuring their stories, such as This Is Not Chick Lit, attempt to thwart expectations of the usual modes of feminine domesticity and decency, they remain a minority. At least these women are no longer considered possessed.

Likewise, the anxiety of maintaining the distance and time to write within a romantic relationship continues to plague women (and men alike). Henry James’s “The Lesson of the Master” touches on this conundrum from the male perspective. In James’s story, the fledgling writer Paul Overt takes advice from the esteemed “master,” Henry St. George, and chooses his writing over pursuing a potential paramour. Overt travels abroad and pens a well-regarded novel, but returns home to find that the happy and unproductive St. George nabbed his girl. Overt wonders if he made the right choice by following intellectual passion instead of romance. Or if he really needed to make a choice at all.

2.

Speaking of romantic choices, at HTMLGiant Nick Antosca recently posted a provocative list of reasons why writers should not date writers. He claimed that writers are less likely to let their significant others use writing as an excuse to avoid social obligations. But I’m wondering if he’s wrong, and that writers should date writers, who will likely understand the importance of clearing time and mental space to write. In spite of the control McCarthy’s and Jackson’s husbands exerted, their marriages show that liaisons with other writers can help make the space to write within the constraints a relationship. What matters most, it seems, is the agreed upon arrangement.

Katie Roiphe (of recent note for her New York Times essay about the sad state of male sex writing, which Sonya responded to here) wrote about unconventional couplings in her book, Uncommon Arrangements, which profiles seven unusual marriages in Britain between 1910 and World War II. Roiphe calls them “marriages à la mode” (a name she borrowed from a Katherine Mansfield story) to underscore the ways these couples, triads, and more complex entanglements sought imaginative, and at times almost untenable, set-ups to fulfill their needs and romantic desires.

Katie Roiphe (of recent note for her New York Times essay about the sad state of male sex writing, which Sonya responded to here) wrote about unconventional couplings in her book, Uncommon Arrangements, which profiles seven unusual marriages in Britain between 1910 and World War II. Roiphe calls them “marriages à la mode” (a name she borrowed from a Katherine Mansfield story) to underscore the ways these couples, triads, and more complex entanglements sought imaginative, and at times almost untenable, set-ups to fulfill their needs and romantic desires.

These arrangements didn’t provide equal satisfaction for everyone involved, but for the writers who flourished a few common foundations aided their craft. Having money helped matters, of course. The young journalist and novelist Rebecca West was seduced by the older, established, and very married H.G. Wells, who fathered her child. He provided a house for West and their son, but he also chose to stay with his wife. This may have been a wise decision on Wells’s part—because it also helps as a writer to have a wife. By wife, I mean a partner who tends to the cleaning and cooking, watches the children and oversees the social affairs. Gender doesn’t matter, although in these cases a woman always occupied the role. An extremely devoted friend also suffices.

Take Katherine Mansfield as an example. Her on-again, off-again and highly impractical romance with the writer and editor John Middleton Murry developed out of a sense of mutual respect but offered little stability. When Mansfield contracted tuberculosis and had to spend winters abroad due to her health, Murry remained at home in England. Instead, Mansfield’s friend Ida Baker accompanied her, cared for her, and even woke to toast her in the middle of the night when she completed a story. These were some of Mansfield’s most productive years.

Retaining separate residences, a room of one’s own if you will, also provides space for lovers to write. The writer Vera Brittain married the academic George Catlin, who offered her “as free a marriage as it lies in the power of a man to offer a woman.” When he found a teaching position at Cornell, she moved with him across the Atlantic, but after the first year she returned to England and stayed. Roiphe writes: “It was [Vera’s] elaborately articulated position that a woman must be productive, and if that productivity was compromised by her domestic arrangements she had an obligation to change them.” And so Vera enlisted her dear friend Winifred Holtby as a third party in their marriage. Winifred would share the London residence, the expenses, and travel as she liked. She was Vera’s housemate and back-up nurse. Mary Wollstonecraft’s unlikely marriage to William Godwin (unlikely in that both opposed matrimony in their writing) never resulted in cohabitation. According to Cristina Nehring’s account of their romance in Vindication of Love, Wollstonecraft and Godwin kept separate flats, twenty doors apart, and sent notes to each other via a messenger.

Retaining separate residences, a room of one’s own if you will, also provides space for lovers to write. The writer Vera Brittain married the academic George Catlin, who offered her “as free a marriage as it lies in the power of a man to offer a woman.” When he found a teaching position at Cornell, she moved with him across the Atlantic, but after the first year she returned to England and stayed. Roiphe writes: “It was [Vera’s] elaborately articulated position that a woman must be productive, and if that productivity was compromised by her domestic arrangements she had an obligation to change them.” And so Vera enlisted her dear friend Winifred Holtby as a third party in their marriage. Winifred would share the London residence, the expenses, and travel as she liked. She was Vera’s housemate and back-up nurse. Mary Wollstonecraft’s unlikely marriage to William Godwin (unlikely in that both opposed matrimony in their writing) never resulted in cohabitation. According to Cristina Nehring’s account of their romance in Vindication of Love, Wollstonecraft and Godwin kept separate flats, twenty doors apart, and sent notes to each other via a messenger.

3.

In contrast to these rather dated romances, Chris Kraus’s epistolary novel I Love Dick depicts an even more ostentatious arrangement between a husband and wife named Chris Kraus and Sylvère Lotringer, the Columbia professor, editor, and philosopher who is also Kraus’s real-life husband. As Chris’s infatuation with her husband’s colleague Dick develops into an all-consuming obsession, Chris devises ways to seduce him. She talks candidly with Sylvère about her obsession in hyperbolic exchanges reminiscent of those shared by teenage girls.

