1.

1.

I’m not a gamer, in any conventional sense. I like Brickbreaker, that insanely addictive game that seems to come standard on the Blackberry, and I can lose myself for twenty minutes or so in Tetris, especially if I’m on an airplane, but that’s about the extent of it. There are games that I’ve sometimes been tempted to play because I’ve heard that their worlds are beautiful, but I’ve resisted on the grounds that the absolute last thing I need is an absorbing beautiful thing to lose time in.

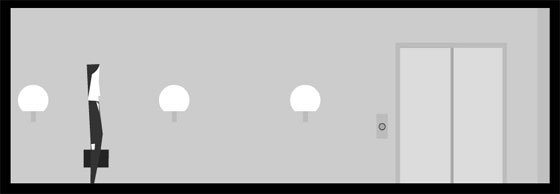

Given all this, I was surprised by how thoroughly I fell for Molleindustria’s Every Day The Same Dream when I encountered it a month or so ago. It’s a strange, somewhat harrowing little game that you play in your web browser, beautiful in the bleakest possible way. The world of the game is grey, constrained, populated by ghosts. The set-up is simple: your avatar gets up every morning and goes to work. Except that it isn’t quite every morning; after one or two rounds, you realize that your avatar’s caught in a repeating dream. And the thing is, chances are you’ve been here before: if you’ve ever felt trapped in a job that you hated, if you know what it’s like to get up every morning and set out into a pale workday that far too closely resembles yesterday and the day before and the day before that, then you may find this world suffused with a chilly familiarity. I did.

The game begins with your avatar standing next to his bed. The graphics are simple: he’s a white undifferentiated silhouette of a man. You walk him to the wardrobe and he puts on a suit. He walks past his wife, who’s perpetually cooking breakfast; she tells him that he’s running late. He walks down the corridor, descends in the elevator, gets in his car, drives to work, is yelled at by his silhouette boss, and walks down an endless line of cubicles populated by silhouette men who look exactly like him, until he finds a cubicle that’s empty. When he sits down in the empty cubicle the game begins again; he’s standing in his boxers by his bed.

The point of the game seems to be to break this numbing routine. Options and variations begin to reveal themselves: you can decline to put on your suit and then get fired for showing up at work in your underwear. Instead of getting in your car you can walk in the opposite direction to a desolate intersection, where just once in the game you’ll encounter a robed and hooded homeless man. “I can take you to a quiet place,” he tells you, and then he takes you to a graveyard where you linger for just a moment before you wake up standing by the bed again. You can get out of your car on the freeway, walk into a field and pet a cow. You can catch an orange leaf as it falls from a monochrome tree outside your office. You can walk past the endless row of cubicles onto a rooftop, and throw yourself over the edge.

Several commentators on various online forums devoted to gaming describe it as “a creepy little game.” I can’t really disagree, but it’s also beautiful.

2.

The game was created two months ago by Molleindustria, which describes itself as “an Italian team of artists, designers and programmers that aims at starting a serious discussion about social and political implications of videogames.” Molleindustria was founded by Paolo Pedercini, born “somewhere in northern Italy” in 1981. He describes Every Day The Same Dream as “a slightly existential riff on the theme of alienation and refusal of labor.”

One can spend hours trying to decipher the meaning of the game (and people have, endlessly, in the afore-mentioned gaming forums.) But meaning aside, and even aside from the sad beauty of the game’s gray world, I was thinking about it the other day and I realized part of its appeal: it reminds me, in its very existence, of what the Internet used to be.

3.

I came online in the mid-90s. People were pouring online in those days, but not everyone was there yet; I was far enough over on the leading edge of the curve that my classmates at The School of Toronto Dance Theatre thought I was exotic for having a computer and an email address, but far enough behind that astonishing things had already been done. The artistic potential of the Web had become apparent over the previous several years, and some of the websites I encountered were absolutely beautiful. I began teaching myself HTML code in my bedroom at night.

In those days you could create unbelievably ugly websites with HTML editing programs, but generally speaking, an online presence required a working knowledge of HTML, some manner of graphics editing software, and ideally at least a passing familiarity with Javascript. We didn’t have blogs, we had personal websites; all of them were unique, because there were no templates to follow, and some of them were gorgeous.

“The web is still artistically driven by unaffiliated labors of love,” the website designer Paul Frost wrote, sometime during that period.

I’m sometimes nostalgic for what the web was back then. I don’t claim that it was better. It was just different. There were high barriers for entry, and it wasn’t nearly as useful: aspects of the web that I take for granted today (buying groceries online, booking plane tickets, etc.) weren’t really there yet. But at the same time it was a stranger, wilder, in some ways more beautiful place.

Every Day The Same Dream reminds me of that lost web. It’s nothing if not an unaffiliated labor of love.