In contrast to these rather dated romances, Chris Kraus’s epistolary novel I Love Dick depicts an even more ostentatious arrangement between a husband and wife named Chris Kraus and Sylvère Lotringer, the Columbia professor, editor, and philosopher who is also Kraus’s real-life husband. As Chris’s infatuation with her husband’s colleague Dick develops into an all-consuming obsession, Chris devises ways to seduce him. She talks candidly with Sylvère about her obsession in hyperbolic exchanges reminiscent of those shared by teenage girls.

Chris and Sylvère are no longer having sex, but the external charge Dick supplies reignites their passion, at least temporarily, as husband and wife start collaborating, by writing love letters to Dick on Chris’s behalf. Sylvère makes phone calls; he imagines he’s Charles Bovary to Chris’s Emma. Chris continues to write, passionately and desperately. She turns her love-induced graphomania into performance art, and then into an epistolary novel. We as readers are led to believe that the letters she wrote to Dick, in turn, form the foundation of this book. For Kraus, love wasn’t just inspiration, it was art, it was all.

Chris’s obsession with Dick is central to the novel, but he also remains removed. Her husband, in turn, provides encouragement, companionship, and, surprisingly, acts as a collaborative accompanist within her fantasy.

If I Love Dick portrays a contemporary marriage à la mode, it also reflects the ways that the feminine role has changed—and resisted change as well. Kraus admits that in spite of her husband’s renown in the art world, at the time she wrote the book, no one took her seriously. Her anonymity gave her freedom to take risks.

Falling in love didn’t stunt Kraus’s writing. It inspired her. She said in an interview, “when you fall in love with someone the greatest rush is that you can be so many more sides of yourself with them than with anyone else in the world.” Dick’s distance allowed her to imagine, to fantasize, to write her fantasy into existence. Kraus has certainly thrown off the restraints of decency, and of privacy. No doubt, Hawthorne would pay her the compliment.

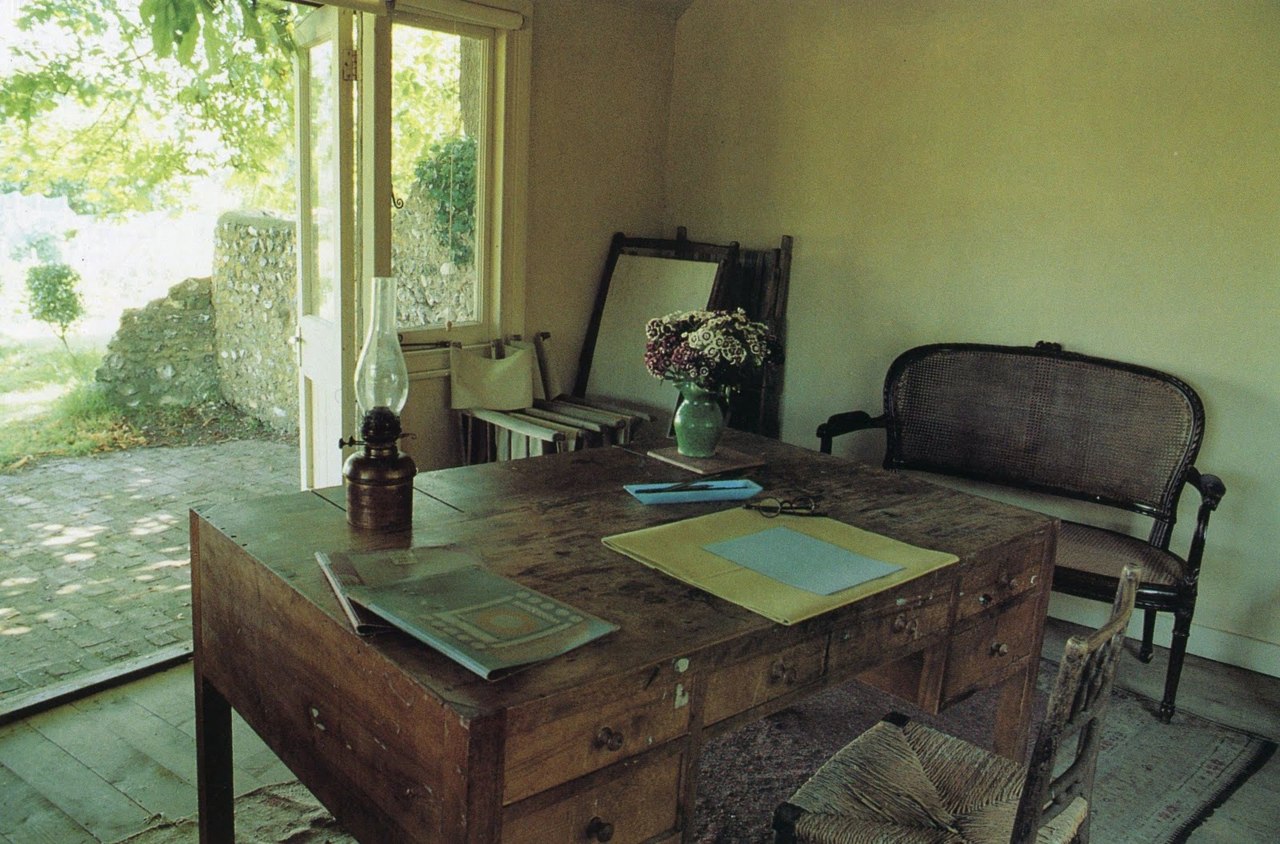

[Image: Virginia Woolf’s writing desk in her study in Rodmell, England.]